Sovereign sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) have so far been extremely rare, with Chile and Uruguay the only issuers to date. However, this may soon change. South Africa, Thailand, Kenya and Rwanda have recently floated the prospect of issuing some this year. Emerging market governments are starting to take notice of SLBs’ flexibility and potential for accessing a deeper pool of international finance, especially to finance the energy transition. Unlike green or sustainability bonds, SLBs do not impose use-of-proceeds requirements on the issuer. Instead, they oblige it to achieve predetermined key performance indicators (KPIs) to avoid a step up in coupon payments (or, as in the case of Uruguay, benefit from a step down).

But there are good reasons for investors to be wary about SLBs’ potential for meaningful impact, and hence their credibility. Questions of materiality and additionality loom large. It may not be clear whether KPIs would be achieved anyway without any additional effort. There can be a mismatch of timescales: a KPI may relate to a long-term structural trend which the issuing government has limited power to affect in the time available to meet a short-term target. Nor are coupon step-ups hefty enough to incentivise progress. In practice, SLB penalties are typically very low (12-25bps), usually less significant than global interest rate moves. This renders the instrument more of a signalling device – a show of intention on the part of the government and of support on the part of the investor – that marks a direction of travel rather than a promised final destination.

And there are broader challenges too. Binding successors to stringent and potentially uncosted KPIs and their associated debt could prove controversial and be considered anti-democratic, while failure to achieve KPI targets may impact market credibility. Ensuring that the contracting government enjoys political legitimacy, that the overall governance process is robust and that there is broad-based consensus about the need for the underlying objectives all need to feature in investors’ due diligence. Achieving buy-in across disparate ministries and government agencies is no small feat and is likely to be a major impediment to SLB issuance for many nations.

An ideal world: potential KPIs for sovereign SLB issuers

Agreeing on the right KPIs is absolutely paramount for investors and issuers. So, if and when South Africa, Rwanda, Kenya and Thailand do come to market with new sovereign SLBs, what areas should their KPIs be targeting? As per the Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles, KPIs are expected to be relevant, core, material, measurable and quantifiable, externally verifiable and benchmarked against relevant external references. Most of all, they should also be focused on areas where policy and investment can be directed to generate better outcomes. Potential KPIs run across a broad range of environmental and social themes, from GHG emissions and energy consumption, through to biodiversity, air quality, recycling, sustainability of fish stocks, diversity and inclusion, educational completion rates or digital inclusion. This is where our data can be used to identify appropriate themes for investors to engage on.

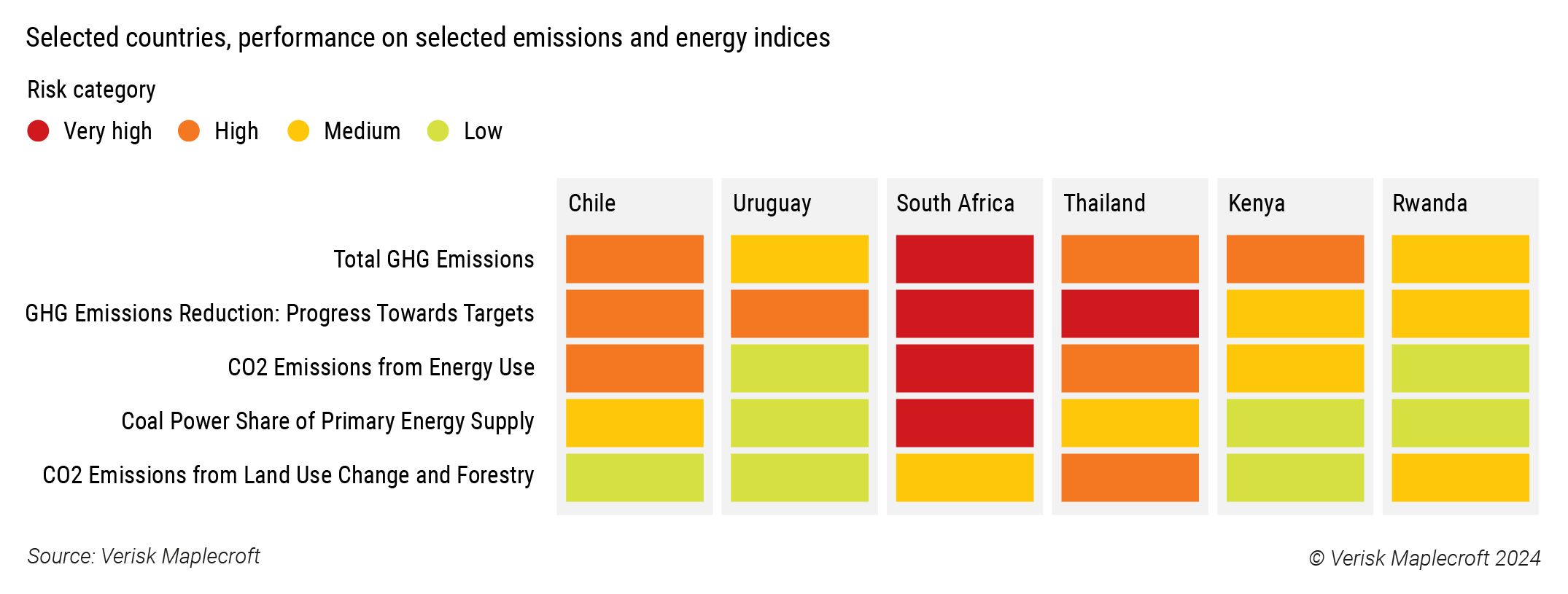

Energy transition and emissions reduction strategies will obviously feature heavily across the board, given the urgency and scale of the task and the investments required, as well as the willingness of investors to channel financing to this end. All four prospective issuers are likely to include an emissions KPI, as did Uruguay, a relatively low emitter (see Figure 1). South Africa, where the energy transition is both urgent and overwhelming, is likely to concentrate its efforts wholly on climate and transition. According to our data which highlight South Africa’s poor performance on Coal Power Share of Primary Energy Supply, CO2 Emissions from Energy Use, and Total GHG Emissions (585 MTCO2e), reducing emissions will probably be a key area of focus.

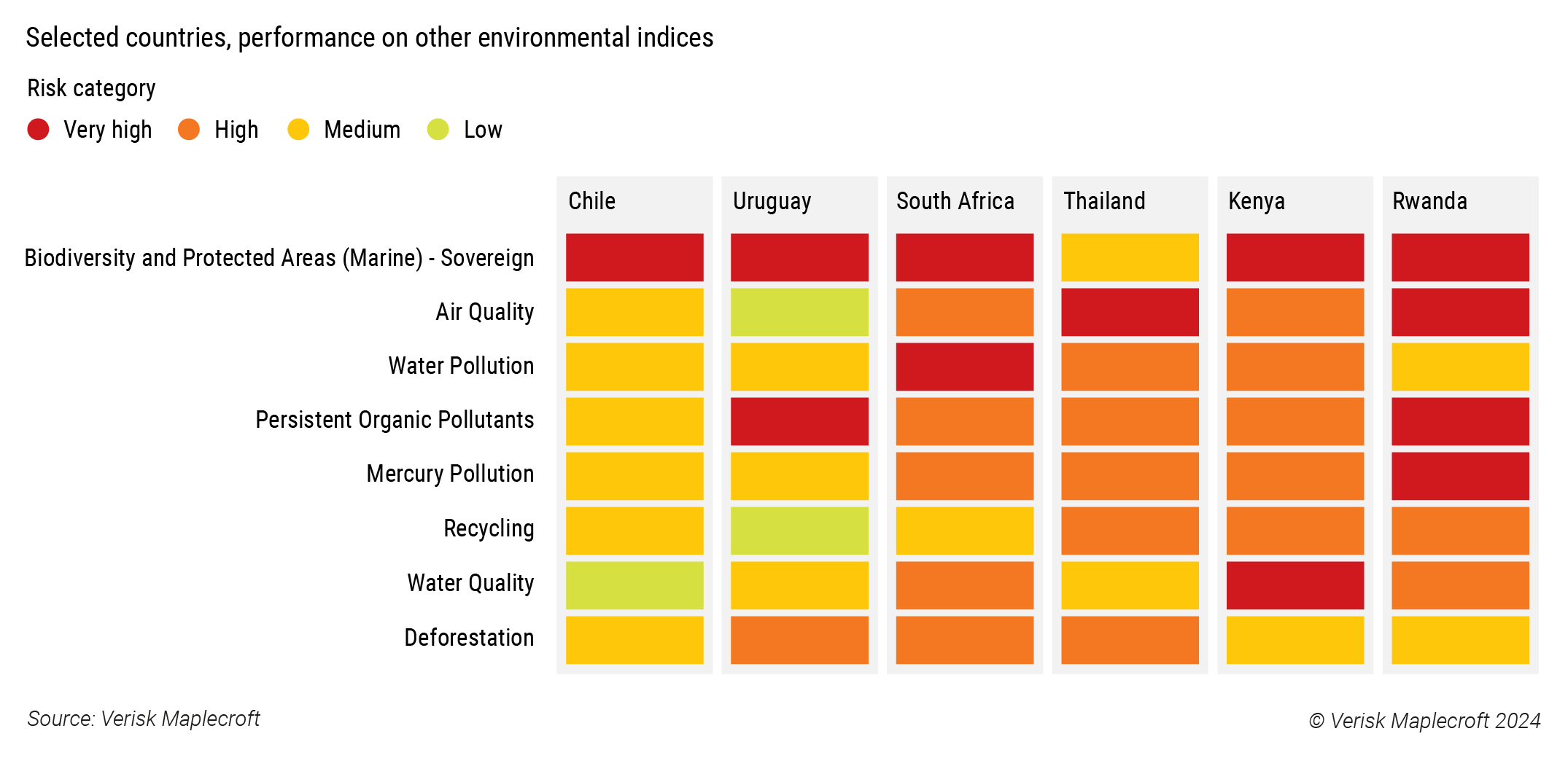

However, our data suggest there are plenty of other pressing environmental challenges that these issuers can focus on. In Thailand, improvements in air quality are a priority area. In Kenya, where drought is a recurrent threat, KPIs could target improvements in water quality and water pollution. In Rwanda, the focus could be more on reducing all forms of pollution: the country registers as very high risk on our Air Quality, Persistent Organic Pollutants and Mercury Pollution indices. Additionally, all these countries could benefit from targeted investment to tackle deforestation.

As ever, data will be key to identifying country performance and progress on key issues.

Human rights: handle with care

Investors working on SLBs need to approach human rights with caution. Constructive conversations with issuers, otherwise happy to move ahead with environmental initiatives, may be difficult or impossible. Moreover, investors should not be in a position to grant pecuniary rewards for compliance with treaties or national laws they are supposed to be adhering to anyway, nor to benefit from a stepped-up payout in the event that desired human rights outcomes are not achieved.

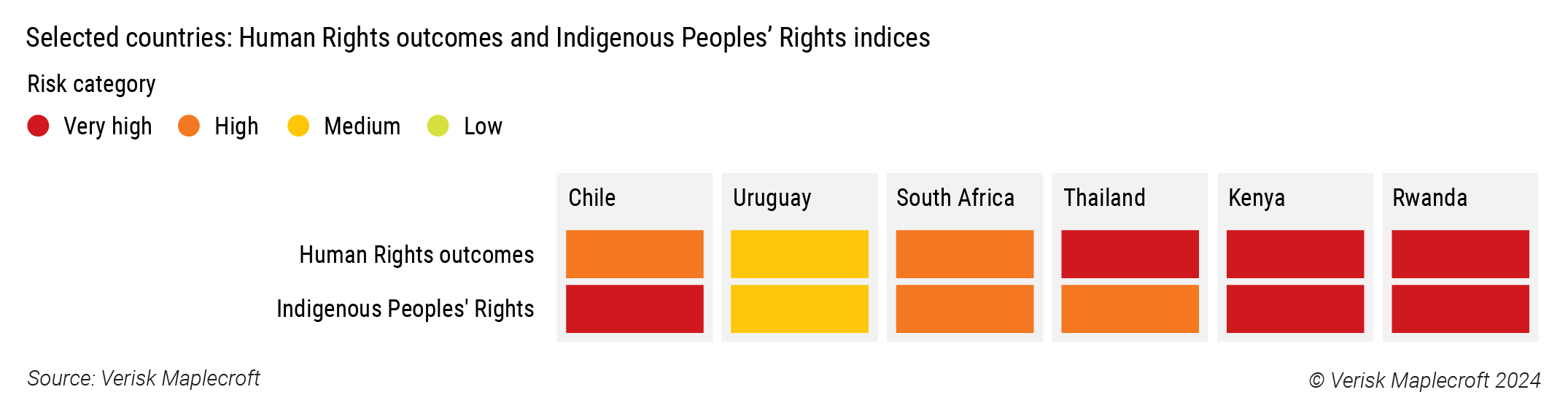

Nevertheless, such considerations might still have a place in the process – an assessment of progress might be considered as a complement to the servicing of the bond. Our data suggests that investors with an ESG remit are likely to support a focus on human rights outcomes if a mechanism could be agreed.

In our index averaging out all the outcomes metrics across our human rights indices used for SFDR reporting, South Africa falls into the high risk category while Kenya, Rwanda and Thailand are all classed as very high risk. For their part, Chile and Uruguay both perform better across human rights indices with the exception of Chile’s very high risk score for Indigenous Peoples’ Rights. But Chile’s recently announced second KPI, a target for 40% of female representation on boards by 2031 (replacing the original renewable energy generation target) is a more serviceable example of a quantifiable and verifiable goal, albeit one that has proven challenging to implement.

Moving ahead

Governments’ growing interest in the sovereign SLB financing structure is a function of its apparent flexibility and simplicity. However, as with all public debt instruments, implementation comes with considerable practical and political challenges. All four countries reportedly considering issuance this year have the scope to establish meaningful KPIs associated with GHG emissions reduction plus broader environmental objectives – ideally with an additional commitment to social progress. Investors looking to participate will first and foremost want to use data to identify appropriate KPIs. They will also need to fully inform themselves about whether there is broad political consensus for the KPIs and that there are strong governance procedures in place – particularly given the current absence of agreed international standards or any external validation mechanism.