Hungary, Israel, Poland and Turkey continue their democratic backslide

by Hamish Kinnear,

Our data shows that democratic governance is under pressure globally, but part of that story is the rise of illiberal democracy. While there is no precise definition for an illiberal democracy, typically they hold competitive elections, yet stage them under unfair conditions, and are led by figures who project a strongman image.

By looking at five countries – Hungary, India, Israel, Poland and Turkey – that have registered relevant changes on our indices, we have identified four broad trends that connect jurisdictions where illiberal democracy is in the ascendant. These trends matter for foreign investors, who will face heightened ESG risks and must deal with institutions like the judiciary that lack independence from the government.

1. The ballot box remains relevant, but isn’t the sole factor in democratic governance

In an illiberal democracy, the vote matters. As a source of legitimacy for leaders it is unrivalled, as a majority in presidential vote share or parliamentary seats gives licence to the ruling party or leader to claim a direct mandate from the people. This is particularly useful when illiberal leaders take on independent institutions like the judiciary or the media or crack down on minority groups in the ‘interests’ of the majority.

Outright vote rigging risks ruining this illusion, requiring leaders in illiberal democracies to use other means to tilt the scales in their favour and preside over free, but not fair, elections. Election observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation (OSCE), for example, described the most recent elections in Turkey and Hungary as competitive but highlighted the lack of a level playing field that gave the incumbents unfair advantages.

The fact that the competitiveness of elections is not the sole factor in the health of a democracy is reflected in the construction of our Democratic Governance Index (DGI). Countries like Turkey and Hungary, where elections are competitive, are nonetheless rated as medium and high risk respectively in part due to poor protections for press freedom (see 2) and weak judicial independence (see 3).

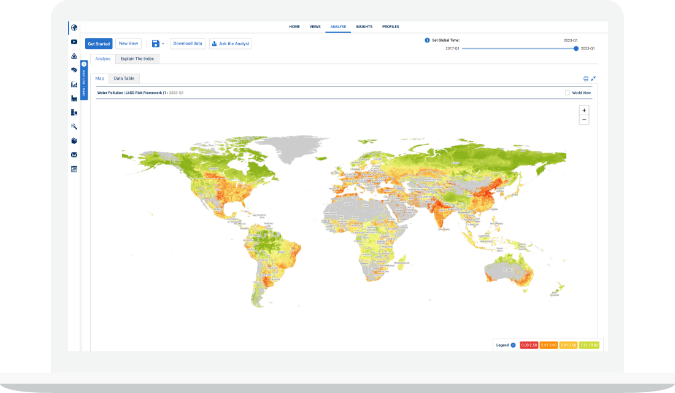

Figure 1: Competitive elections are not the sole measure of the health of democratic governance

2. Restrictions on independent media

An obvious yet critical method to tilting the scales in elections is having a pliant media behind you. This was a crucial factor in President Erdogan’s election victory, with NGO Reporters Without Borders estimating that 90% of Turkish media has a pro-Erdogan slant. Erdogan’s focus on nationalism and identity politics drowned out opposition criticism of his handling of the economy.

Crackdowns on freedom of expression are more recent in countries with increasingly illiberal tendencies. India, for example, has seen what we classify as a significant deterioration in its score on our Freedom of Opinion and Expression Index since Prime Minister Narendra Modi was elected for his second term in May 2019. In part, this is a result of Indian authorities increasingly resorting to security and defamation laws to silence critical voices.

3. Curbs to judicial independence

The separation of powers is a fundamental safeguard for a functioning democracy, as it places limits on executive or legislative authority to, for example, push through anti-constitutional laws. In Poland, reforms pushed through by the socially conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party had a destructive impact on judicial independence, driving the biggest single global decline on our Judicial Independence Index since 2018-Q2.

A similar effort to reform the judiciary is at the heart of recent political turmoil in Israel. The right-wing coalition led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu wants to give Israel’s parliament – the Knesset – the power to overrule the decisions of the highest court by a simple majority. Were the reforms to pass, Israel’s fiercely independent judiciary would be weakened and the Netanyahu-led government able to pass laws that shore up its right-wing base.

Figure 2: Threats to independent media, judicial independence and minority rights undermining democracy

4. Ruling in the interests of the majority

The most politically successful of the illiberal democrats are adept at finding their electoral base and then doubling down again and again to ensure its loyalty.

In Turkey, President Erdogan’s combination of nationalism and social conservatism has proven remarkably durable. Despite the economy being in dire straits and a rising cost of living, Erdogan’s enduring appeal meant he took 52.2% of the vote in the 2023 presidential elections, barely a shift from the 52.6% that he took in the 2018 elections. Similarly, India’s Modi managed to secure an increased vote share and share of seats in the 2019 elections in part by appealing to his Hindu nationalist base, undermining India’s historically pluralistic democracy.

5. All the above creating headaches for foreign investors

There are two key reasons why the above matters for foreign investors and companies looking to invest or operate in illiberal democracies.

The first is that attacks on judicial independence, freedom of expression and minority rights are in and of themselves an ESG risk. Institutional investors looking to adhere to ESG principles face heightened challenges when looking at illiberal democracies.

The second is that ostensibly independent institutions that have been co-opted by illiberal governments can create financial, operational, and legal difficulties for foreign companies. A court that has been stacked with pro-government judges is, for example, less likely to be fair in a trial that pits a foreign company against a local company favoured by the government. Similarly, an ostensibly independent central bank taking its cues from a president committed to unorthodox economic views rarely creates favourable conditions for investors.