A coup by a group of special forces from the Guinean military on Sunday 5 September has brought to an end a period of political stability dating back to President Alpha Condé’s election in 2010.

The coup organisers, headed by Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, cited alleged mismanagement of the economy, corruption and disregard for democratic principles and human rights as the reasons for overthrowing the government. The newly formed transitional authority (CNRD) has already announced that it will proceed to rescind the 2020 Constitution, promising a new national charter within an unspecified timeframe. Meanwhile, the president, all government ministers and all local government officials have been removed from office.

The CNRD held meetings at the presidential palace on 6 September to help organise the transition, demanding that members of the outgoing government attend. The exact contents of these meetings are likely to remain unclear until the CNRD announces its blueprint for the new government in the coming days, but in a public speech at the palace they implored mine operators to continue operations and confirmed that maritime borders had been reopened. The CNRD’s policy direction remains a black box, and the fate of the Simandou iron ore deposits is now more uncertain.

Surprise coup could have ripple effect

Despite claims by members of the opposition that this coup was predictable, there were few signs of instability in the country’s military in the months leading up to the event. The last coup occurred in 2008, and there have been only negligible hints of mutinous sentiment within the military since. The most notable recent event was in March 2020, when two military officers exchanged gunfire in the Alpha Yaya Diallo military base in Conakry, but this did not stem from anti-government motives.

However, our data shows that the conditions were in fact ripe for a coup. Guinea ranked joint 7th globally on our State Instability Index in 2021-Q3, which forecasts the risk of a country experiencing the onset of a major destabilising event, such as a civil war, adverse regime change, or genocide/politicide.

While recent events in Guinea will certainly damage the country’s own prospects for political stability, there is a danger that the coup – the third in Francophone Africa in 2021 – causes a ripple effect across West Africa, especially for governments with disputed legitimacy. We expect these events to embolden military officers in countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Cameroon, Togo and Gabon, where governments have staved off major opposition movements, coup attempts and army mutinies in recent years.

Find out more about our Country Risk Intelligence service

Fate of Simandou remains unclear

While it seemed likely initially that bauxite supply would be disrupted, the CNRD’s decision to reopen maritime borders and encourage miners to resume operations will contain much of the early uncertainty regarding a potential suspension to exports. However, poor communication by the new authority spooked the market: aluminium future prices have increased over 1% since Sunday, highlighting the importance of Guinea’s bauxite supply to global markets.

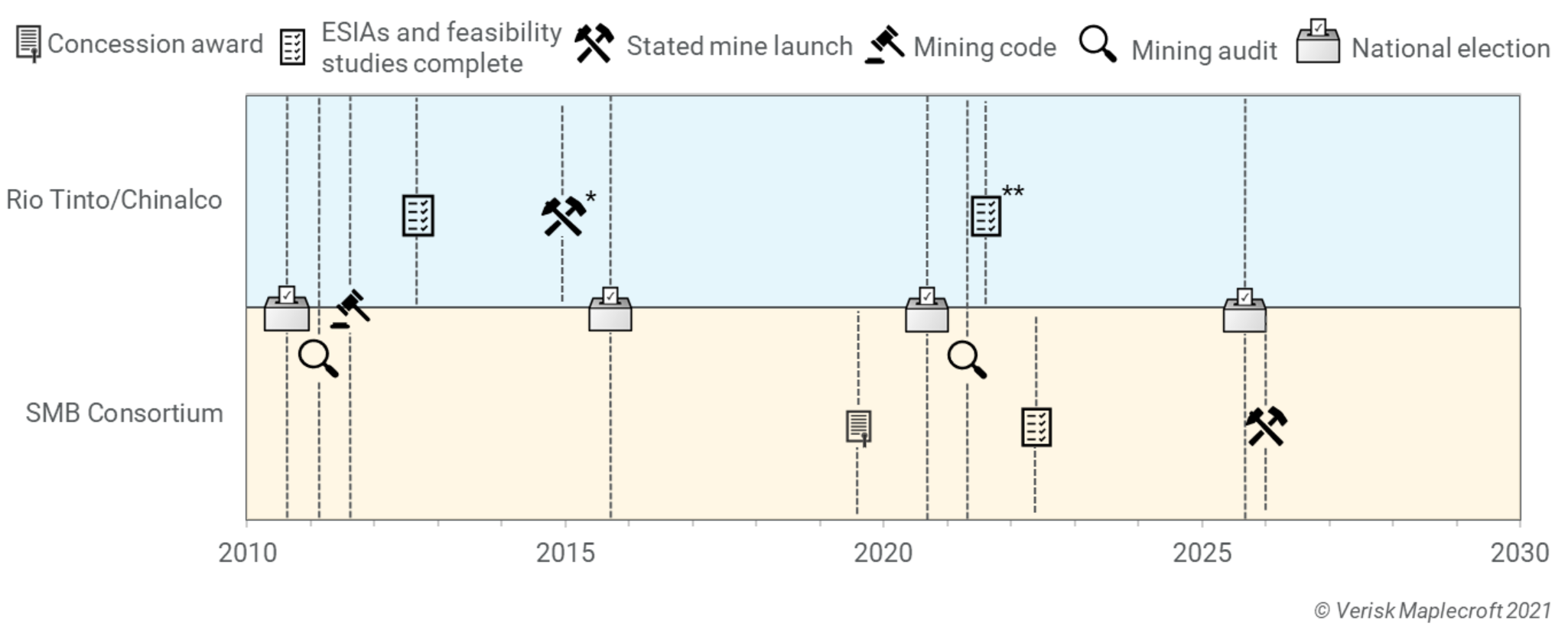

In terms of development of the Simandou iron ore deposits, we anticipate delays to stated project timelines (see below). The Winning Consortium Simandou (WCS) vehicle set up by the SMB consortium has publicly announced its intentions to deliver its feasibility study for the integrated rail-port-mine project by December 2021, but the deadline is likely to slip after the shake-up across all levels of government.

So far, the CNRD has given no indication as to its intentions for the country’s mining policy. In the main, opposition leaders have historically supported the development of the trans-Guinean railway as a means to export iron ore from Simandou, but there is no guarantee that a government of national unity will not make additional stipulations. A review of the mining fiscal framework cannot be discounted, as Guinea’s 2011 Mining Code remains among the most competitive in the region.

Uncertain outlook for mining contracts

There is a remote risk that the soon-to-be announced government of national unity will seek to renegotiate existing mining contracts or expropriate foreign-owned mine assets. It remains most likely that miners will be able to continue operating, even though we lack clarity on the direction of the country’s mining policy and who will manage the government’s portfolio. The full makeup of the interim government will likely be clearer by 10 September.

The SMB consortium’s privileged relationship with the Guinean authorities – which was rooted in strong personal ties to President Condé – will certainly be weakened by the change in government. However, the consortium has in its favour a strong track record of development in the country's bauxite sector, which we expect will make it a less likely target for any potential contract renegotiation or expropriation.

Riskier prospects for government stability

There is still no timeline for developing the new constitution or indeed holding general elections. The dissolution of all levels of government has centralised decision-making in the capital Conakry, which will require operators to factor in additional time buffers for administrative processes. Although the CNRD has begun to put military commanders in charge of the country’s various prefectures, we expect them lack the wherewithal to respond to local grievances beyond maintaining security.

There appears to be some sympathy between the CNRD and the opposition FNDC movement, which was established to contest President Condé’s controversial third-term bid. The CNRD has already announced that it will release several detained FNDC protestors, for instance. It is also revealing that not a single opposition leader has publicly condemned the coup, indicating that relations between those and President Condé’s wider RPG-Arc-en-Ciel political grouping are likely to remain tense.