Sustainable finance - 5 trends to watch

The Trendline

by Emma Whiteacre and James Lockhart Smith,

Proliferating regulations and the urgency of environmental and social challenges will continue to force sustainable finance to mature. Labelled debt issuance, in all its varieties, will head towards USD1 trillion this year. But while the energy transition accounts for a growing share of issuance, capital and a clear path forwards are lacking for many of the carbon-intensive industries and countries that need them most. Asset managers looking to support the Just Transition will also need to monitor weak human and labour rights metrics across a range of countries.

Fossil fuel pledge putting pressure on oil producers

COP28’s watershed pledge to transition away from fossil fuels will see markets begin to diverge on climate. 2024 will be a year of opportunity for transition funds focused on renewables, clean tech and infrastructure, but carbon-intensive companies and countries will come under increasing pressure from investors. This dynamic is set to catalyse a new focus for carbon-intensive sovereign issuers on climate transition mechanisms this year, including transition bonds and blended finance.

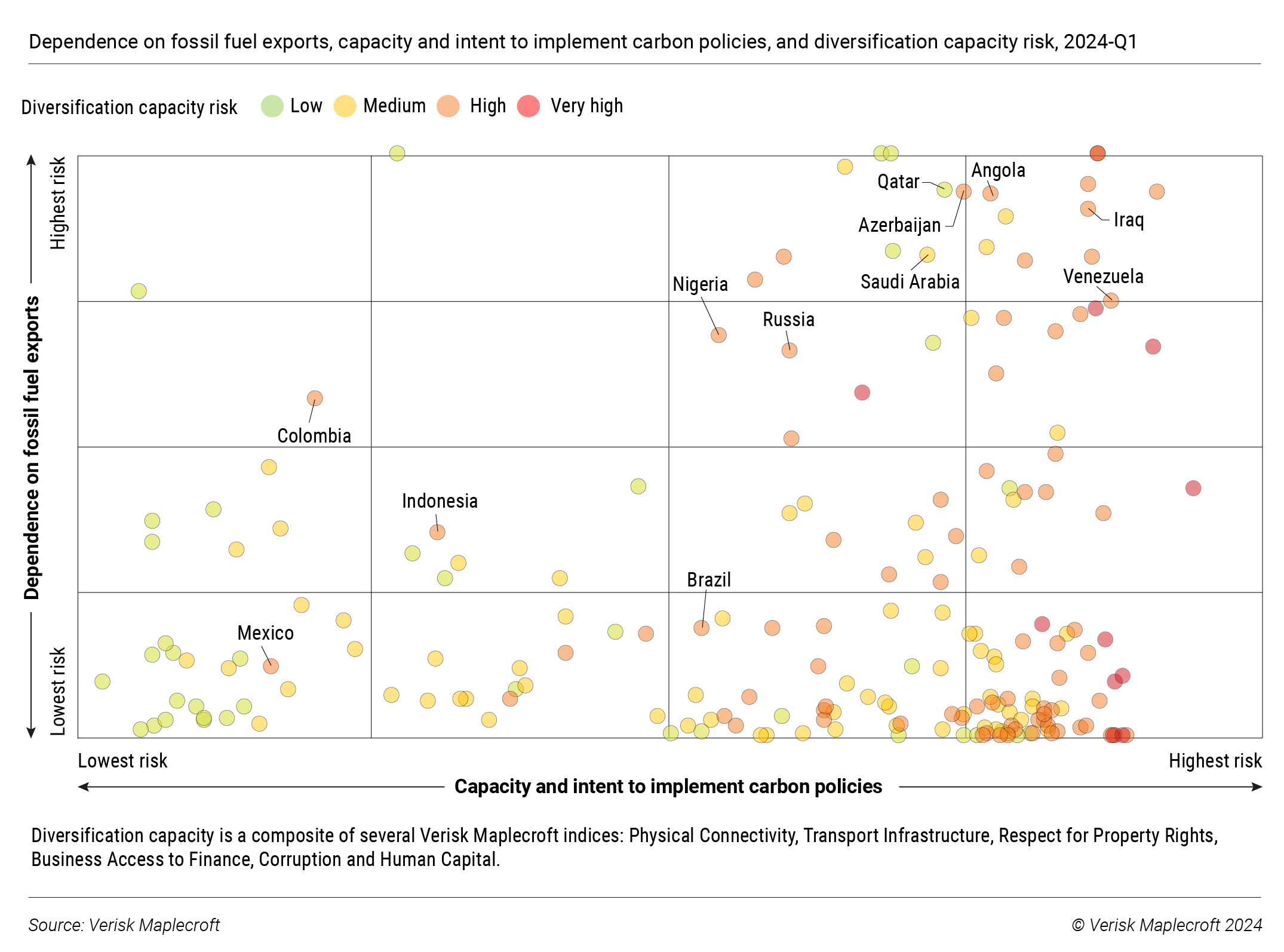

Only 1% of high-emitting companies have aligned capex plans with decarbonisation, and our data shows countries aren’t doing much better. Forty-seven countries are at very high risk in our Carbon Policy Index, reflecting inadequate action, with 111 at high risk. At the same time, 31 countries are high or very high risk for Dependence on Fossil Fuel Exports.

Fossil fuel consumers and better-resourced producers will remain largely impervious for now; but weaker producers, and their state-owned companies, will feel the pinch even with oil prices at current levels. They need support for transition, but transition could make them temporarily riskier, while lenders are also wrestling with stakeholders’ expectations on portfolio decarbonisation.

Labour rights risk being compromised amid focus on decarbonisation

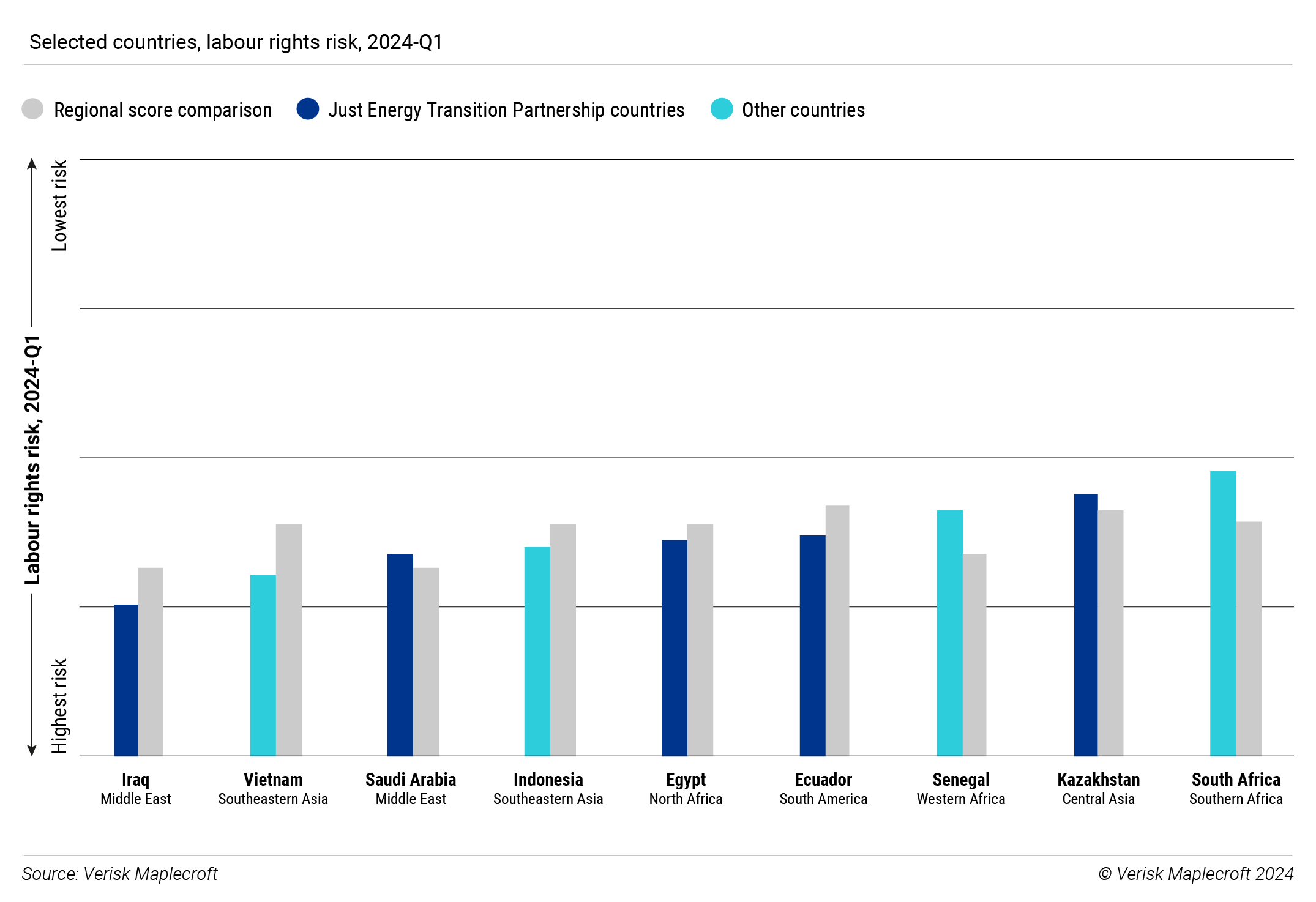

We expect a renewed focus this year on inclusion and fairness, in line with the Paris Agreement commitment in 2015 to a Just Transition. For investors, this means assessing the secondary impacts and co-benefits of green frameworks and transition plans and monitoring the social performance of investee companies and governments. Transition may be an enormous task, but neglecting social risks is a recipe for problems further down the road.

If one thing is clear, it’s that work needs to be done. The Just Energy Transition Partnership model - first agreed with South Africa at COP26 in 2021, which seeks to address workers’ needs while delivering industrial policy changes, has since been adopted by Indonesia, Vietnam and Senegal. But our data shows these countries are high risk for labour rights, encompassing child and forced labour and occupational health and safety. Elsewhere, countries facing the most significant transition risk are also some of the weakest on social considerations. Energy-producing emerging markets that register as high risk across our human and labour rights indices include Egypt, Ecuador, Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

COP29: Climate finance should focus on countries most exposed to both physical and transition risks

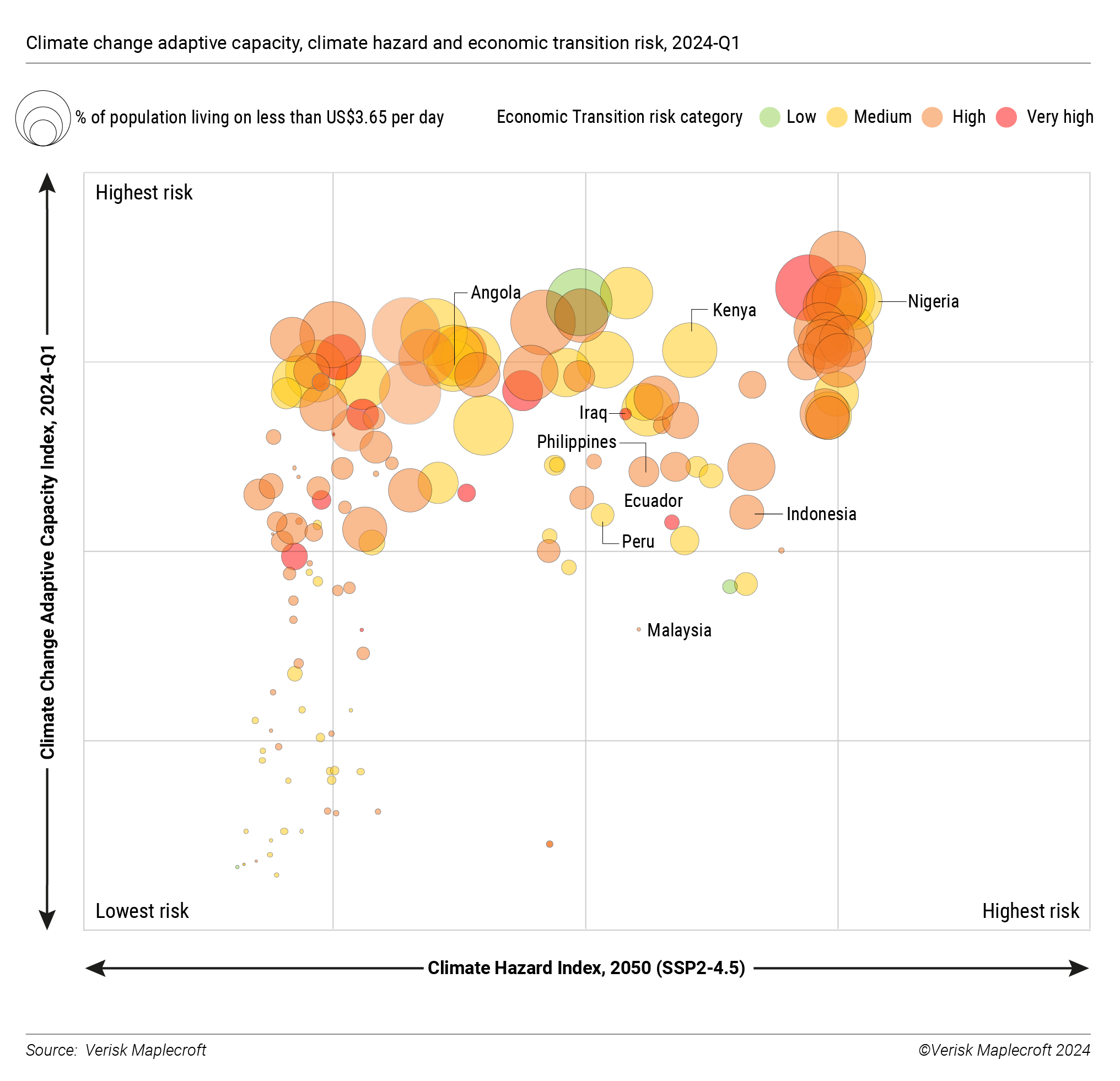

COP29 may not command as much of the global spotlight in 2024 as the COP process has done in recent years, but it will be a crucial event to watch for investors. Climate finance will be top of the agenda, as countries are due to finalise a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) to build upon the USD100 billion agreed in 2009 (but only met in 2023).

An ambitious step-up is required. According to our data, countries most in need of external support are facing a confluence of challenges – significant exposure to physical risks by 2050, lack of finance and adaptive capacity to combat these risks, and the inability to implement an effective economic transition away from carbon. This is true across much of sub-Saharan Africa, but also in some Latin American, Southeast Asian and weaker Middle Eastern nations.

High levels of poverty and weak growth profiles will undermine domestic resilience, making external financial support critical. Beyond finance, we should see continuing negotiations around fossil fuel phase-out and a questionable reliance upon transition gas and carbon capture and storage.

Investors stepping up direct policy engagement on emissions and adaptation

While engagement with investees to encourage better governance and sustainability outcomes is well established for equities and corporate fixed income, it’s more nascent in sovereign debt. This could change in 2024, at least around climate policy. The Principles for Responsible Investment has recently coordinated a pilot collaborative sovereign engagement initiative in Australia, representing USD8 trillion of AUM, and is exploring extending the programme to other sovereigns.

Sovereign engagement is different to – and harder than – its corporate equivalent for a range of well-known structural reasons: for example, investors don’t own countries, and political leaders answer to different stakeholders. However, we expect investors to begin to work past these challenges to deliver modest outcomes on areas of emissions policy. Beyond Australia, top of their target list should be major emerging markets such as Brazil and India that both materially contribute to global emissions and are severely exposed to climate risks.

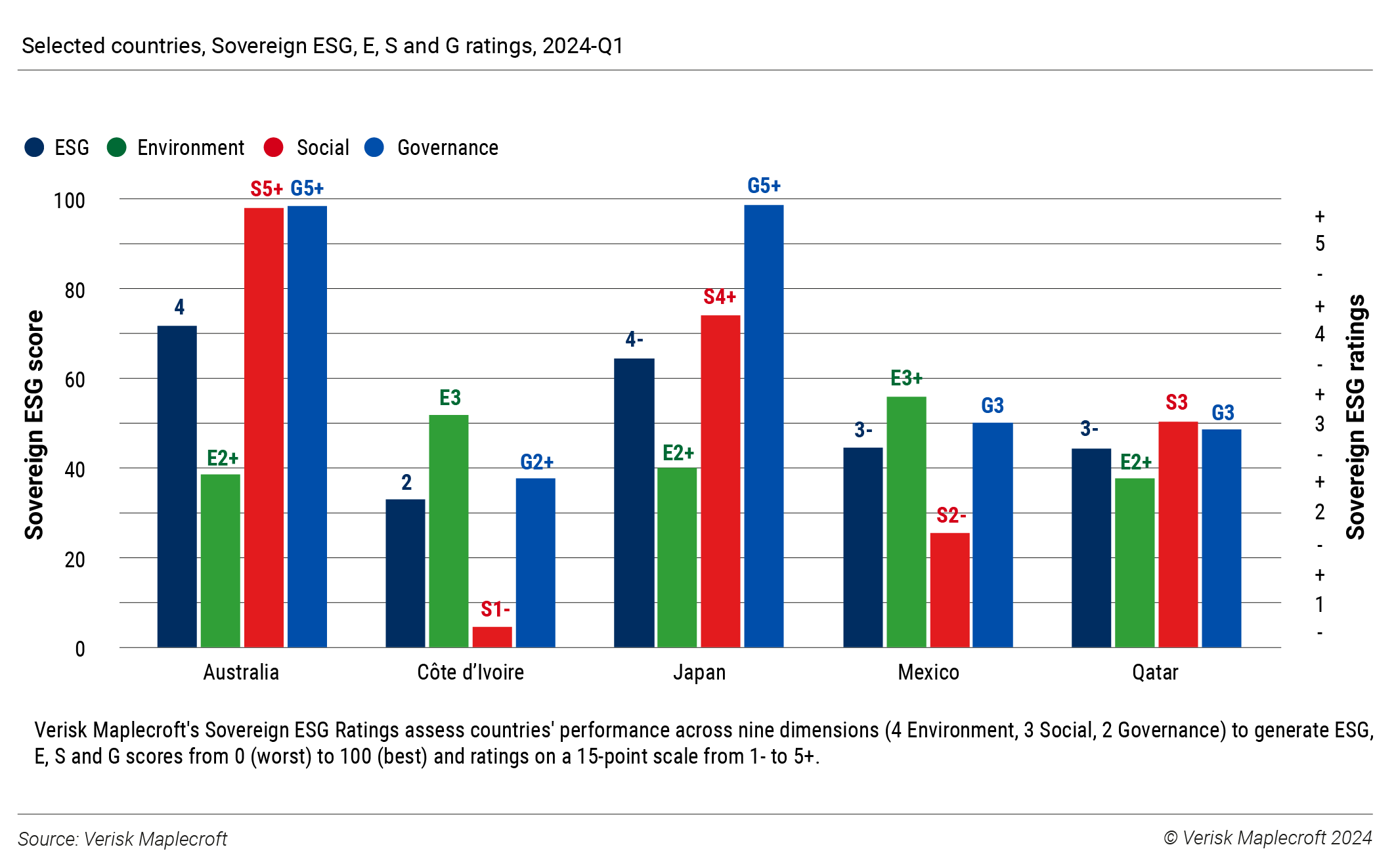

Improving market conditions point to strong year for GSS+ issuance

Global green, social, sustainability (GSS) and other labelled bond issuance could peak this year as corporates and governments look to capitalise on easing global interest rates and investor demand. After a sharp decline in sovereign GSS+ issuance last year, we expect a rebound in 2024, with Australia (sovereign ESG rating 4, where 5+ is the best possible score), Qatar (3-), and Kenya (2+) among those poised to issue, following well-received sales from Mexico (3-), Cote d’Ivoire (2) and Japan (4-).

With biodiversity and social risks rising up the agenda, we expect investors to show increasing appetite for innovative structures. This includes debt-for-nature swaps, blue bonds for marine conservation, orange bonds for gender-focused initiatives, and blended approaches for developing markets that would otherwise struggle to access funding. New EU green bond standards, due to come into effect until January 2025, show the market is maturing, and investors can expect greater transparency and stronger validation.