UK’s Seasonal Worker scheme raising human rights concerns in food sector

by Capucine May,

Before Brexit, the UK was almost entirely reliant on overseas workers from the EU for the harvesting of seasonal fruit and vegetables. Since the vote however, the UK Government has ended freedom of movement with the EU and introduced a series of new occupational visa schemes – such as the Seasonal Worker visa programme (SWVP) – designed to control the flow of migrants into the country.

In its current form, the scheme has increased the risk of human rights violations in UK food supply chains. Indeed, the inauguration of the SWVP has contributed to a significant increase in risk for the UK on our Trafficking in Persons Index, seeing the country move from low risk in 2019 to medium risk in 2023-Q3. The UK is now the 19th highest risk country in Europe for human trafficking, up from 29th four years ago.

Figure 1: Trafficking risks in the UK have risen since the inauguration of the SWVP

In this insight, we outline what the UK’s declining score means for operators in the food sector, and the steps businesses can take to navigate the resulting human rights risk landscape.

Non-EU migration leaving food retailers exposed to human rights violations

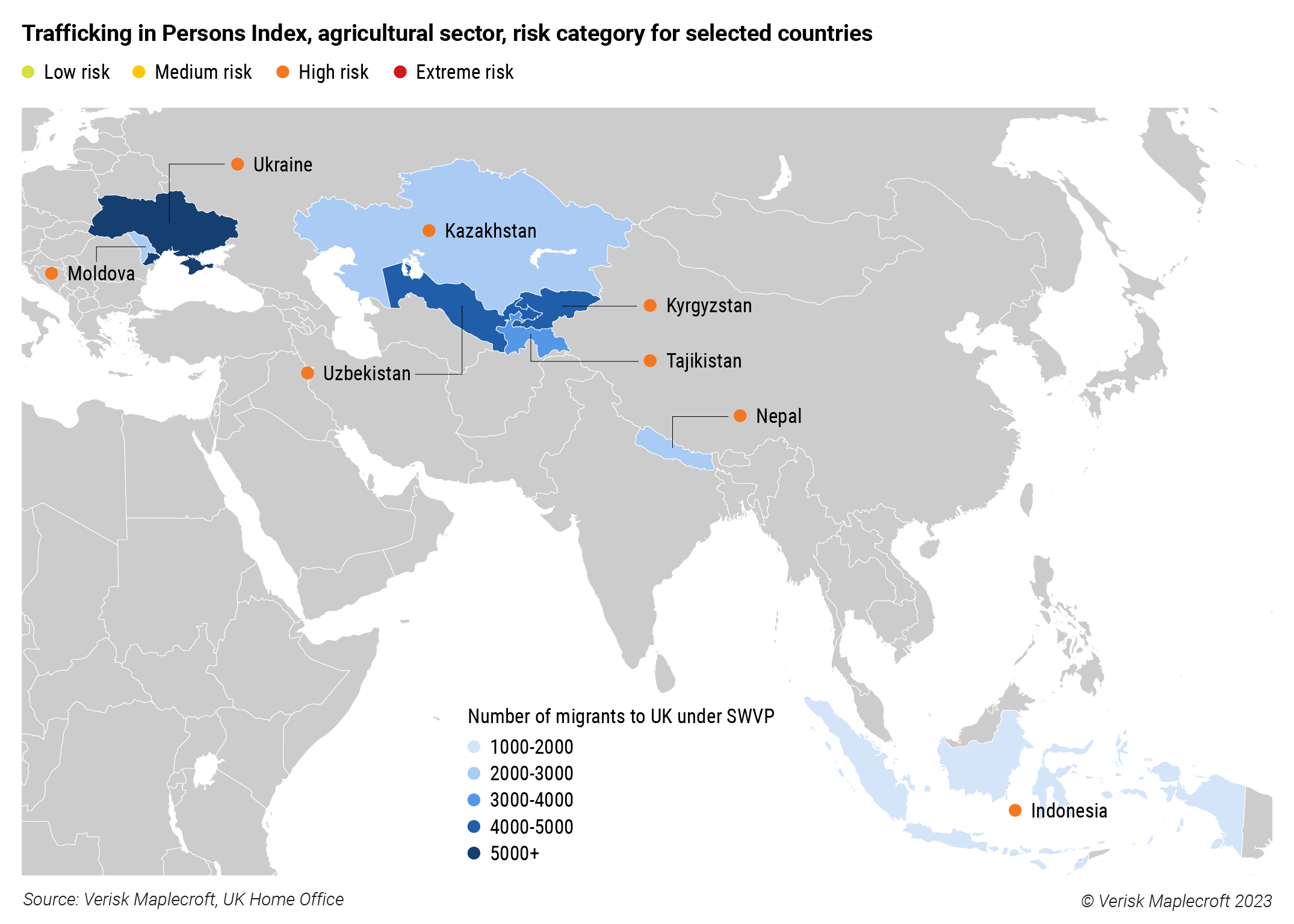

The chart below – which looks at long-term migration trends but can serve as a proxy for a trend also observed in short-term employment – illustrates a shift in the countries of origin of migrants in the UK after Brexit. In 2022, about 85% of SWVP visas were allocated to citizens from eight countries, most of which are in Central and Southeast Asia.

Figure 2: The UK has seen a sharp rise in non-EU immigration post-Brexit

In all these primary sourcing countries, the agriculture industry scores as high risk on our Trafficking in Persons Index, according to data from our Industry Risk Analytics dataset. The UK’s rapid shift from sourcing seasonal workers from the EU to less regulated countries of origin – without establishing oversight or collaboration mechanisms with recruitment agencies on the ground – has increased forced labour risks among recruits, exposing UK food retailers to human rights violations within their supply chains.

Bonded labour and its repercussions

Indeed, practices such as bonded labour have been well documented in the context of the SWVP. Bonded labour, sometimes referred to as debt bondage, usually involves a situation in which a worker is required to work for an employer to pay off a debt, or to take on debt to pay recruitment fees to access work.

A significant proportion of workers who entered the UK on a SWVP visa have reported being charged up to £5,000 in recruitment fees – which are illegal in the UK but remain prevalent in many countries of recruitment – tying workers into debts which they cannot repay in the absence of work. This limits an individual’s ability to complain about their working conditions even if they fall victim to serious labour rights violations. Other forms of exploitation and deception include contract substitution and harsh working environments, which the worker has neither freely chosen nor can freely leave.

The vulnerability of workers in these situations is further exacerbated by their living arrangements and weak contractual protections. Practically all seasonal migrant workers in the UK live in employer-provided accommodation; if they lose their job, they will also lose their home. Although the law mandates that contracts should guarantee at least 32 hours of paid employment each week, zero-hour contracts remain common practice, and workers face the constant threat of dismissal or reduced hours if they do not work quickly enough. Their debt prevents them from leaving and seeking work elsewhere. Finally, many seasonal migrants have reported being refused transfers to other farms or employers, meaning they are forced to continue to work in poor conditions to pay off their debts.

The Home Office undertook 25 farm visits between February 2021 and 2022 and published 19 reports, eight of which identified ‘significant welfare issues’ such as workers receiving incorrect pay, living in unsafe accommodation, or being obstructed from accessing healthcare. According to an investigation carried out by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, none of these allegations were investigated further by the Home Office, scheme operators, or any other institution. Overall, there is a lack of clarity as to how responsibilities are divided between the Home Office, other departments, local authorities, and the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA), which undermines oversight and enforcement of labour rights protections for seasonal workers.

What does this mean for UK food retailers and farmers?

Despite the introduction of the SWVP, farmers in the UK still experienced significant seasonal worker shortages in the summer of 2022, making labour rights violations, such as unpaid overtime, more likely as workers were pushed to make up the shortfall. Reports of violations subsequently led investors to pressure retailers to eliminate the risk of exploitation within their supply chains. In response, the recruitment companies licensed to bring in seasonal workers have announced they will stop hiring from Nepal and other high risk source countries – bringing back the issue of worker shortages.

Seasonal worker shortages are also hurting UK food retailers, as less produce is available for them to buy. However, if the government continues to increase the number of seasonal worker visas without bolstering its oversight mechanisms, food retailers face a growing risk of human rights abuses contaminating their supply chains. This has already prompted large retail chains to review their modern slavery governance and procedures, which should be a key next step for UK-based food companies.

As it stands, there is no indication that the situation for migrant workers in the UK will improve in the short-term. With the latest polls pointing to a Labour victory at the next general election, the party’s stance on migration could be key to determining how the issue develops in the coming years.

In the meantime, companies operating in and sourcing from the UK should adopt a more collaborative approach to sourcing, strengthen their supplier oversight mechanisms and engagement, and rework contracting terms to ensure they promote fair working conditions.