Political instability is on the rise globally as governments increasingly struggle to maintain authority and implement their policy agendas, according to our latest research.

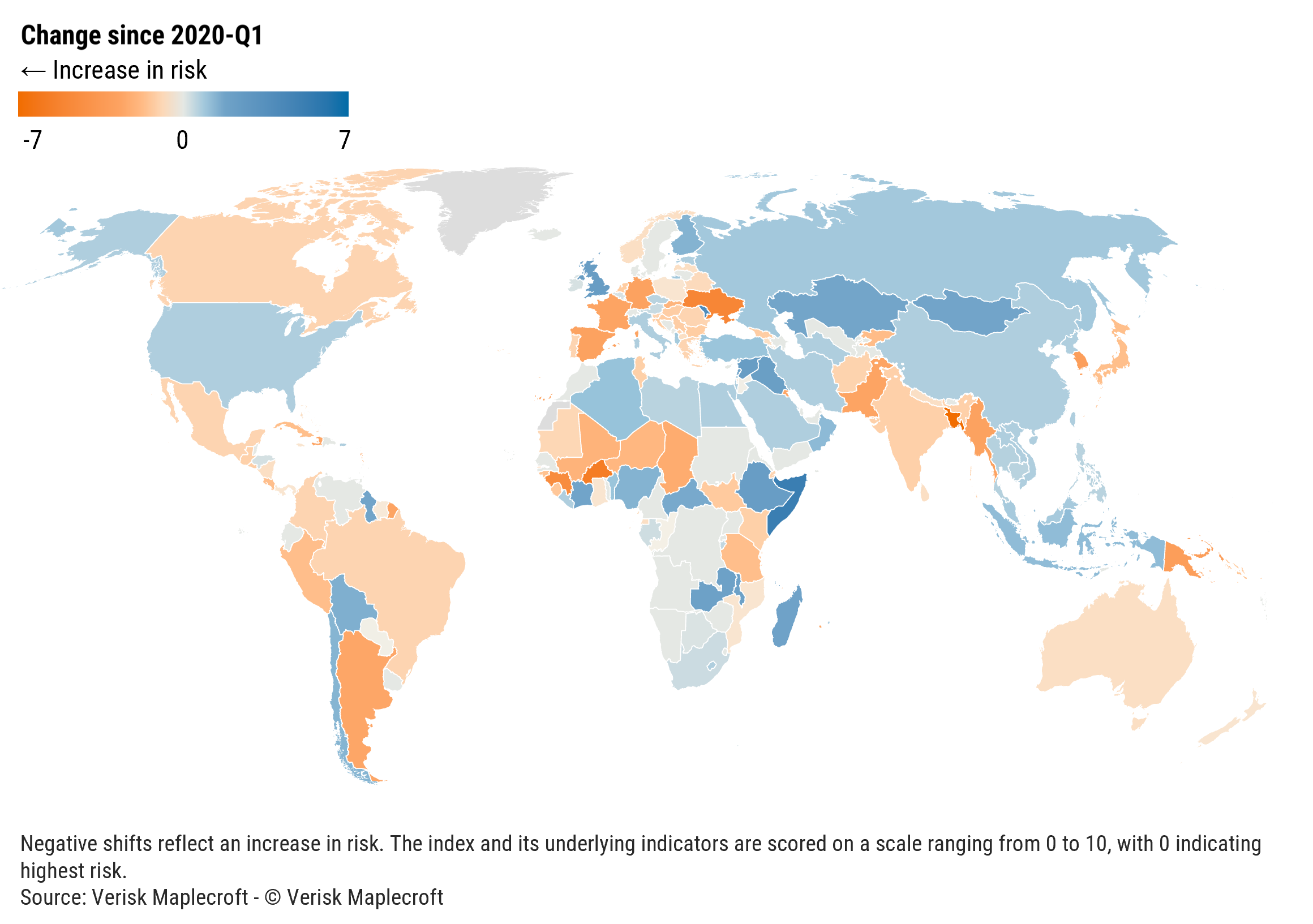

Our Challenges to Government Authority Index (CGA), which tracks a range of threats to government authority and policymaking in 198 jurisdictions, shows that risks have intensified in 82 countries since the beginning of 2020, compared to 61 that have seen a notable improvement. These shifts underscore growing volatility in the political risk landscape, heightened by rising global trade tensions, with direct implications for business environments and policy predictability.

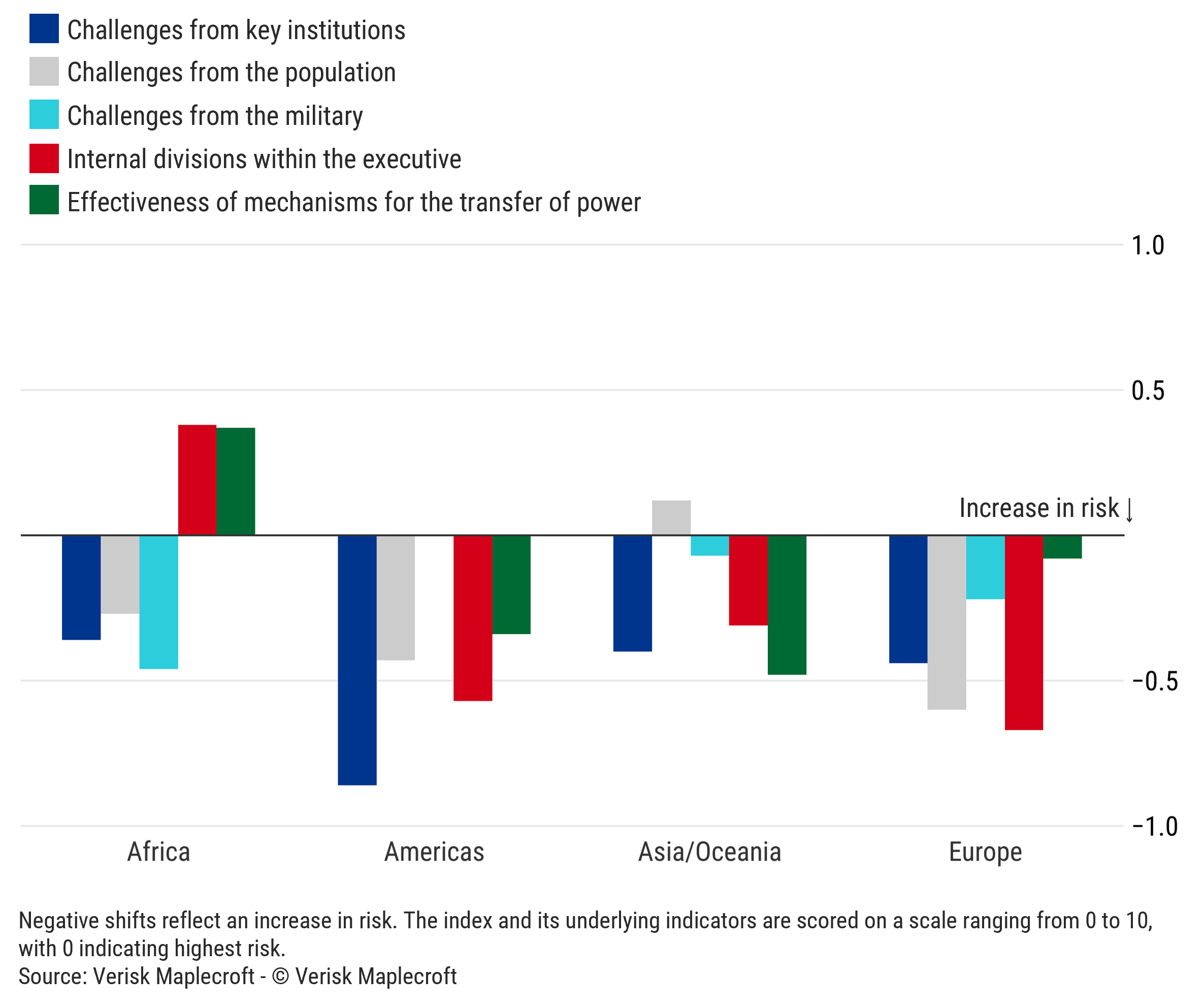

While challenges are rising worldwide, Europe, the Americas and Asia have seen particularly negative trends, with governments increasingly constrained by weak mandates, internal divisions and rising public discontent. Sub-Saharan Africa stands as the highest-risk region globally, where entrenched instability in parts of the continent continues to undermine effective governance.

The drivers vary in type and severity, ranging from internal disputes within ruling coalitions and legislative gridlock to mass protests and, in extreme cases, direct threats stemming from the military and armed conflict.

Key institutions exerting pressure on governments

The data shows that governments across the world have faced a rising number of challenges from key institutions, including the legislature and the judiciary. While checks and balances are essential to the democratic process, persistent institutional challenges can also stall political agendas, erode trust in institutions and inject uncertainty into the business environment. Disruptive opposition and court challenges present a higher risk when executives are weakened or act contrary to constitutional norms in a bid to maintain power.

Take South Korea, which has seen one of the sharpest declines on the index since 2020. The country entered a political crisis in December 2024 when former president Yoon Suk Yeol briefly imposed martial law in an attempt to subvert civilian rule, a move that led to his suspension, impeachment and eventual ousting by the courts. The turmoil triggered by Yoon unleashed months of political drama in which constitutional norms were under heavy strain, and also sparked over 1,000 protests by both anti- and pro-Yoon groups.

France serves as another example of institutional challenges translating into risks for businesses. Political instability has deepened in the country since mid-2024, when snap elections produced a deeply divided National Assembly. Successive minority governments have struggled to pass policy, including the 2025 budget, amid opposition from left- and right-wing MPs alike. Although the budget eventually passed, the government’s limited room for manoeuvre will hamper further economic reforms. The deadlock also raises the prospect of another snap election later this year.

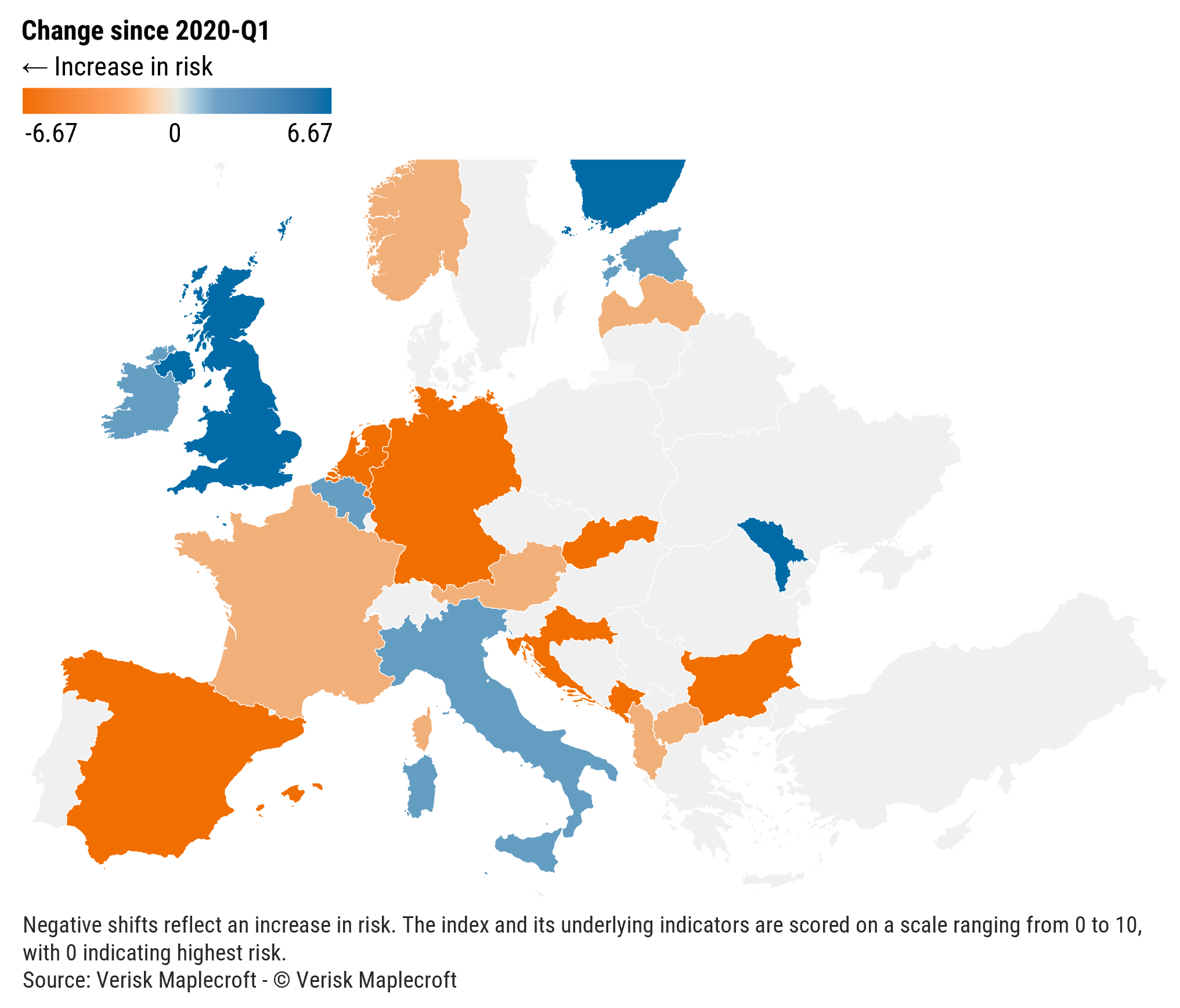

Government infighting undermining political stability in Europe

Internal government divisions are another key factor undermining executive authority globally. Infighting and fractures within ideologically strained coalitions have contributed to growing policy paralysis and, in some cases, outright government collapse. This trend is most acute in Europe, where mainstream parties are losing ground amid simmering anti-incumbency sentiment. This has pushed many into broad but fragile coalitions that are struggling to deliver on key policy issues, creating a more unpredictable environment for businesses.

In Spain, for example, the government’s difficult internal relations and reliance on regionalist parties continues to hamper policymaking, with Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez struggling to pass a budget for a second consecutive year. Persistent tensions between coalition partners in the Netherlands, particularly over migration, have similarly impacted policy cohesion and cast doubt on the government’s longevity.

Germany’s decline on the index reflects the collapse of the ‘traffic-light’ coalition in November 2024 following disputes over fiscal reform. While a recently agreed coalition deal between the centre-right CDU and the centre-left SPD signals an imminent return to some stability, the rapid reorganisation of the country’s spending priorities is set to serve as an early test of intra-coalition unity.

Italy and the UK have bucked the regional trend, underpinned by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s stable right-wing majority in Italy and the strong mandate secured by Labour in the UK’s 2024 general election.

Popular unrest is a risk multiplier

Government infighting and challenges from key institutions are often accompanied and intensified by civil unrest, as seen in South Korea. Unpopular governments facing sustained protests or strikes are more likely to implement populist policies, which are often rushed and adopted without proper consultation. Alternatively, they may respond to challenges from other institutions by enacting unpopular reforms, stoking public resentment. This exposes businesses to uncertainty, such as unexpected tax rises and regulatory changes. At the same time, such policies are unlikely to address popular grievances over the longer-term, creating the conditions for further unrest.

Bangladesh is a prime example of government challenges coalescing over time, leading to the executive’s ultimate demise. Mass student-led protests triggered the collapse of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government in August 2024, ushering in a period of major political instability. Bangladesh’s decline on the CGA is the steepest recorded globally since 2020.

In Argentina, President Milei’s austerity push has sparked strikes and disruptive protests, albeit fewer than initially expected. Tensions are likely to rise in the run-up to the October mid-terms, further straining a policy agenda already hindered by the government’s lack of a congressional majority – something even strong electoral support will not fundamentally change.

Governance challenges run highest in conflict-affected states

Unsurprisingly, the worst-performing countries on the CGA are primarily those impacted by armed conflict. In Africa’s 'conflict corridor', for example, widespread insurgencies and rifts between civilian governments and military leaders have severely undermined state authority, driving scores on the index downward.

Burkina Faso has recorded the sharpest decline in the region, with militant groups now exerting control over more than half the country’s territory. A series of coups and coup attempts since 2022 have further undermined executive authority.

In Sudan, which ranks as the worst performing country globally, the ongoing civil war has left state institutions paralysed, displaced millions and created a governance vacuum across much of the country. Looking beyond Africa, similar trends are observable in Myanmar and Yemen, where the instability brought about by protracted civil wars has placed both countries within the 10 highest-risk jurisdictions globally.

Threats to government authority set to remain elevated

There is little indication that the challenges facing governments globally will ease any time soon. Indeed, the economic and political fallout triggered by rapidly escalating global trade tensions will likely serve as a major test of government unity and effectiveness in the months ahead. For businesses, integrating cutting-edge risk data and expert insight into strategies and decision-making processes will be key to navigating the resulting volatility.