Throughout 2023, we've been diving into our suite of 170+ country risk indices to highlight the myriad interconnected risks that companies are having to contend with, from economic turmoil and mounting political instability, to an increasingly complex human rights landscape and the impacts of the evolving climate crisis.

So far this year, the war in Ukraine, intensifying great-power competition and the residual impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic have been the three major themes underpinning the global risk environment. But with hostilities now escalating in the Middle East, it is clear the world is in an extended period of heightened volatility.

As such, it is more important than ever for companies to monitor and anticipate the risks impacting the resilience of their operations, supply chains and investments. In this article, we’ve used our latest data to highlight some of the major shifts and developments to watch in the global risk environment, from political instability in the Middle East to rising human rights risks in North America.

Conflict upends MENA’s shift towards greater stability

Data from our Conflict Intensity Index, which last updated prior to the escalation of hostilities in Gaza, shows that the Middle East saw a reduction in armed conflict between 2018-Q1 and 2023-Q4. This was driven by a significant reduction of risk in several countries, including Iraq, Libya, Egypt and Yemen.

Israel and Palestine were the notable exception. Indeed, Palestine was the only country in MENA that saw an increase in risk on the index, falling from 14th to 3rd highest risk globally (where 1st is the worst performing country), behind only Syria and Burkina Faso. Despite its score remaining static, Israel fell to 6th highest risk globally, down from 14th in 2018.

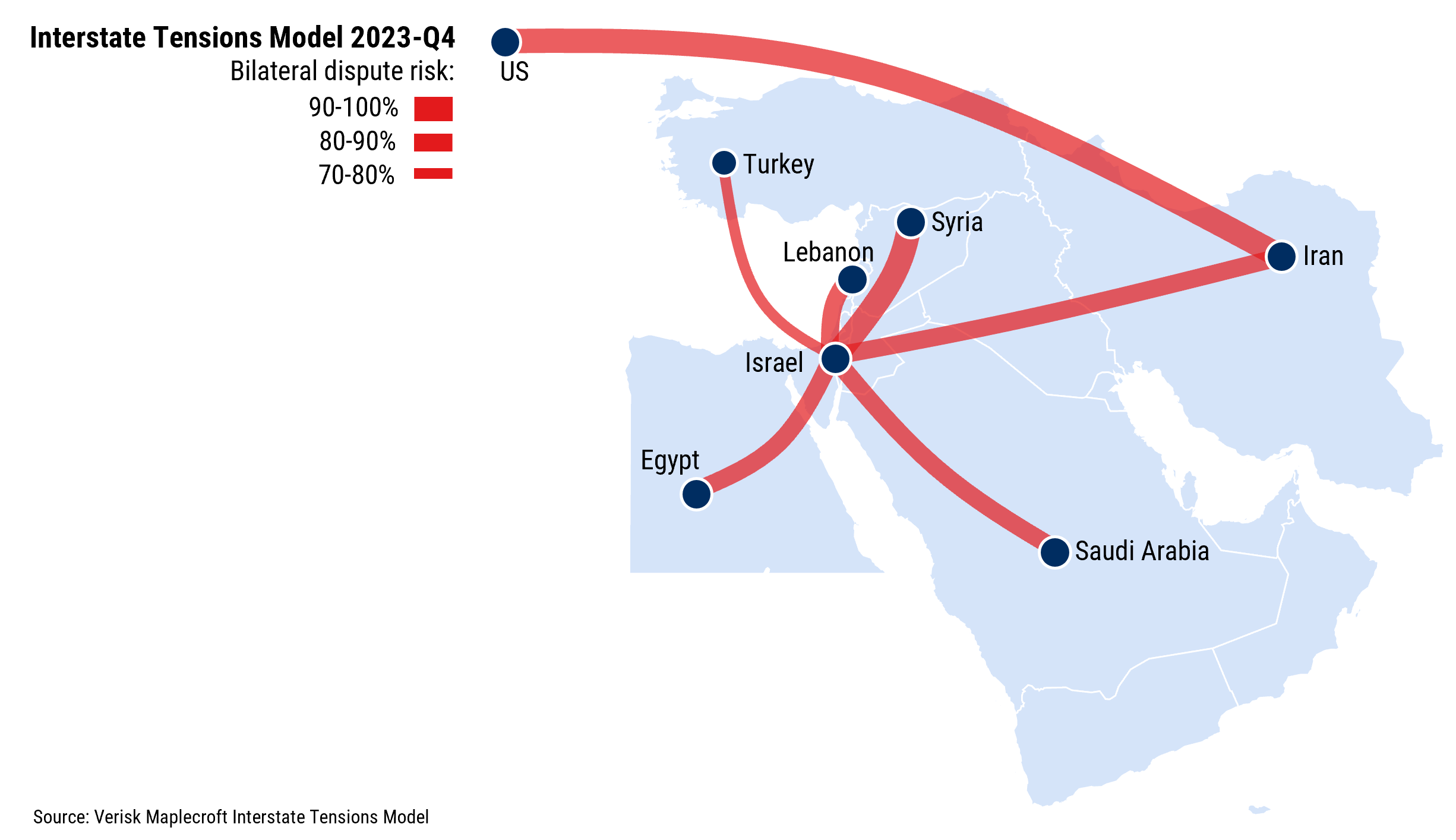

The current bout of hostilities in Israel and Gaza could threaten to reverse the decline in conflict across the region. Data from our Interstate Tensions Model (ITM), which measures the risk of a militarised dispute – including the threat, display, or use of force – between two countries, shows that there are several bilateral fissures that could open up over the next 12 months.

These include the pairings of Israel-Iran and Iran-US, both of which are considered more than 80% likely to engage in a militarised dispute in the next year, according to the ITM.

These tensions are already weighing on the region’s economic landscape. "In North Africa, government borrowing costs are set to increase amid rising political risk premiums. Additionally, higher oil prices threaten to stoke greater inflation and socio-economic unrest," says Senior MENA Analyst Torbjorn Soltvedt.

"Although the Gulf states remain relatively insulated from the war in Israel and Gaza, heightened geopolitical tensions come at a bad time as governments across the region seek to double-down on efforts to attract foreign direct investment."

MENA no longer isolated from global uptick in civil unrest

Even before the outbreak of the conflict, there were signs that MENA's political risk outlook was starting to sour.

Research conducted in September as part of the launch of our new SRCC (strikes, riots and civil commotion) Predictive Model – which provides 12-month forecasts on the risk of damaging bouts of unrest that result in insured losses – found that MENA was the only region globally that hadn’t seen an uptick in risk over the past two years. But the latest data shows that this is no longer the case, driven by significant increases in risk in key jurisdictions like Egypt and Turkey.

Figure 2: SRCC risks increased sharply in Egypt and Turkey this quarter

Egypt registered the sharpest increase in risk seen by any country on the SRCC model this quarter - falling 61 positions in the rankings to 41st highest risk globally. This is partly a result of the high rate of inflation in the country, which is widening inequalities as the country grapples with mounting economic distress.

The outbreak of hostilities in Gaza threatens to exacerbate these risks. The Egyptian government fears that protests sparked by the conflict could turn into more generalised demonstrations against the government itself, particularly if Cairo’s diplomatic position on the conflict is considered too weak.

It is a similar story in Turkey, where stubbornly high inflation has contributed to the country falling 24 positions in the rankings, down to 22nd highest risk globally. Major post-election hikes to interest rates by the Turkish central bank, intended to tackle inflation, will take time to filter through the economy, and in the meantime could stoke public discontent.

At the same time, Turkey has already seen several large-scale protests related to the Israel-Palestine conflict in its major cities, including in both Ankara and Istanbul.

Modern slavery risks increase in Canada, US

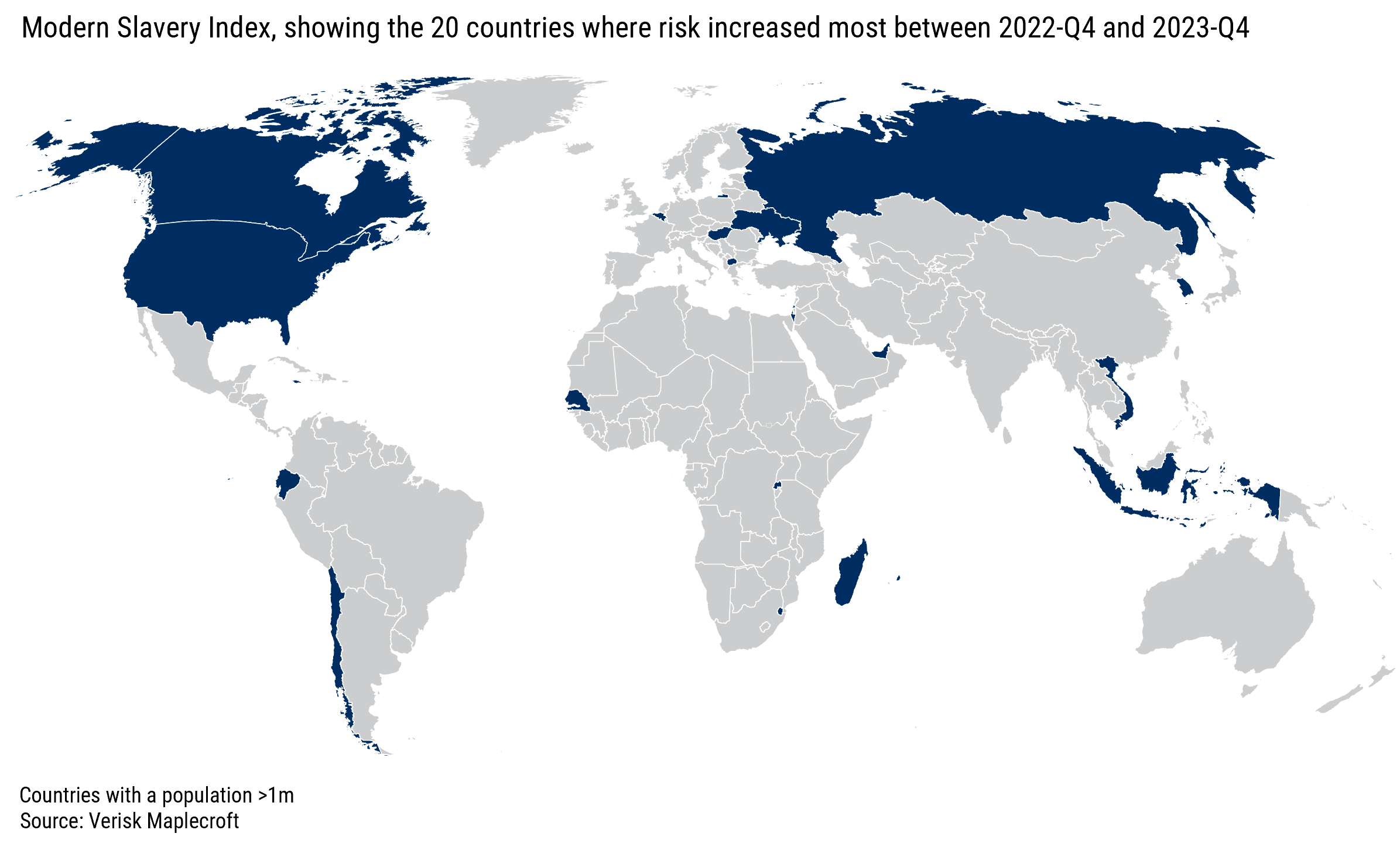

Looking beyond MENA and pivoting onto our human rights data, we’ve revisited our Modern Slavery Index (MSI) to see how the trajectory of risk played out over the past year.

In 2022-Q4, we found that 51 countries had seen a significant increase in risk since 2016. A further 28 countries have seen their score significantly worsen since then, compared to 26 that registered a significant improvement.

While risks continue to run highest in the developing world, the data shows that the issue is worsening in several major economies. These include Canada and the US, as well as key emerging markets like Indonesia and Vietnam.

Indeed, Canada has slipped into the medium risk category of the index, having been rated low risk since 2017. It now ranks as the 159th highest risk country globally, down from 172nd in 2022-Q4.

The indicators underpinning the MSI show that this has been driven by a decrease in the effectiveness of law enforcement in tackling forced labour. Other drivers include the expansion of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP), a visa scheme recently branded by the UN as a ‘breeding ground’ for contemporary forms of slavery.

Some 200,000 migrants entered Canada under the TFWP in 2022, up nearly 70% from 2021. According to the UN, migrant workers who enter Canada under the TFWP are particularly vulnerable to exploitation, as they cannot report abuses without fear of deportation.

"A hardening of political rhetoric and policy towards migrant workers has been observed in many parts of the Global North," notes Dr James Sinclair, our Director of Human Rights. "As a consequence, people who are already vulnerable to exploitation and abuse are often finding themselves further marginalised, and often have inadequate means of redress."

Meanwhile, the US (rated medium risk on the index) fell 17 positions in the rankings to 130th highest risk. Our data shows that this has primarily been driven by an uptick in the frequency of forced labour violations. These often involve undocumented workers, many of whom have crossed into the US as part of the ongoing border crisis.

Once in the US these migrants can be vulnerable to exploitation; particularly in agriculture, where undocumented workers make up half of the labour force. US agriculture is rated high risk for modern slavery in our Industry Risk Analytics dataset and is the country's worst performing sector.

Outside of North America, Vietnam and Indonesia - two increasingly important players in global supply chains as companies look to 'nearshore' their activities amid escalating great-power competition - have fallen to 15th and 30th highest risk respectively, down from 22nd and 55th.

Reports by the US State Department found that despite efforts to eliminate trafficking, both the Vietnamese and Indonesian governments have failed to proactively identify victims in sectors such as fishing and in the informal economy. Vietnam sits within the very high risk category of the MSI, with Indonesia rated high risk.

Cutting-edge analytics key to business resilience

The list of issues unpacked above is far from extensive. As volatility continues to impact the global risk environment in the months ahead, businesses that embed geospatial risk data as a key pillar of their risk management processes will stand the best chance of anticipating where uncertainty could crystalise into hardening risk.