With politics rocking bond markets, sovereign ESG investors might be tempted to conclude that their job would be easier without so many elections in the mix. At the same time, democratic governance is likely key to their ESG policy commitments. So at the midpoint of a poll-heavy 2024, we’ve delved into the data to help frame your approach on this critical issue, including in relation to some of the key electoral dramas giving most cause for concern this year.

Elections do bring uncertainty

Before we even get to what the data shows, it’s worth acknowledging the obvious. Yes, deeply embedded rights and institutions usually survive changes in government, and so does fiscal and economic competence. Yes, democratic change every few years reduces the risk of blow-ups further down the line. But genuine electoral processes always have the potential to push countries in radically different directions in all areas of policy, including on sustainability.

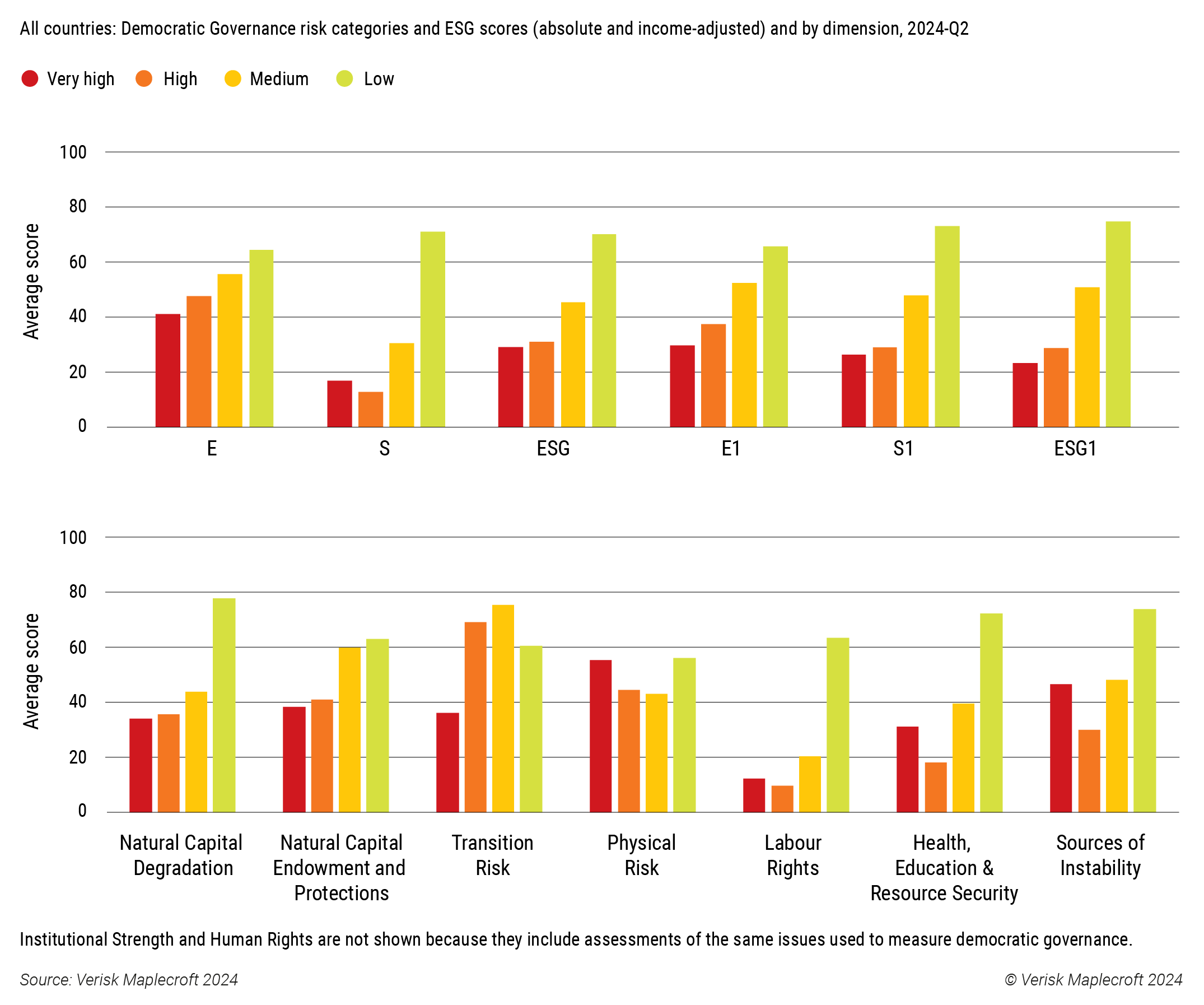

Robust democratic governance strongly associated with better ESG outcomes

Take a look at Figure 1, which pulls on data from our Sovereign ESG Ratings. Here, we’ve laid out how performing at different levels on our Democratic Governance Index is associated with countries’ ESG, E and S scores – both absolute and with adjustments to strip out income bias – as well as with other specific dimensions of ESG. This very clearly shows that stronger democracies (countries in the medium and low risk categories) deliver better ESG outcomes than both authoritarian states and weak democracies (those in the very high and high risk categories).

Investors with a focus on ESG may bemoan election-related turmoil as much as anyone this year. But this evidence strongly reaffirms the long-term case for putting countries’ democratic credentials at the centre of any screening or tilting; and the value of engagement to bolster democratic commitments. Portfolio managers looking to construct sovereign bond funds aligned with SFDR Article 9 (or indeed Article 8) can pay particular attention to democracy as a way – at least at a portfolio level and over the medium to long term – to maximise the likelihood of good overall ESG outcomes, and at the same time reduce the extent of Principle Adverse Impacts.

The autocratic advantage is real, but limited

There’s an exception to the above pattern lurking in Figure 1. Authoritarian countries in the very high risk category - such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Vietnam – outperform their weakly democratic counterparts on Social risk overall, and on the specific dimensions of Labour Rights and Health, Education and Resource Security. They also do much better – unsurprisingly – on Sources of Instability, which measures crime, civil unrest, government stability and the threat from terrorism. Considerably more policy stability and certainty, extensive distribution structures to deliver public services and the scope for continuing improvements in human capital are the kind of fundamental characteristics that investors seek out.

However, both regime types do much worse on ESG than established democracies; and as shown in the income-adjusted scores above, autocracies fall behind once wealth levels are taken into consideration. To the extent they do better than weak democracies on any areas of ESG, it’s probably because they are wealthier, not because they are less free. For asset managers who value the investment stability that authoritarian regimes can offer, the implication that environmental and social outcomes are compromised alongside governance may give pause for thought, given the potential longer-term implications for creditworthiness that may result.

Elections are a critical opportunity for ESG course correction

Several countries with elections this year, including some that have suffered recent setbacks in democratic governance, are also now coming under pressure on ESG delivery. A broad array of ESG issues – like climate and energy, water stress, pollution, rights, crime, and corruption – are influencing election agendas and affecting the fortunes of incumbents. While the resulting negative publicity can dampen market sentiment, the electoral process opens the way for policy change.

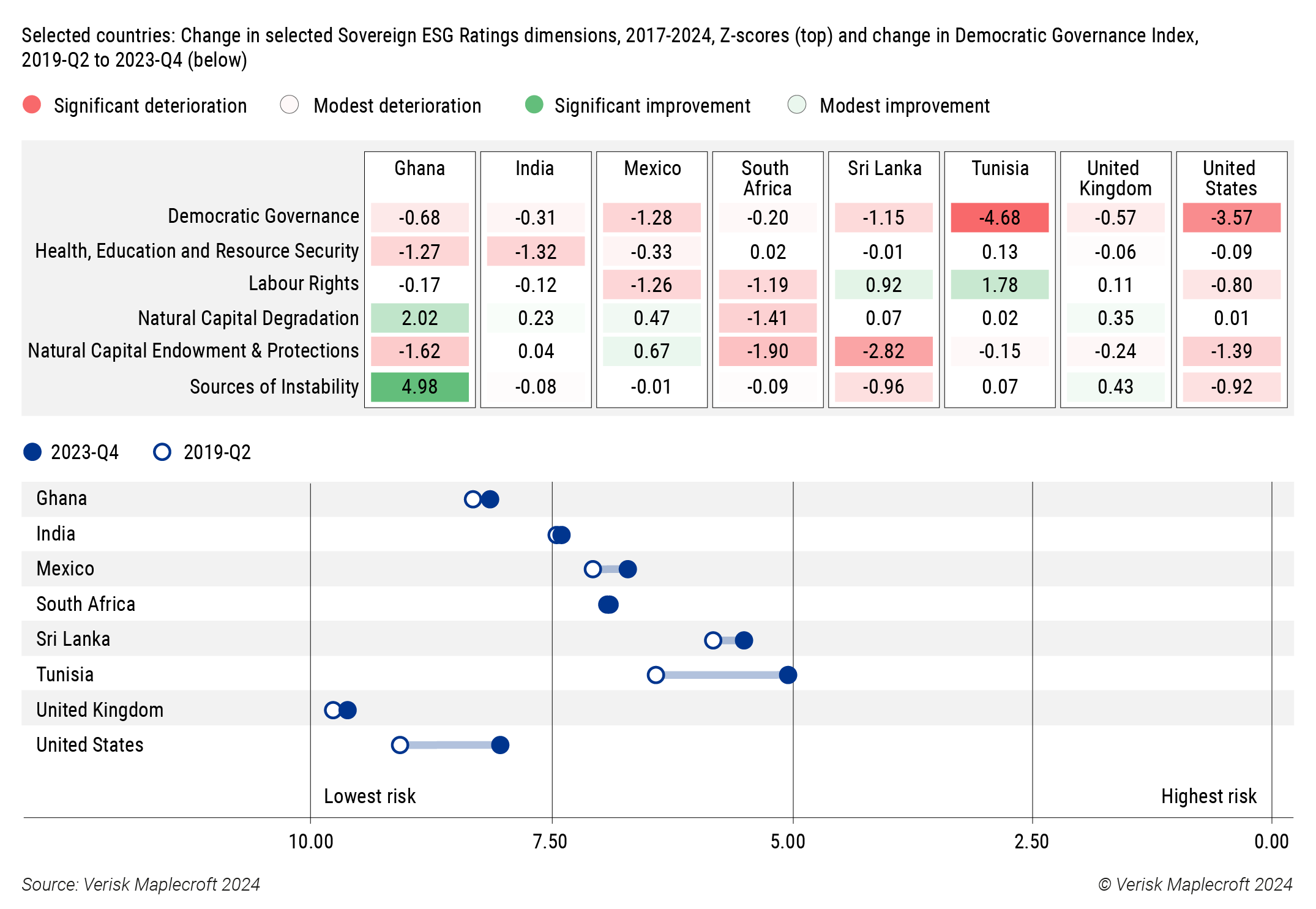

For example, as shown in Figure 2, South Africa and India, both medium risk, have seen a modest weakening of their democratic governance profile over the past five years, and considerable weakness across ESG issues. The ANC and BJP parties respectively have both been punished at the polls with a significantly weakened mandate, at least in part for failures to address significant environmental and social challenges over their decade(s) in power. But while the political risks of their current circumstances are considerable, the relatively smooth conduct of these elections will reinforce their democratic credentials. The UK also arguably fits this characterisation, with voter discontent with the Conservative party’s handling of a range of social policy issues playing a key role in ushering in political change.

Declining democratic governance should be a major red flag for ESG – particularly this year

The overall lesson from this year’s polls, however, is a gloomier one. Just as it’s good for sustainability when democracies get stronger, the converse is also true. Figure 2 also shows a selection of countries with elections this year where either democracy, or broader ESG, or both, have looked decidedly shaky over the last few years, but where there is no immediate prospect of a turnaround.

In Mexico, for example, President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum has just won a historically unprecedented percentage of votes – but democratic governance has weakened somewhat, mostly due to the undermining of the separation of powers. Amid broader ESG challenges including crime, corruption, eroding personal freedoms and climate impacts, investors are wary about the prospect of a supermajority for Sheinbaum’s Morena party, the lingering influence of her predecessor, and the fiscal straitjacket that will be required to address the state of public finances. While sustainability issues – particularly energy transition investment – are higher on Sheinbaum's agenda, judiciary reforms may undermine legal certainty and stall progress.

Tunisia and Sri Lanka, meanwhile, are both shaping up as countries to watch in the second half of 2024. Sovereign investors are already wary on both given economic turmoil and debt distress. Both are moving from medium risk towards high on our Democratic Governance Index, and are due to host elections before November. Tunisia has seen a sharp slide in democratic governance since 2019 and is now due to hold its first presidential election since President Kais Saied’s 2021 self-coup, with investor sentiment undermined by human rights concerns as well as macroeconomic worries. Sri Lanka’s poll will be seen as a referendum on President Wickremesinghe’s IMF-supported economic reform programme, amid a $12bn sovereign debt restructuring. Corruption, a core component of the Democratic Governance Index, is a significant concern for investors in Sri Lanka and a major impediment to environmental and social progress.

Moreover, this isn’t just about emerging markets. As also shown in Figure 2, the US is also facing significant policy uncertainty amid a weakening democratic profile driven by the erosion of civil and political rights, increased corruption and weaker judicial independence. Its broader ESG profile, already poor for a developed market, has also worsened. As elsewhere, the uncertain political landscape heightens the risk of market volatility, particularly in the event of any further compromise on democratic protections.

Democracy and sustainability go hand in hand, despite awkward moments

If the siren song of well-managed autocracy sounds tempting relative to the rollercoaster risk premia of democracy, it shouldn’t. Per our data, going to the polls turns out to be good for other areas of long-term sustainability, including by giving electorates a vote on key ESG issues. But with a swathe of important economies exhibiting both democratic and ESG weakness around pivotal elections this year, 2024 is shaping up to be an important inflection point for investors – one that may not necessarily end well.