Conflict is on the rise globally and further flashpoints could be on the horizon, according to our latest data and predictive models tracking political violence and geopolitical tensions. The trend extends far beyond Ukraine and Gaza with 28 countries experiencing increases in conflict over the last three years.

The ramifications for corporates, investors and insurers are far-reaching, from security risks and trade disruption to supply chain continuity and rising risk premiums. With resilience becoming a watchword for business, organisations must ensure they are factoring the conflict into their planning and have all necessary tools at their disposal to identify, anticipate and monitor their exposure to the direct and indirect risks.

Major implications for the global economy

All continents are affected. Unpacking the data in our Conflict Intensity Index, which tracks the severity of internal and international armed conflict, reveals 28 countries, including the emerging markets of Colombia, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Thailand, have experienced a significant increase in risk since 2021. This compares to only five that have experienced a significant decrease in risk, including Afghanistan and Armenia which are still experiencing armed confrontations, albeit at lower levels than previously. The petering out of an Islamic State-led insurgency accounts for Egypt’s improving score, although it faces spillover risks from the neighbouring conflict in Gaza.

Figure 1: Conflict risks have intensified in 28 countries since 2021

Recent conflicts have had major implications for supply chains and the global economy more widely. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine led to spikes in energy and food costs as Ukrainian grain exports were cut off and Moscow’s fertilizer and energy exports upended by sanctions. The knock-on effect of a global spike in inflation had profound impacts for investors, insurers and businesses alike. One estimate claims that global inflation rose by as much as 1.8% in 2022 as a direct result of the war, and that it cost 1% of global GDP in 2023 (over USD1 trillion). Supply chains subsequently adapted to the new reality in Russia and Ukraine, only for Hamas’s 7 October attack on Israel to kick off a Middle East crisis that disrupted maritime shipping in the Red Sea from December 2023 onwards. The average cost of shipping containers more than doubled in a single month.

Our Industry Risk Dataset identifies the sectors that are most exposed. Agriculture and oil & gas sectors rank among the 10 industries most at risk from conflict globally. The other key extractive sector, metals & mining, is the third most exposed, with concentrations of precious metals and minerals in single locations often a recipe for conflict.

All three industries have faced increasing exposure to conflict events since 2020, according to data from our Industry Risk Dataset events feed, which utilises AI and data science techniques to log and classify reports from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED).

Figure 2: Key industries facing increased exposure to conflict

Conflict a symptom of fragmenting world order

To put the rising trend in context, conflict-related deaths are at a multi-decade high. Data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, the Peace Research Institute Oslo, and the methodology of Our World in Data, shows that 2022 was the deadliest year for conflict-related fatalities since 1986 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Conflict deaths at highest level since 1986

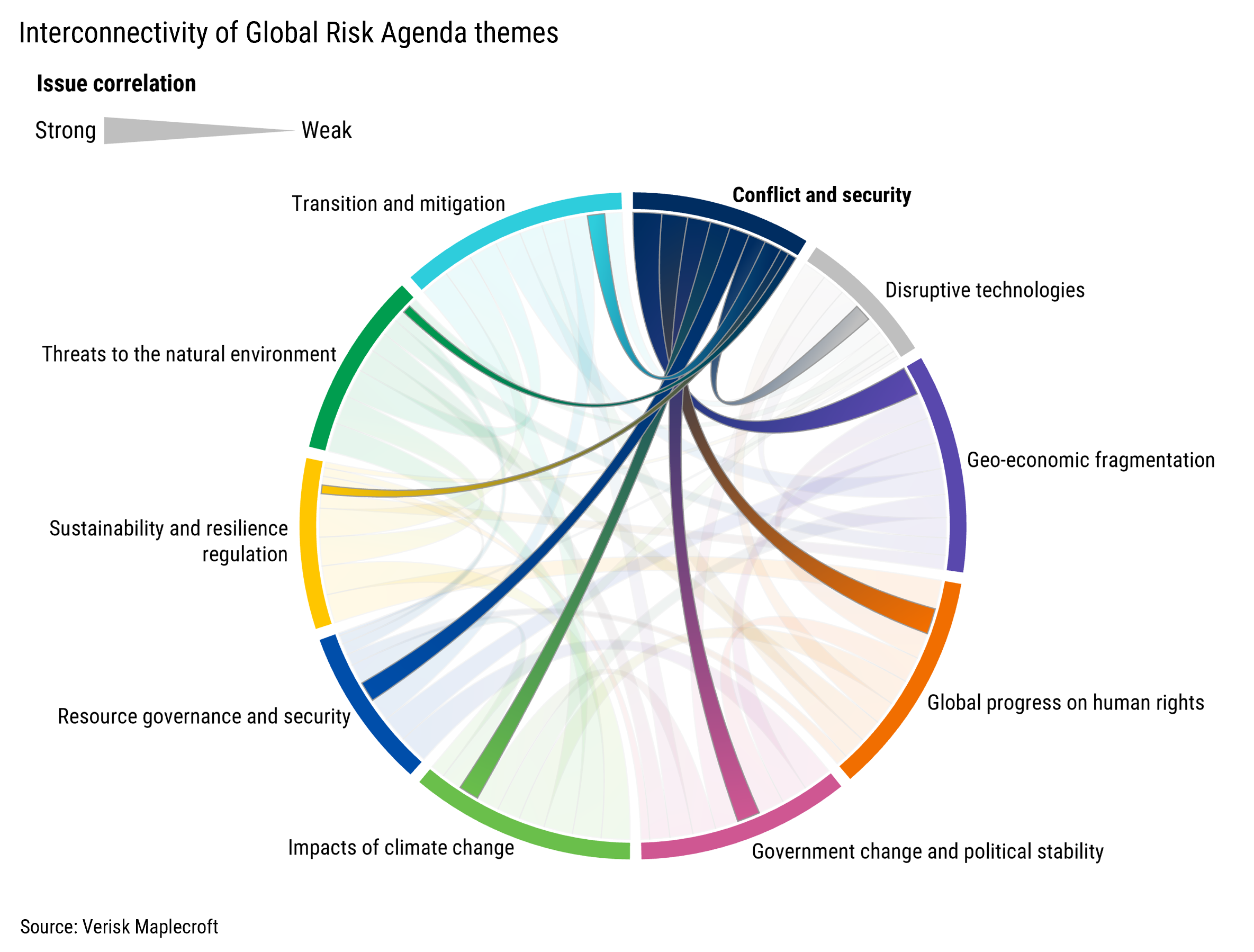

The spike in conflict deaths raises the question of whether this is a temporary blip or a definitive end to the ‘peace dividend’ – the era of relative peace that followed the conclusion of the Cold War with the fall of the Berlin wall. Two factors that suggest that raised levels of conflict could be here to stay are represented by key themes explored in our Global Risk Agenda: geo-economic fragmentation and political instability.

Crucially, we no longer live in a world where the US is the unipolar power, nor even in a world split between two main camps, as was the case in the Cold War. Instead, a multipolar world is emerging, in which middle powers are leveraging their greater wealth and contribution to the global economy to assert themselves on the international arena. In a global context of weakening international institutions and shifting geopolitical alliances, powers great and small will likely feel less compunction in achieving their aims through military means.

Political instability has also been crucial in the rise in conflict. Weak governments and political volatility have created vacuums where militaries, paramilitaries and armed non-state actors have stepped in. In Gabon and across the Sahel, military officers have seized power in nine coups since 2020, while Sudan’s civil war was sparked by the military facing off against the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Disputes to watch

Should geo-economic fragmentation and political instability persist, the upward trend in conflict risk is likely to continue, putting crucial supply chains, on which businesses rely, either directly or indirectly at increased risk.

Our Interstate Tensions Model – which uses machine learning and data science techniques to forecast the risk of two states or self-governing territories engaging in a militarised dispute including the threat, display, or use of force – helps signpost where the next conflict-related disruption to supply chains may come from. Below, we have flagged three bilateral relationships where tense relations may have meaningful implications for key supply chains. While a low probability scenario at the moment, a cross-strait conflict involving China and Taiwan, a major producer of the world’s most advanced semiconductors, would lead to immediate disruptions to the latter’s export of a component that is crucial for modern technology. Wider economic impacts could raise the price tag of a conflict between the two sides to USD10 trillion, an order of magnitude higher than the estimated costs of the Russia-Ukraine war. The risk of a conflict is already driving supply chain diversification as the US, EU and other countries attempt to ‘nearshore’ production of semiconductors to reduce reliance on Taiwan.

Similarly, an outright conflict or even a naval clash between the US and Iran near the Strait of Hormuz, through which nearly 30% of the world’s seaborne oil trade passes, would be a shock to global energy prices. While lower impact, the advance of M-23 rebels in DR Congo’s Kivu province, a group Kinshasa alleges is backed by Rwanda, has also already disrupted the export of tantalum, a key component in electronic products like mobile phones. In all cases, businesses, insurers and investors would face the wider impacts of the increased cost of energy or goods production that these disruptions would entail.

It is not inevitable that this trend of increasing conflict risk will continue, but corporates, insurers and investors cannot afford to be complacent. Prioritising resilience through good risk management practices, such as using horizon scanning techniques, political risk data and predictive models to monitor trends and anticipate potential flashpoints, will not eliminate risk entirely. But the approach can help facilitate strategic planning to mitigate impacts and maximise opportunity, making decision-makers better prepared to respond to disruption events and stay competitive in periods of heightened volatility.