Rwanda and Republic of Congo top list of African sovereigns improving their ESG performance

by Winifred Michael,

The uncertainty caused by the war in Ukraine and the Covid-19 pandemic has encouraged many sovereign debt investors to pivot towards safe-haven assets in the form of developed market bonds.

But it is important to note that several emerging market issuers, including those in sub-Saharan Africa, have made efforts to improve aspects of their environmental, social and governance systems – even amid global health and cost of living crises.

For investors looking to support progress and accelerate positive change in countries with weaker ESG profiles but improving trajectories, paying attention to ESG trends and signals can provide valuable insight into countries they might previously have overlooked.

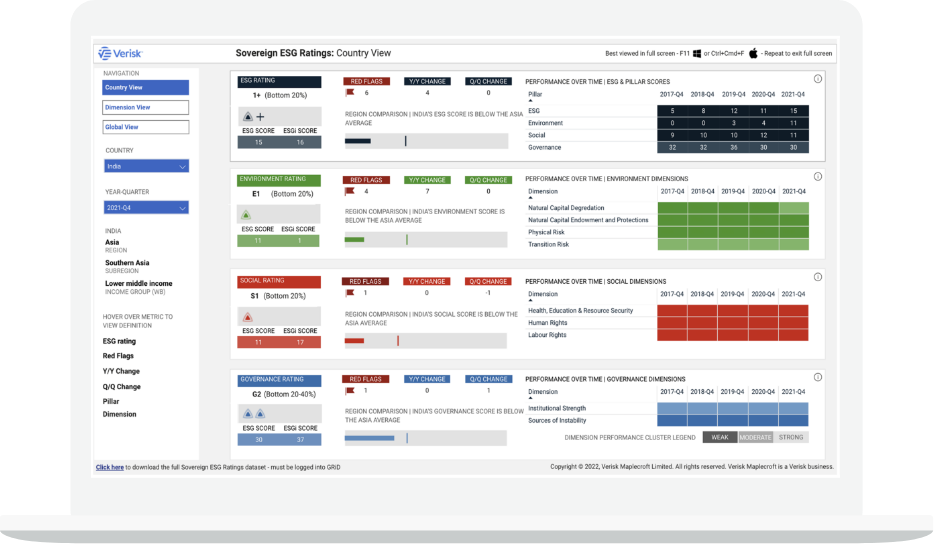

Tapping into the data from our Sovereign ESG Ratings, which track the trajectory of risk for all countries on a quarterly basis, we identify two African countries making progress. And, conversely, two that might be falling behind the curve.

E and G gains drive positive trajectory in Rwanda and Republic of the Congo

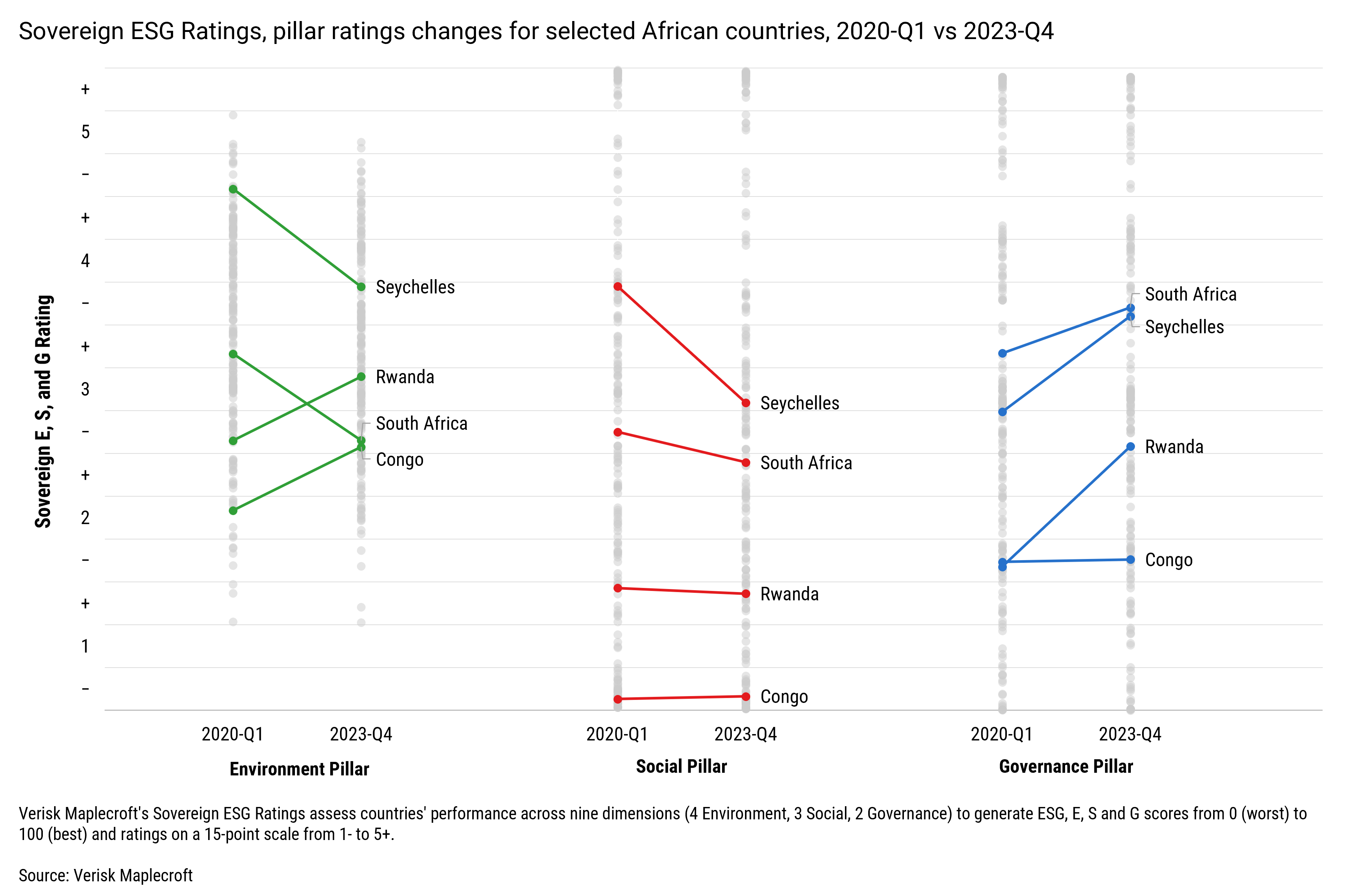

Rwanda and Republic of the Congo are the two sub-Saharan African countries that have seen the biggest improvement on our Sovereign ESG Ratings since 2020-Q1.

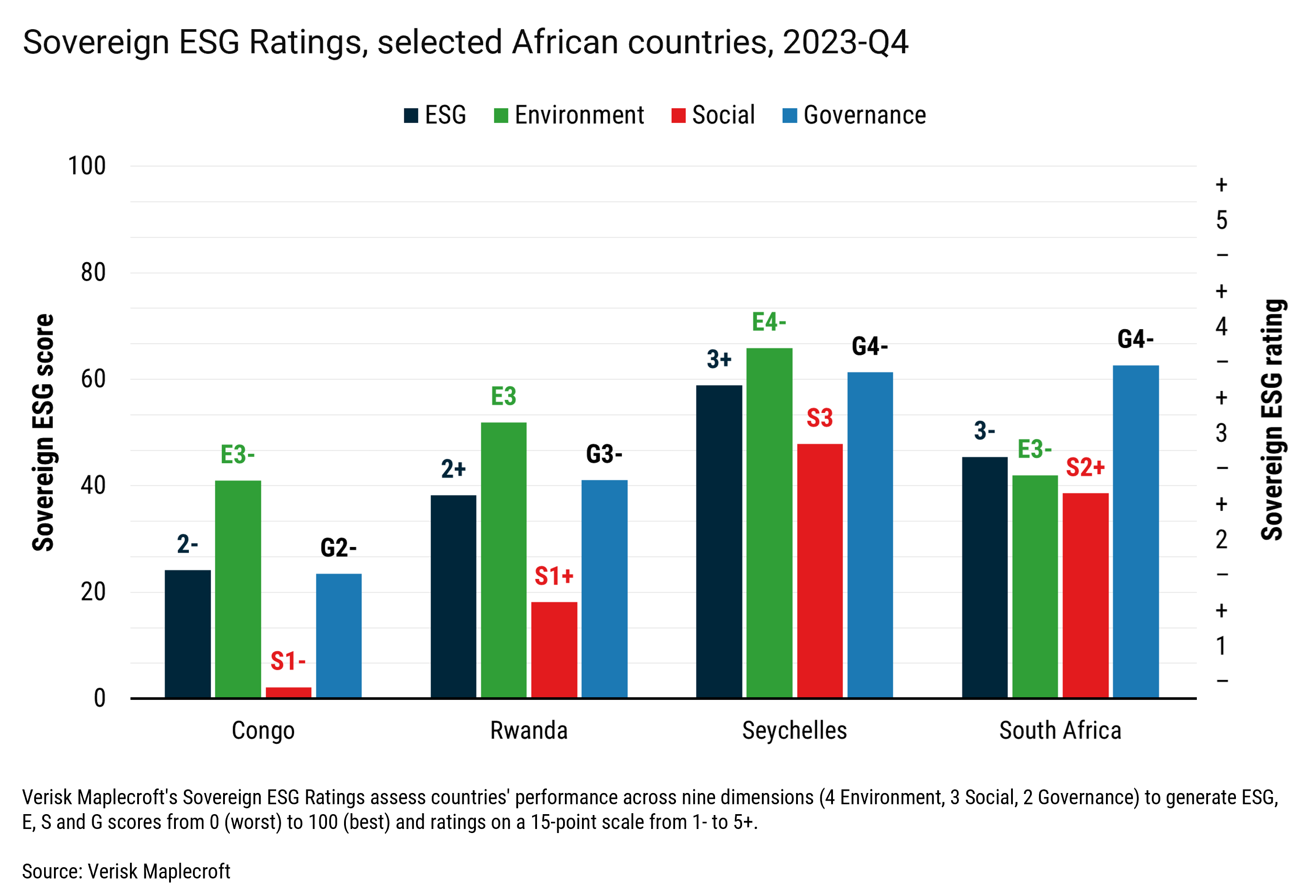

Digging into the scores shows that Rwanda has moved from a rating of 2 to 2+ in the past three years, largely as a result of improvements on the Transition Risk and Sources of Instability dimensions of our Environment (E) and Governance (G) pillars. Meanwhile, Republic of the Congo has moved from 1+ to 2- as a result of gains on the E pillar, driven by notable improvements on the Natural Capital Endowment and Protections dimension.

Rwanda’s positive trajectory on the E pillar reflects the efforts it has made to narrow its emissions gap. In September 2021, Kigali launched a scheme to plant 43 million trees in the country, and the government has since revised its green growth strategy to implement climate change action into all economic sectors, helping to position Rwanda as a candidate for international funding and private sector investment for low carbon development. These revisions are part of an effort to achieve Kigali’s target of reducing emissions by 38% by 2030 and to be carbon-neutral by 2050, indicating the government’s increased intent to implement carbon policies.

Rwanda’s commitment to climate policy has also been aided by a reduction in risks on the G pillar, including on sources of instability like crime and terrorism, which has provided more room to focus on other policy areas such as climate change. Reduced criminality and terrorism will also reassure investors over risks to the tourism sector, an important contributor to government revenue, and will minimise the need for heavy spending on security.

Meanwhile, Republic of the Congo’s improvements on the E pillar have been driven by an increase in protections for biodiverse areas. The government hosted representatives of the Congo, Amazon and Borneo rainforests at the Three Basins Summit in October – reflecting Brazzaville’s efforts to raise external finance for the protection of its vast tropical forest.

Increasing E and S risks weigh on performance in South Africa and Seychelles

The weakest African performers on the Ratings since 2020-Q1 have been Seychelles (rated 3+, down from 4) and South Africa (rated 3-, down from 3), driven by declines on dimensions underpinning the Ratings’ E and Social (S) pillars, including Transition Risk, Labour Rights, Natural Capital Degradation and Health, Education and Resource Security. This reinforces that, as investors are increasingly understanding, there is a profound interdependence between environmental and social issues.

Indeed, in Seychelles, fossil fuels have increased as a share of exports, but notably energy efficiency in the economy has decreased. The latter could be a contributing factor to increased food security risks in the country, as seen in the uptick in food price inflation. As the use of energy for food production increases, farmers pass their raised expenses on to consumers.

South Africa, meanwhile, remains one of the world’s largest carbon emitters as a result of its high dependence on coal-fired power stations. The country’s carbon emissions gap has widened since 2020-Q1, with air quality risks increasing in tandem.

Furthermore, given that the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) now requires asset managers to report on human rights abuses in their sovereign portfolios, we highlight that Seychelles has seen a deterioration in its performance on the Labour Rights dimension of our S pillar. This includes an increase in the extent of children employed in hazardous work in the country, reflecting reduced adequacy in the penalties for child labour violations.

South Africa’s performance on the Labour Rights dimension has improved slightly, owing to reduced occupational health and safety risks, but such improvement has been limited by its poorer performance on child labour. The adequacy of the resources needed for the labour inspectorate to enforce laws on child labour has deteriorated in the country, reflecting weaker commitment to prohibit the worst forms of the practice.

While investors may be concerned about Seychelles and South Africa’s worsening performance on our Sovereign ESG Ratings, improvements on the Institutional Strength dimension of our G pillar - thanks to more judicial independence in the case of South Africa, alongside improved democratic governance and reduced corruption and crime risks in Seychelles - highlight opportunities for the two sovereigns to better utilise their relatively strong institutions to tackle environmental and social challenges.

Investors have an opportunity to drive African ESG progress

While Africa’s relatively weak ESG performance has often served to constrain investment appetite, improvements among lower-rated sovereigns such as Rwanda and Republic of Congo should help to bolster investor confidence in the region. The increased willingness to deal with ESG challenges also provides sovereign debt investors with a clear opportunity to engage with these issuers to accelerate progress.

At the same time, the relatively strong governance systems of sovereign issuers like Seychelles and South Africa could allow sovereign debt investors to effectively support their progress on sustainability goals, even as their performance on E and S issues weakens.

As countries travel along the road towards a just energy transition and the task of fulfilling the Sustainable Development Goals becomes more urgent – especially for sub-Saharan African countries – as the 2030 deadline nears, the deep interconnection between environment, social and governance issues will become ever more apparent. Investors will increasingly need to take a more holistic approach to navigating these complex systems.