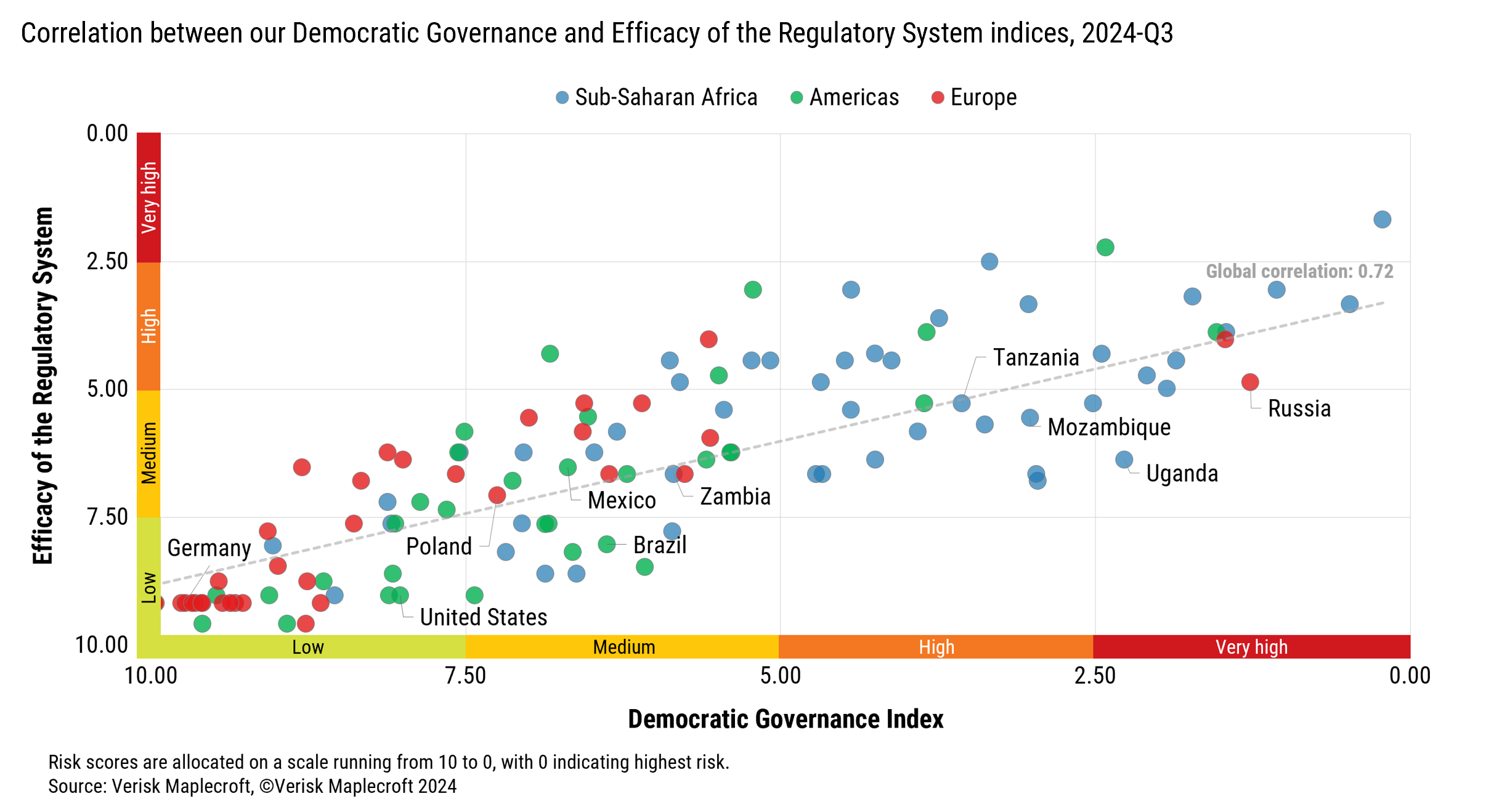

In the last four years, democracy has suffered setbacks in over 50% of countries, according to the latest edition of our Democratic Governance Index (DGI). Weakening electoral processes, institutional decline and a rising number of coups have all played their part, but the impacts are extending beyond electorates and into business risks on the ground. Drawing on our Political Risk Dataset, we have found a strong correlation between declining democracy and worsening regulatory environments, which is leaving multinational businesses exposed to greater unpredictability in an ever-increasing number of countries. The trend is strongest in the Americas and Africa but can be seen across many investment locations around the world.

Democratic mechanisms are designed to reduce the risk of political instability by strengthening popular trust in the system. They also aim to increase transparency in government decision-making and reduce regulatory uncertainty and volatility to stimulate investment. Policy implementation that has minimal input from external experts and business often results in cumbersome regulatory systems, but it can also change the rules of the game to benefit or harm particular stakeholders.

Today, roughly 30% of the world’s GDP is concentrated in countries categorised as high or very high risk on our Democratic Governance Index. Given the relationship between the two issues, it is not surprising that two-thirds of chief economists surveyed by the World Economic Forum for its May 2024 outlook cited the regulatory environment as a key driver of decision-making in the year ahead.

Figure 1: Many countries have experienced a democratic decline in the last four years

Democratic credentials determine the effectiveness of regulations in the Americas, Africa and Europe

The Americas and Africa account for about half of the countries that have experienced a significant deterioration on our Democratic Governance Index since 2020-Q3. In the Americas, this includes the region’s largest economies, the United States, Mexico and Brazil. A common significant driver is the increasing politicisation of the judiciary and the erosion of the separation of powers, which can create uncertainty for specific industries.

For the US, this was felt keenly by the energy sector when the Supreme Court repeatedly intervened on Obama-era climate policies and through the removal of regulations by executive order at the onset of the Trump administration. While the US remains a low risk jurisdiction on our Efficacy of the Regulatory Environment Index, it has lost ground over recent years and further regulatory unpredictability cannot be ruled out following the presidential election in November. Mexico’s mining industry has also witnessed upheaval, with authorities in some regions applying the 2023 mining law retroactively to restrict exploration. The enforcement of these regulations has been challenged in the courts, but with questions over judicial independence, legal disputes will be time consuming and expensive. We expect the situation to worsen under the new president.

Challenges to democracy in Africa, a key hub for mining and energy, have been on the rise following the recent wave of coups in the Sahel and the deterioration of electoral standards across a broader range of countries. This has resulted in a decrease in the transparency of regulations in some of these economies. Uganda’s democratic credentials deteriorated following the 2021 general election, which was marred by widespread violence and repression of dissent. The county’s score on our Efficacy of the Regulatory System Index has declined since then as the independence of regulatory bodies all but disappeared. International oil companies have long complained about politically connected businesses receiving preferential treatment and taxes being applied retroactively.

Conversely, positive democratic gains have had a significant impact on the business environment. Zambia’s score on our Efficacy of the Regulatory System Index improved considerably in 2022-Q2, one year after the 2021 presidential election, in which the then-opposition won the ballot. The new government since ended years of regulatory uncertainty and resource nationalist policies in the mining sector, boosting foreign investment in the sector by USD7 billion in just two years.

Countries in the European Union are among the best performing on both indices, indicating that their tried and tested democracies have contributed to securing greater regulatory transparency and predictability. However, growing disenchantment with globalisation has fed political polarisation at home, increasing support for far-right leaders. With important polls occurring across many of these economies business should prepare for a likely increase in regulatory uncertainty over the coming four-to-six years.

With the strengthening of the far-right in the European Parliament, we expect trade and industrial policy to become more protectionist – although the EU is unlikely to introduce sweeping US-style import tariffs. On the flip side, environmental regulations, especially those related to agriculture, are likely to be revised to reduce costs for businesses.

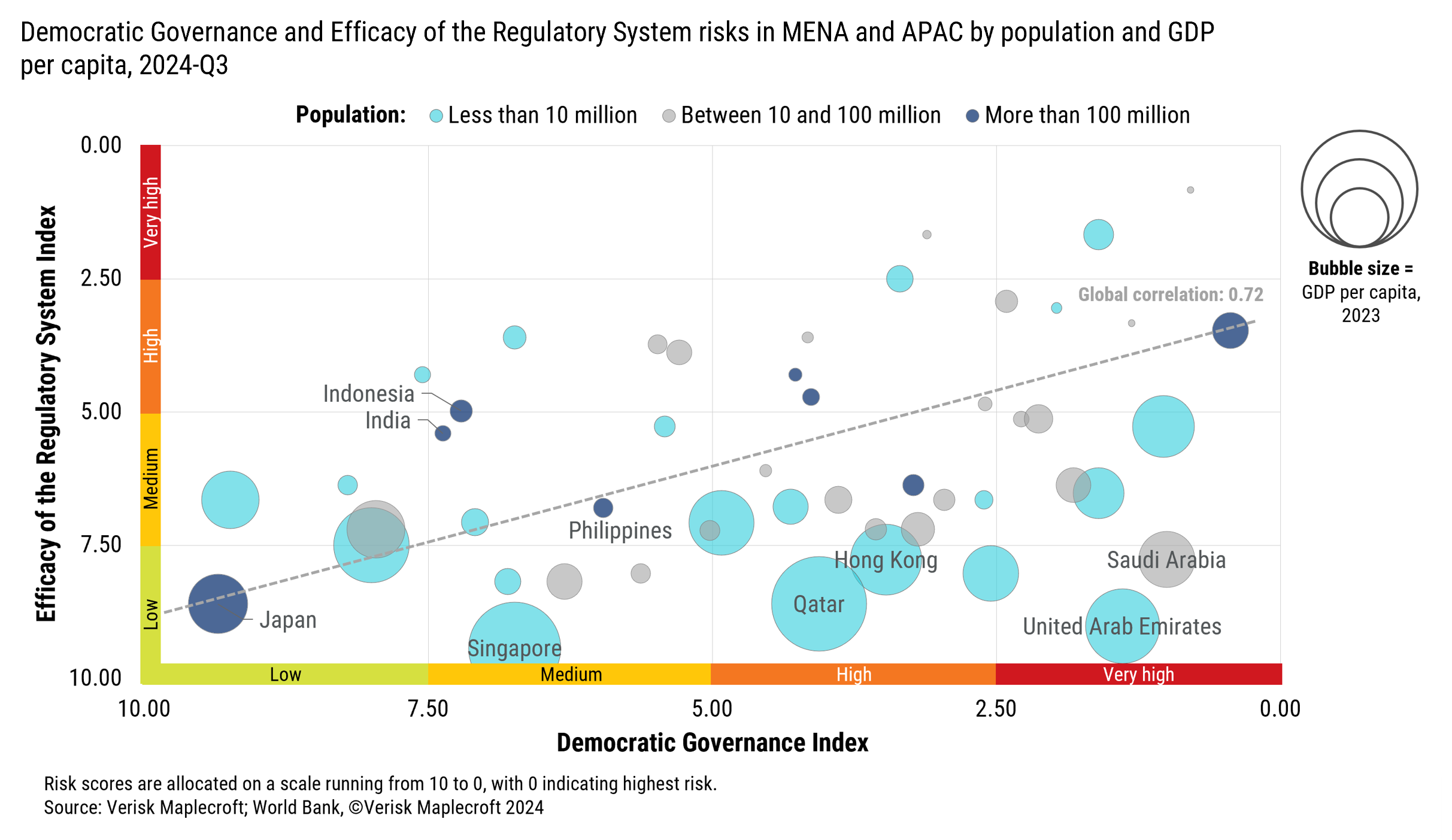

MENA and APAC appear to buck the trend, but in fact present a more complex landscape

The link between democratic credentials and the efficacy of regulatory systems is less consistent in MENA, where some countries with poor democratic credentials present some of the strongest regulatory systems. In Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Qatar, where the separation of powers is less defined, there is a degree of political interference in the private sector. But current policies are in place to encourage investment, it is clear which regulations are in force, and foreign investors generally enjoy a level of predictability. One variable that explains why these countries differ from other less liberal countries is GDP per capita. Most non-democratic countries with a business-friendly regulatory environment are small but rich, offering incentives to welcome foreign investment (see Figure 3).

The picture is different again in Asia, where some of the world’s largest democracies present an unpredictable business environment. India’s complex structure of federal and sub-national policymaking has undermined the transparency and efficacy of regulations, for example, stalling the implementation of business-friendly reforms to labour laws. Following the 2024 election, India has entered a new era of coalition government which will likely necessitate a more consensual approach. In Indonesia, businesses have reported that the court system often fails to resolve property and contractual disputes efficiently. Moreover, policy inconsistency, bureaucratic inefficiency and corruption undermine the effectiveness of the regulatory system.

The existence of a solid and transparent regulatory environment is not the only variable investors should consider. In the case of autocratic or authoritarian regimes, companies risk being perceived as complicit with the violation of labour rights. Indeed, 68 of the 72 countries categorised as very high or high risk on our Democratic Governance Index fall in the same categories of our labour risks composite index (see below).

Figure 4: The worst performers on our Democratic Governance Index present higher labour risks

Electoral supercycle to expose democratic shortcomings

Doing business in autocratic jurisdictions also exposes companies to operational, financial and legal risks. These include arbitrary decisions taken by the government based on their country of origin or their proximity to the regime, with the potential to force divestments or the end of operations in the more extreme cases. The lack of judicial independence negates investors’ access to impartial arbitration or courts. And while access to international forums may exist on paper, some of these regimes have repeatedly failed to recognise the rulings of institutions like the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID).

The 2024 electoral supercycle will test the state of democratic governance across the globe. Although holding elections is a key element of democratic systems, the rise of illiberal democracies shows that other factors can undermine the fairness of the electoral process. Countries across the globe are increasingly staging elections under unfair conditions to secure re-election. Although this trend can contribute to the stability of the political landscape in the short-term, our research indicates a democratic decline also exposes companies to higher regulatory risks in the medium-to-long term.