As 2025 gets underway in earnest, responsible investors must grapple with turmoil both in the sustainable finance industry itself and in the wider economic, geopolitical, regulatory and sustainability risk environment. Here our Sustainable Finance team identify some of the key issues to watch this year.

1. Sustainable finance: down but not out

The ESG backlash has firmly taken hold. In the US, the new administration is withdrawing from the Paris Agreement and unwinding Biden-era green industrial policies. States and federal lawmakers have continued with anti-ESG ‘lawfare’ and major banks have fled net-zero coalitions. On the other side of the Atlantic, investor and corporate sustainability regulations are up for review after last year’s rightward shift in European parliamentary elections. But will the U-turn on environmental, social and governance issues intensify further?

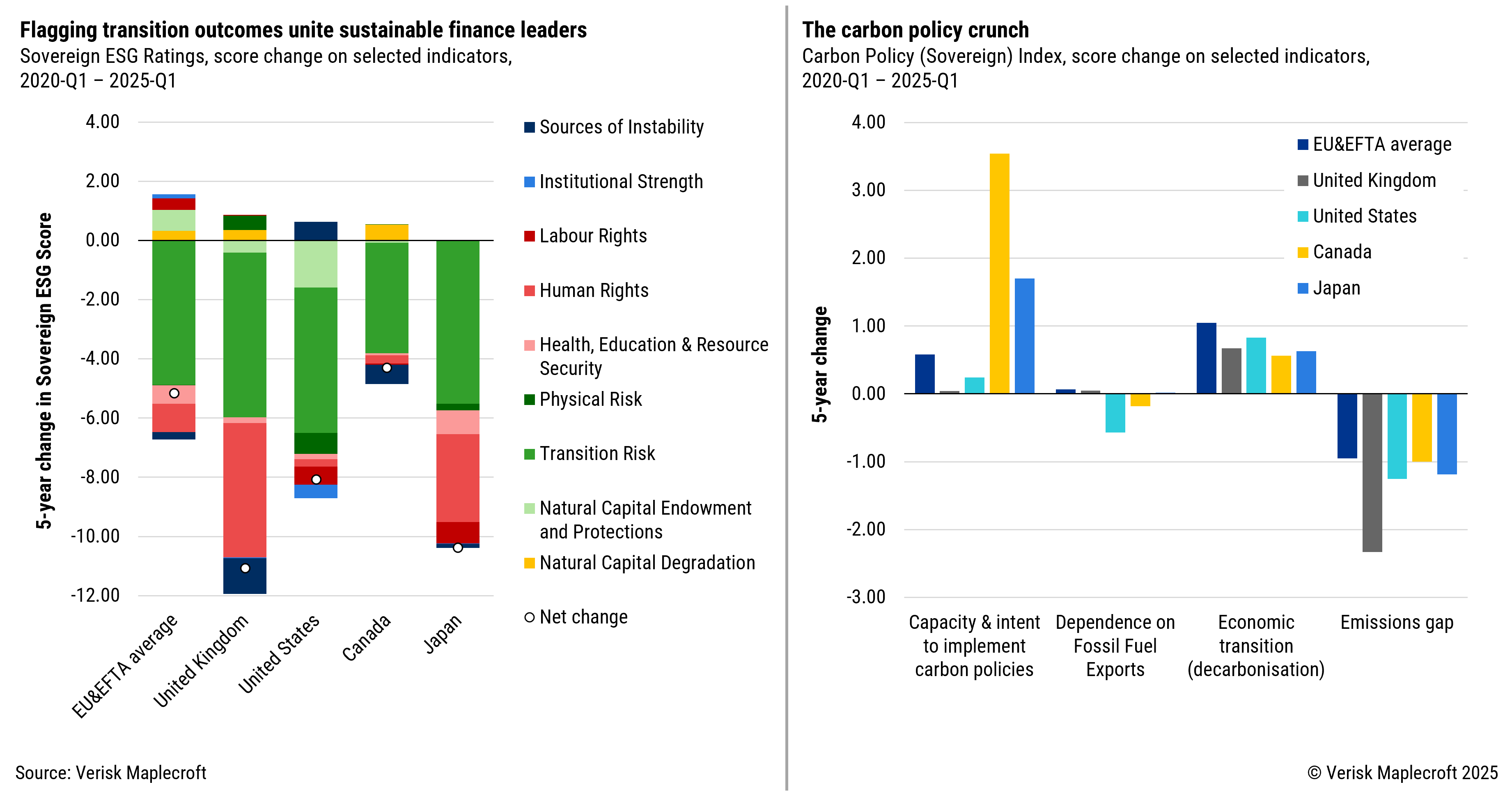

The central theme is climate politics. As Figure 1 shows, the last half-decade has seen the key sustainable finance hubs become less sustainable overall, but especially on transition risk. Europe and North America are increasingly falling behind their emissions targets despite modest reductions in GHG intensity, and momentum on carbon policies since 2020 has been uneven. The costs of transition have begun to bite, exacerbated by broader cost-of-living pressures, making the road to a low-carbon economy look decidedly rocky.

Sustainable finance, however, is still kicking and breathing. The review of European rules may result in a much-needed streamlining if Brussels is able to resist business and some member state calls for a significant rollback. Despite shifts in voter preferences, most asset owners see climate and nature risks as increasingly material and will reward managers who account for them. The mounting toll of extreme weather speaks for itself in this respect. Banks will ultimately answer to their clients and prudential obligations, even if they must be cannier about politics. Generational wealth transfers will increase appetite for credible transition finance or impact products, even as regulators and sceptics do away with an earlier generation of marketing-driven initiatives.

2. World already off track, as tighter emissions targets loom

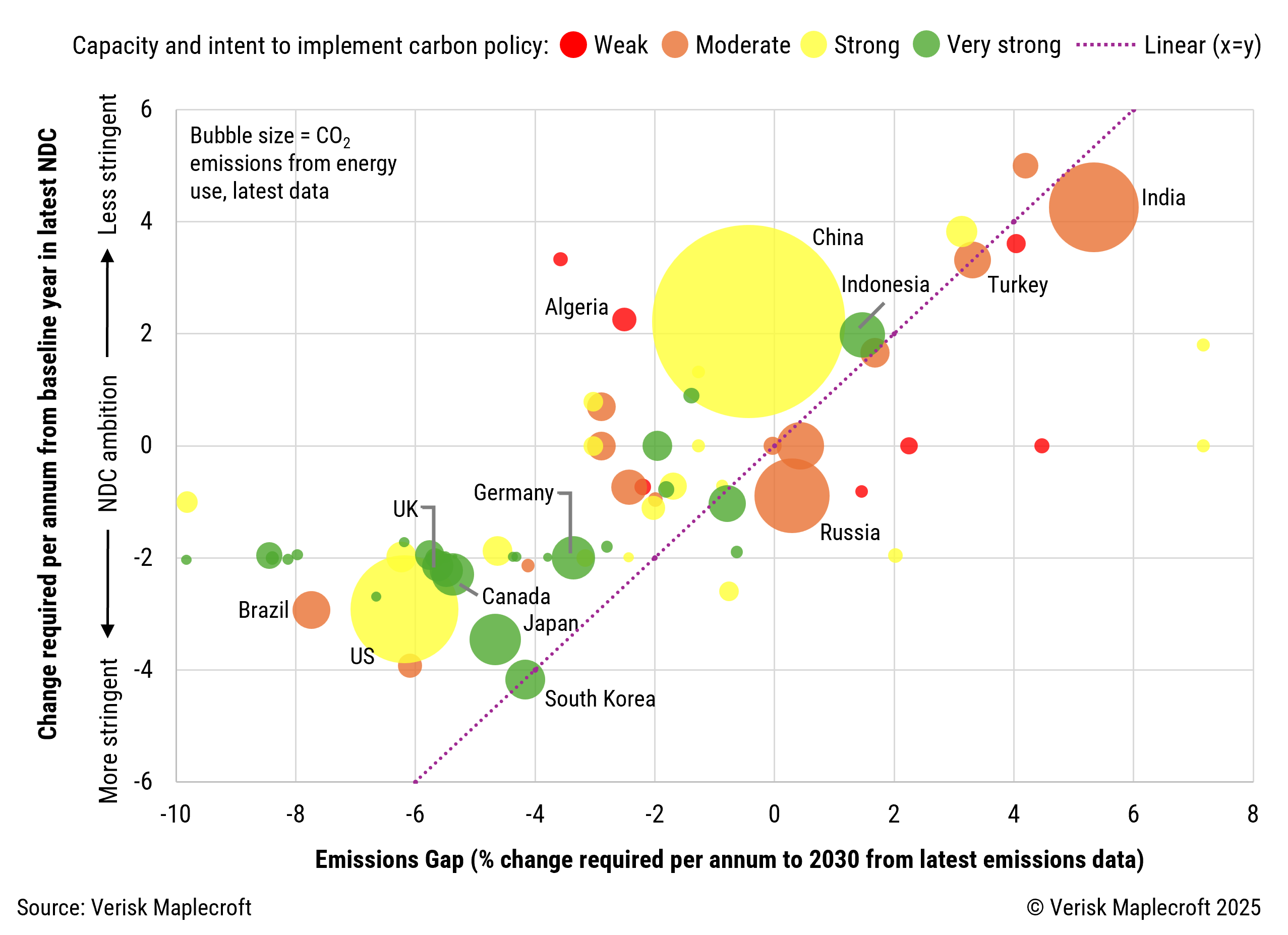

One of the most significant developments on the sustainability horizon this year is the submission of the third generation of Nationally Determined Contributions: NDC 3.0. Countries are supposed to commit to faster emissions reduction, but in many important cases are not on track to meet existing targets. Figure 2 shows the magnitude of required annual adjustments out to 2030, both from the baseline year of their existing NDC targets (y-axis), and according to the Emissions Gap pillar of our Carbon Policy-Sovereign Index (x-axis), which helps organisations evaluate the remaining distance to goals from latest data.

Countries sitting on or near the x=y line are tracking against targets – with South Korea leading the way – but those above it, including many high-emitting developed states (see bottom left-quadrant), will need to increase the pace of emissions cuts just to meet their current 2030 targets. They broadly have the carbon policy environment to enact more aggressive cuts – denoted by the yellow and green groupings on the chart – although in the current political climate nothing can be taken for granted.

Countries in the top right quadrant are still in the expansionary phase, most importantly India whose emissions are not expected to peak until the mid-30s at the earliest for a net zero 2070 target, while China, whose NDC allowed for an average 2.2% annual increase in emissions, has now seen emissions exceeding the target, tipping its emissions gap negative.

With the sum of existing global commitments, let alone action, still well behind the demands of the Paris Agreement, and the departure of the US from the treaty and its commitments, the burden of expectation on the forthcoming NDCs 3.0 is immense.

3. The sustainability of AI

The technology sector closed 2024 as one of the top-performing industries, largely driven by the surge of interest in generative AI. As the sector transitions from initial excitement to broader business adoption, 2025 will bring a deeper focus on the long-term sustainability of this technology. While the growing carbon footprint of the sector will be a key consideration, broader social and political challenges – such as the impact of automation on employment, human capital, and consumer wellbeing – will also come into sharper focus.

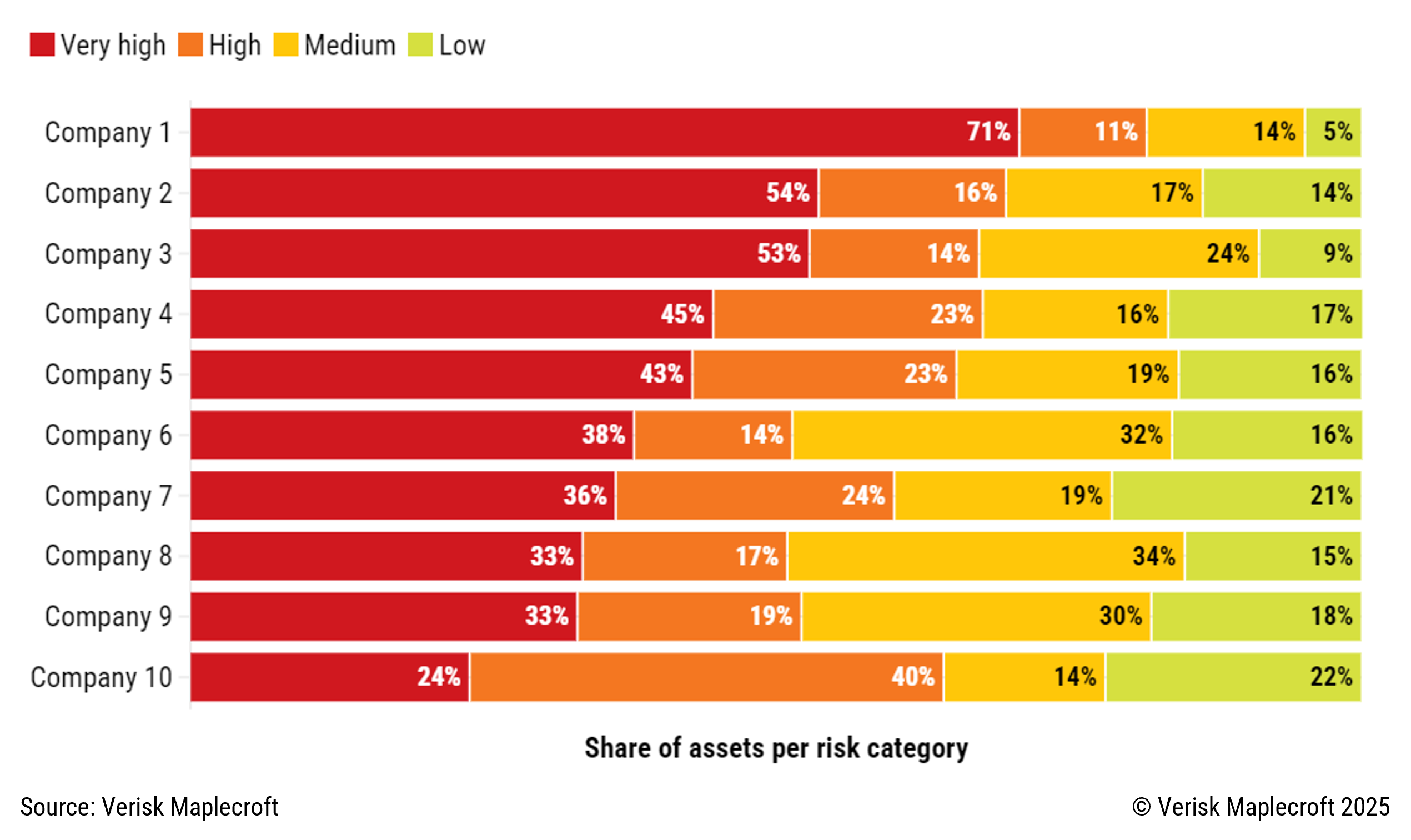

As with any sectoral analysis, investors will need to account for company-specific factors – whether it’s climate, social, political or environmental risks. Our Asset Risk Exposure Analytics (AREA) reveal that, on average, 43% of assets across the 10 largest technology companies are at extreme risk of water stress. However, there is significant variation: the most exposed company has nearly 71% of its assets in regions facing extreme water stress, while the least-exposed company has only 23% of assets in similar high-risk locations. Among US tech hotspots alone, water-stressed locations at the bottom 10% of our very high-risk range include Colorado – particularly in the Denver area, California with hotspots around San Diego, and Arizona's Scottsdale and Phoenix. Investors will want to account for these variations to avoid generalised approaches and be best positioned to identify leaders and laggards.

4. Human rights: the canary in the coal mine?

Human rights are also rising up the regulatory agenda. With the proposed ‘omnibus’ review of the EU’s sustainability legislation and the recently launched Taskforce on Inequality and Social-related Financial Disclosures (TISFD), there has never been a better time to have a comprehensive view of the social impacts of an investment portfolio.

Worsening human rights in a country can be the canary in the coal mine for sovereign investors – an early warning of political and economic shifts that could dampen investment appetite. Turkey and South Africa were prime examples over the past decade, where weakening human rights presaged political crises, widespread unrest and bond sell offs.

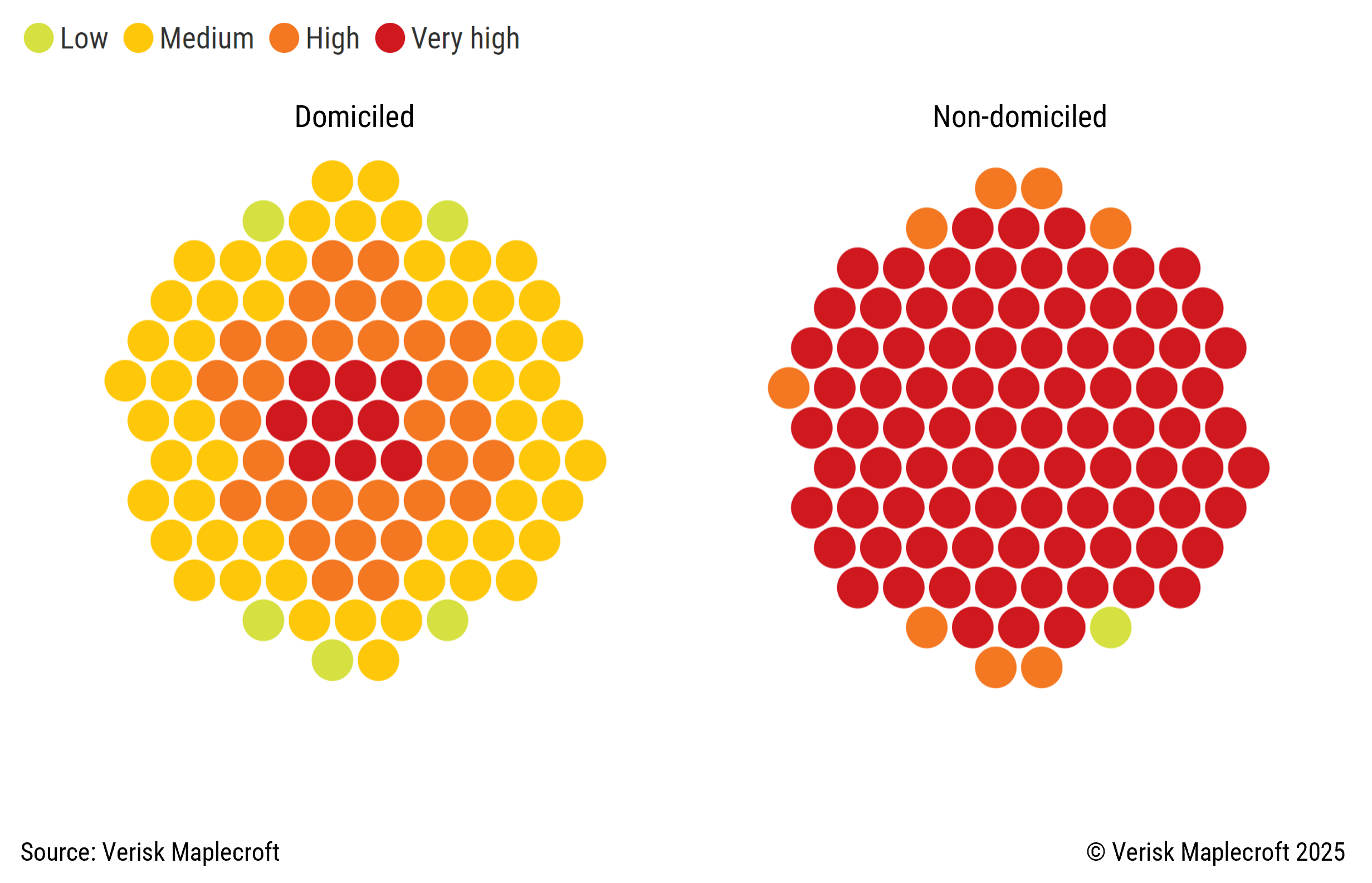

But it is not just sovereigns that investors need to pay attention to. Data from our Asset Risk Exposure Analytics (AREA) finds that across the world’s 100 largest companies by market cap, human rights are a significant issue for them outside the country they are listed in. These organisations have 44% of assets located abroad, where their exposure to human rights rises exponentially. Taking the example of Modern Slavery, only 9% of these companies’ assets are exposed to very high risk levels in their host countries, but that jumps to 91% for non-domiciled assets.

In a world of greater uncertainty, in which we are witnessing a fundamental shift of global trade and supply chains, it is increasingly important for investors to gain far greater visibility over their exposure to social risks. This entails building a more holistic view of human rights risk, by country and industry, across the entire asset footprint of the companies they invest in – and regulators are going to expect this.

5. From taskforces to interconnected risks

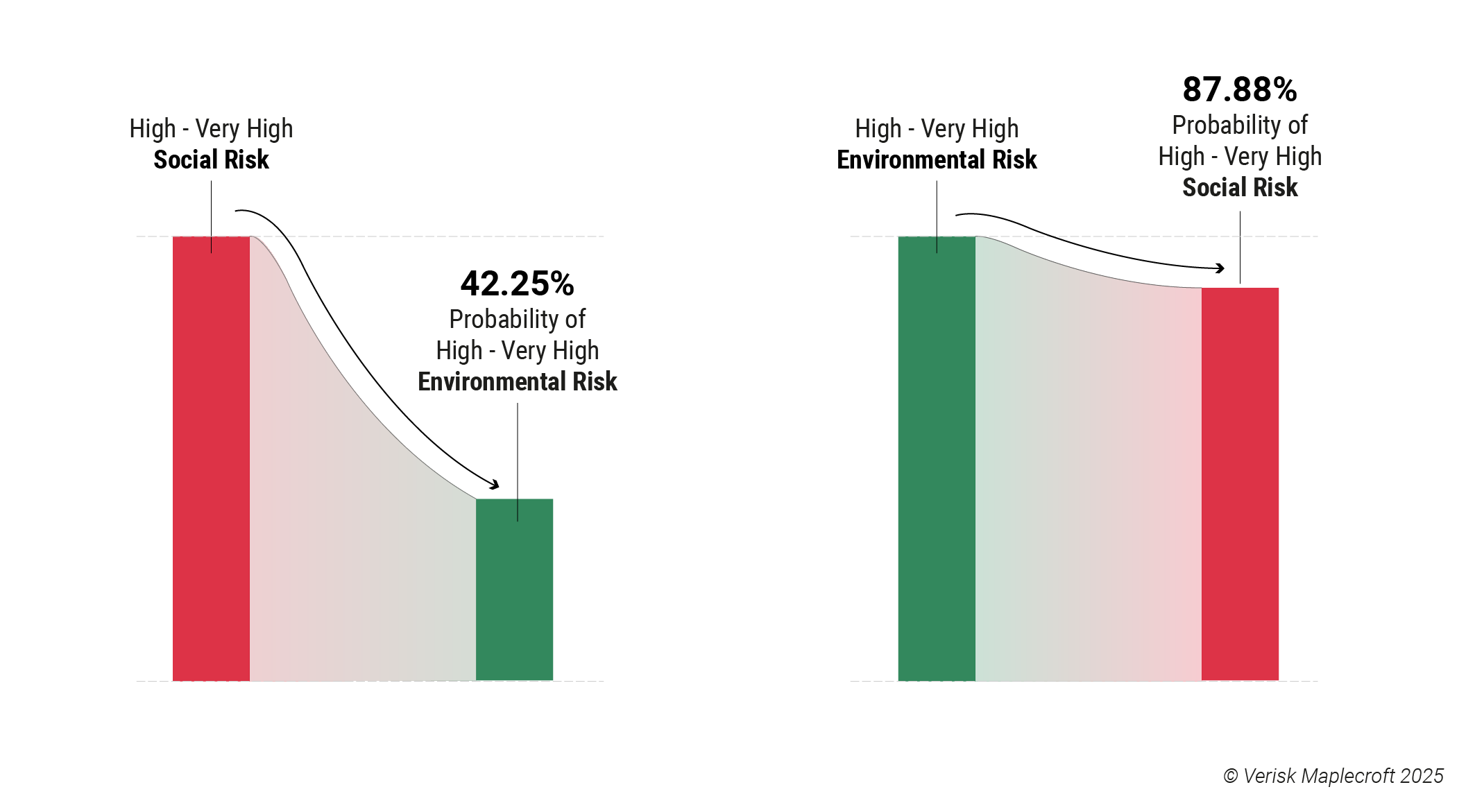

ESG risk analysis is set to evolve from a siloed, single-issue approach to a more interconnected framework. This shift reflects a growing recognition that ESG risks are interrelated and require a holistic assessment. Illustrating this, our Asset Risk Exposure Analytics (AREA) data shows that across Germany’s DAX companies, assets that are exposed to high or very high social risks are 42% likely to also be at high to very high environmental risks; conversely, assets at high or very high environmental risk face an 88% likelihood that social risks will be similarly elevated (see Figure 5).

With foundational taskforces addressing climate (TCFD), nature (TNFD), and social risks (TISFD) now in place, the focus will be on fulfilling existing requirements rather than introducing new ones. The ongoing review of EU sustainability legislation signals that the regulatory discourse is maturing, with non-financial risks increasingly expected to be assessed with the same rigor as financial risks. While the scrutiny of ESG may increase under the new administration in Washington, intensifying natural hazard impacts, the degradation of biodiversity and a worsening human rights environment will remain key issues for investors.

Ultimately, 2025 will see ESG return to its core purpose: identifying and managing non-financial risks across environmental, climate, social, and (geo)political factors. Rather than a mere compliance exercise, ESG will be about embedding these factors into risk management to better navigate a complex, interconnected risk landscape.