Human rights - 5 risks to watch

The Trendline

by Dr. James Sinclair and Victoria Gama and Capucine May and Kristina Smith and Ni'Mat Raheem-Parry and Stephanie Valle and Russ Brown and Jess Middleton,

In 2024, businesses will be subject to more stringent Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence (HREDD) laws, amid a global slowdown in human rights progress. This paradoxical dynamic exposes companies to legal, reputational, and operational challenges, as they attempt to navigate the complex intersection of environmental responsibility, respect for human rights, legal compliance and commercial considerations.

Freedom of speech and right to assembly under spotlight as key elections loom

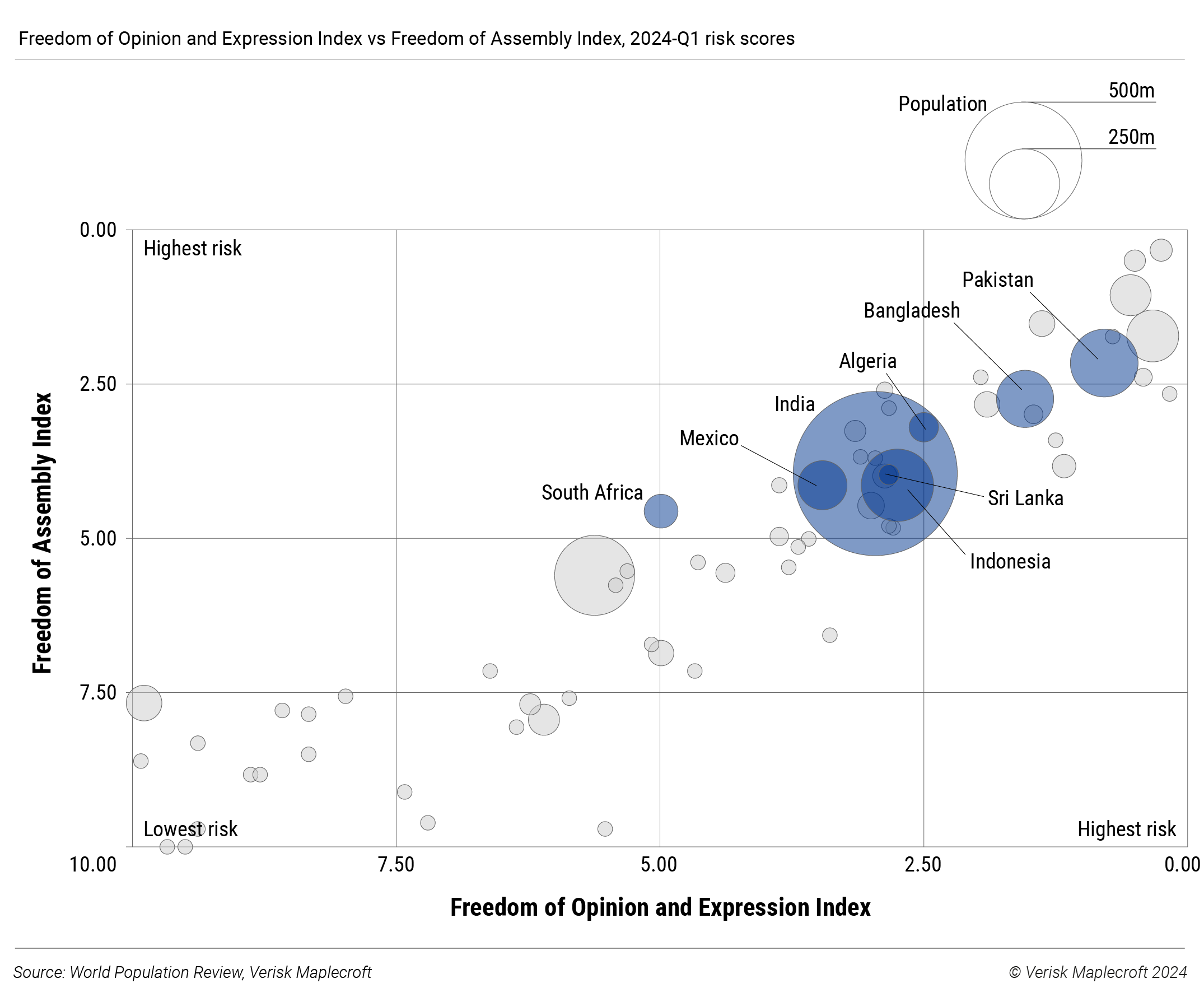

At least 64 countries will head to the polls in 2024, in what is set to be the biggest election year in history. The outcome of these elections could have a significant impact on the human rights landscape for years to come, with populist leaders and nationalist parties likely to make gains. These electoral processes may also shine a light on civil and political rights risks in several major economies.

Our data shows that half (32) of the countries holding votes this year are rated high or very high risk on both our Freedom of Assembly and Freedom of Opinion and Expression indices. These include several of the world’s largest democracies, such as India, Indonesia and Mexico. How fairly and peacefully polls across the world are conducted will tell us much about the health of global democracy and respect for human rights.

In countries with a weaker human rights profile, election-related protests and associated crackdowns could expose businesses to allegations of inadvertent complicity with violence at the hands of security forces. Indeed, data from our predictive Civil Unrest Index shows that 46 of the 64 countries holding votes this year face elevated protest risks over the next 12 months. Some 26 of these also fall within the two highest risk categories of our Security Forces and Human Rights Index, which measures the risk of association with human rights violations committed by public and private security forces.

Energy transition mired by social license to operate risks

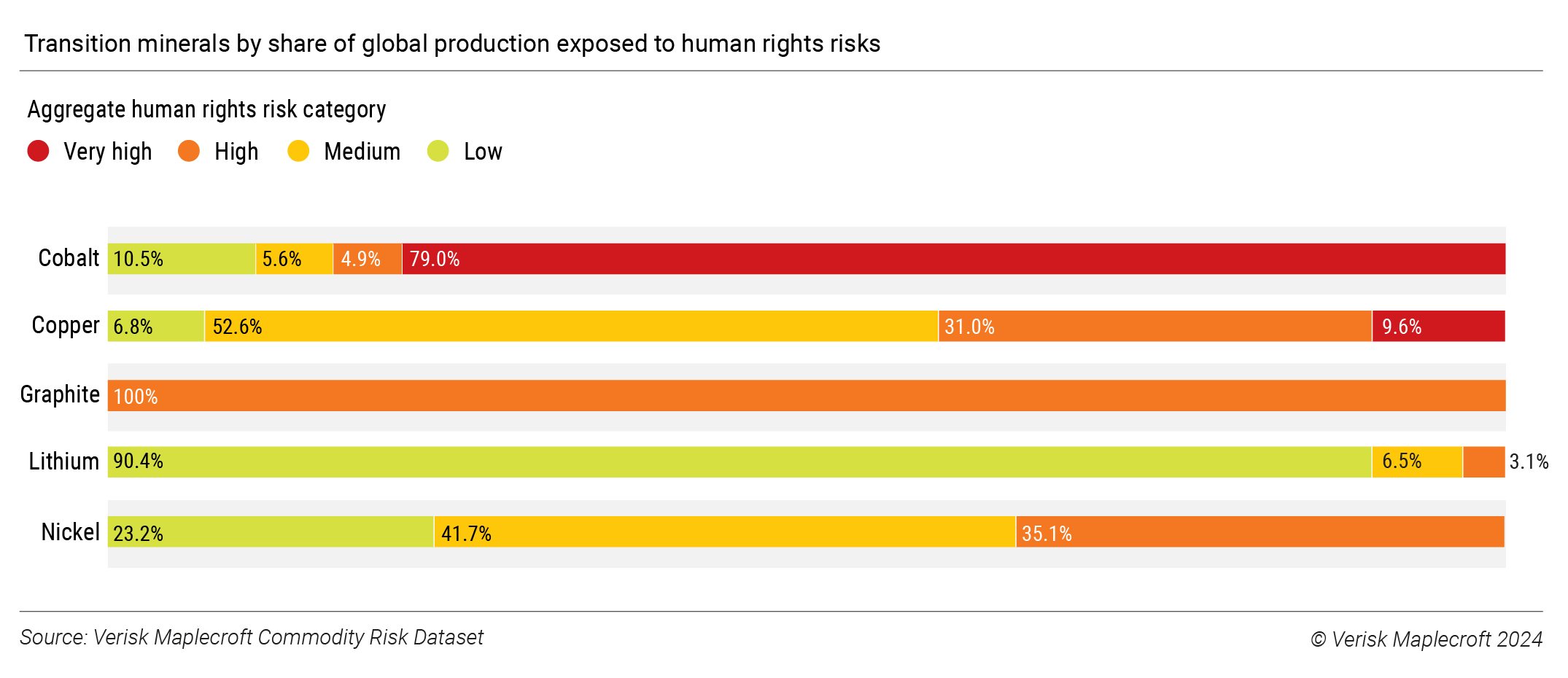

Companies central to the energy transition face a dilemma in the year ahead. There is a push by key markets, such as the US, Canada and the EU, to strengthen supply chains for minerals that are critical to green technologies, but this can mean sourcing from countries where human rights risks are elevated. Against the backdrop of increasingly stringent HREDD legal obligations, corporate supply chains are facing an increasingly complex set of challenges.

Our data shows that over half of the top 10 sourcing countries for energy transition minerals – such as cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium and nickel – are rated high risk for human rights issues in supply chains. Drilling down further shows that a significant share of critical mineral production takes place in jurisdictions facing heightened human rights risks, as shown by the chart below. These issues span from labour rights incidents at mining or processing sites, to impacts on local communities stemming from water use, pollution and biodiversity loss. As such, companies must ensure their sustainable sourcing strategies are robust and mindful of local community rights.

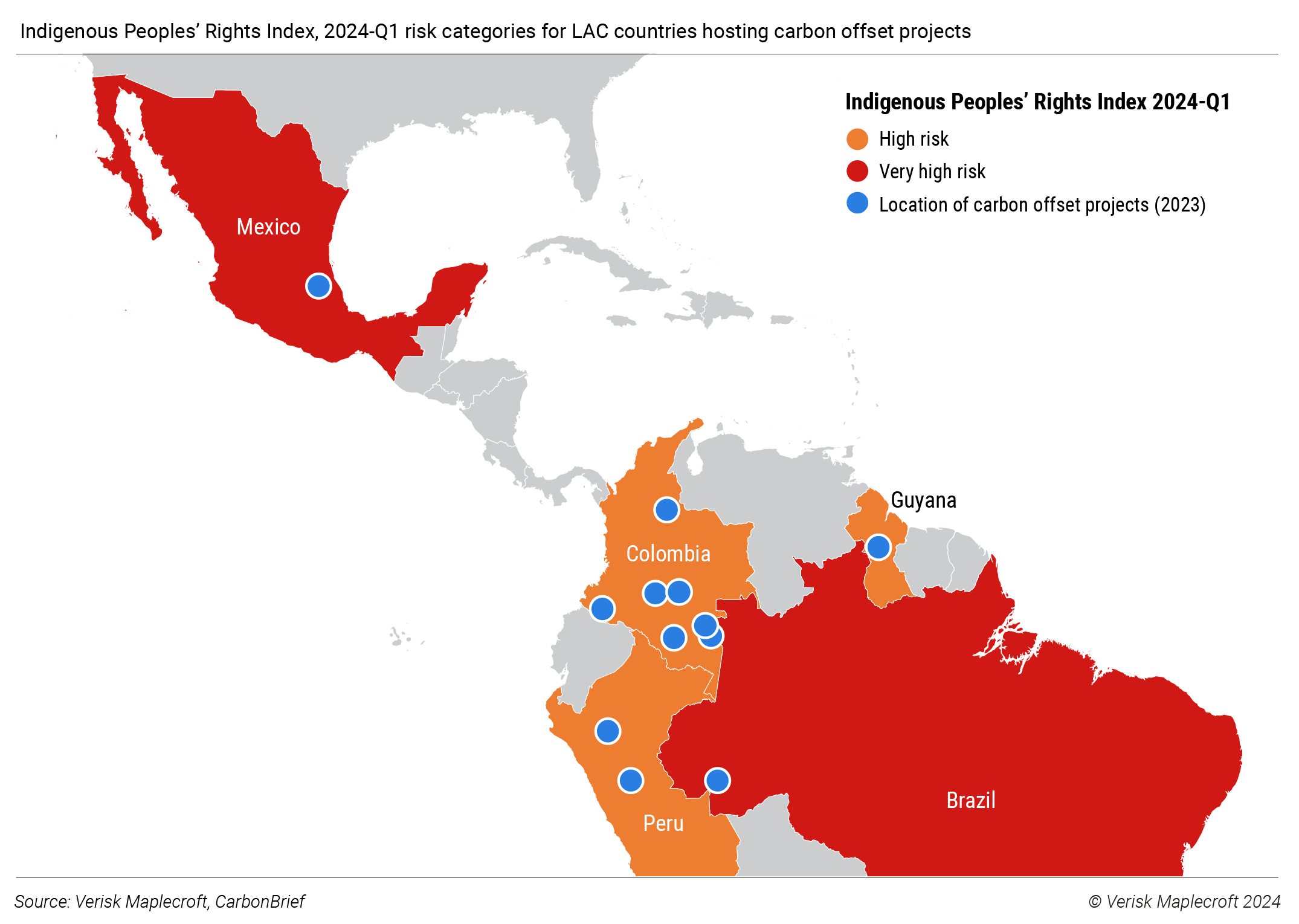

Carbon credits a new battlefront for indigenous communities

Private investors and businesses are increasingly purchasing carbon credits to offset emissions, but these mechanisms can, and do, impact the rights of indigenous communities. Carbon markets are likely to feature prominently on the COP29 agenda in November, as the global demand for voluntary offsets is set to increase 100-fold by 2050. However, carbon credits often rely on forest offsetting schemes that require mass purchases of land. This means they can threaten community land rights and indigenous groups’ access to ancestral lands.

Countries in the Global South, where most carbon-offset projects are based – including the DR Congo, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Kenya, Mexico, Malaysia and Indonesia – score as high or very high risk on our Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Index. With these risks to vulnerable groups set to rise, carbon finance stakeholders are going to have to adopt a rights-based approach to mitigate impacts on indigenous communities through a free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) process. Failure to do so could create social impacts when trying to offset carbon footprints.

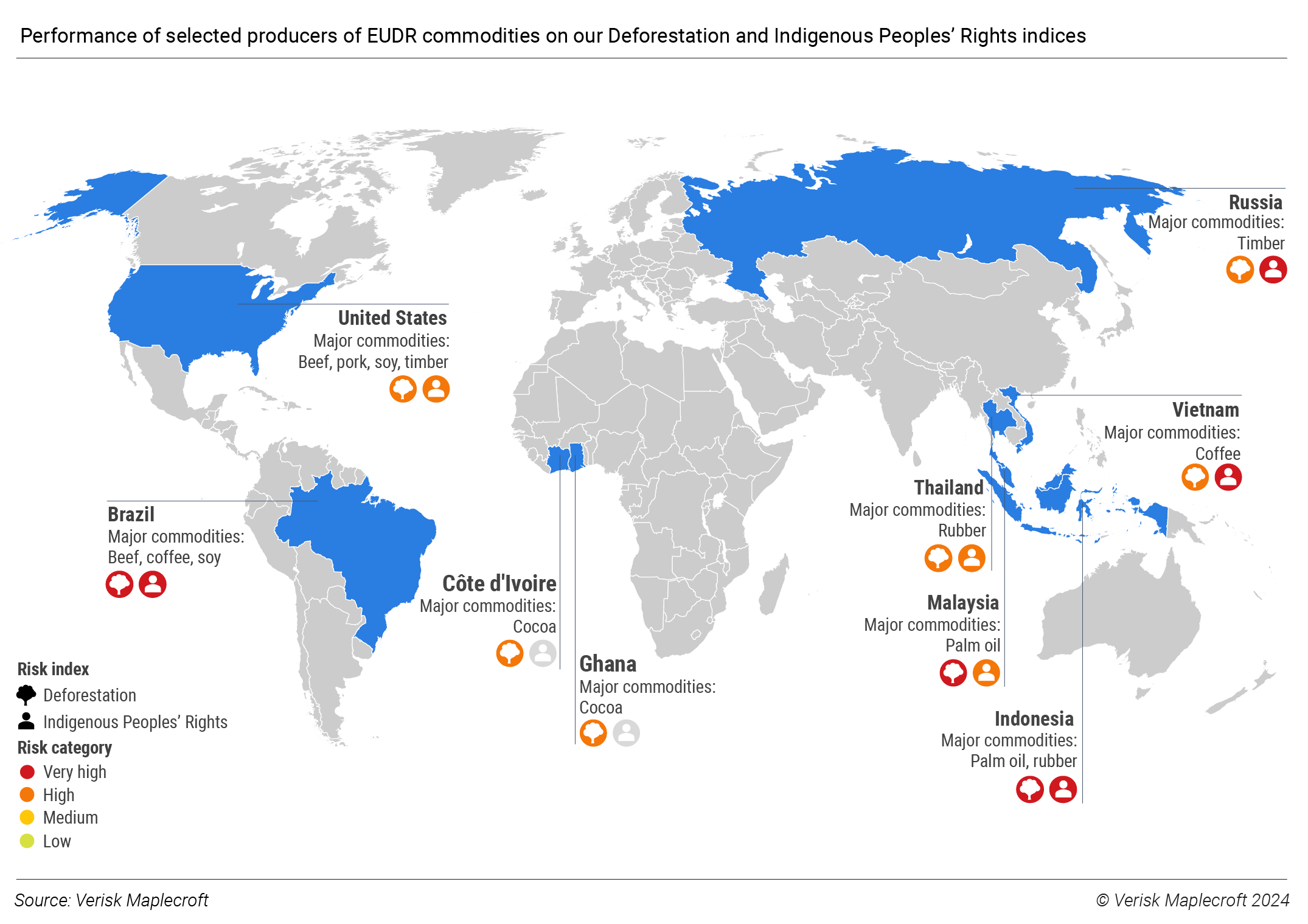

Is the EU Deforestation Regulation a game changer for supply chains?

The human rights performance of the agricultural and consumer goods sectors is set to come under greater scrutiny when due diligence obligations under the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) begin on 30 December 2024. The scope of the EUDR is huge, covering around EUR126 billion, or 4.2% of all EU imports (based on 2022 figures). Companies are going to have to get ahead of the legislation or they could face hefty fines and a temporary prohibition from dealing in the EU.

The aim is to guarantee that consumer products imported into the EU do not contribute to deforestation, forest degradation, or impact the rights of indigenous peoples. This means the EUDR will require the certification of beef, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soya and wood as deforestation free, as well as products derived from these commodities. Significantly, the regulations are retroactive with certification having to cover the period since 31 December 2020.

With several of the world’s top producers of the listed commodities categorised as high or very high risk on our Deforestation and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights indices, identifying and acting on exposure to these issues is an immediate concern for companies in the affected sectors.

Stalling CSDDD progress threatens further fragmentation of the due diligence landscape

There is currently a piecemeal approach to corporate sustainability due diligence and reporting requirements within the EU. Laws vary across countries and judges are interpreting obligations in different ways. This leaves companies uncertain about exactly what is expected of them. The EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) was designed to create a level playing field across the union (and beyond, with global supply chains also in scope). However, last minute concerns raised by the German government have thrown its progress into question.

Ironically, Germany is currently the only country in Europe with a detailed corporate sustainability law (the LkSG). If it doesn’t support the CSDDD to reduce ‘red tape’, it will impose obligations on German companies that are not shared by the rest of Europe.

In the absence of a level playing field, we expect an increase in corporate sustainability litigation as courts are forced to fill the gap left by the legislators. This will result in further fragmentation of the due diligence landscape, an outcome that companies will be keen to avoid, which is why so many are publicly backing the CSDDD.