APAC - 5 risks to watch

The Trendline

by Joseph Parkes and Reema Bhattacharya and Dr Kaho Yu and Laura Schwartz and Winifred Michael,

In 2024, Asia hosts elections in some of the world’s largest and most diverse democracies, leaving investors exposed to shifts in the risk landscape. Top among issues to track are drivers of unrest and insecurity, starting with major electoral contests playing out against illiberal trends. The runup to November’s US election will also heighten the region’s complex dynamics of cooperation and conflict in the shadow of superpower rivalry. Meanwhile, emerging Asia’s rising climate change risks and decarbonisation challenges will have to be addressed in the context of worsening debt burdens.

Elections amid illiberal trends boosting unrest

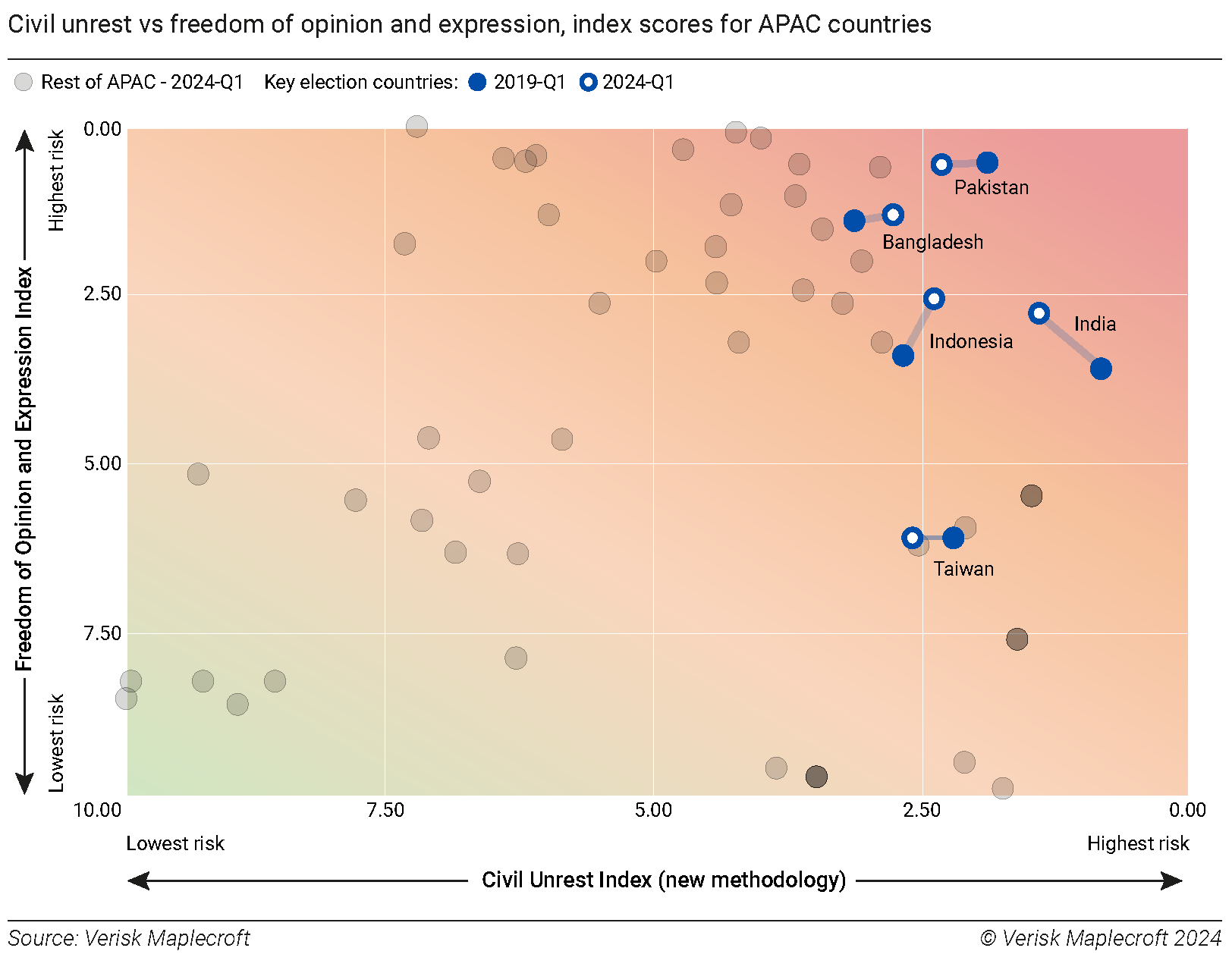

The first half of 2024 brings significant elections in APAC, including Bangladesh and Taiwan that took place in January, Pakistan and Indonesia set for February, and India’s in April/May. Deepening social and cultural divisions, rising inequality, and illiberal democratic trends mean tensions are spiking. Indeed, all the economies listed above feature in the two highest risk categories of our new Civil Unrest Index, which predicts the probability of large-scale protests over the next year.

Elections could add fuel to simmering discontent, particularly with the barriers to expressing dissent rising in India and Indonesia, whose scores on our Freedom of Opinion and Expression Index have deteriorated over the last five years (see chart).

Despite the prospect of raised social and political instability, significant post-election economic policy changes are unlikely in India and Indonesia. Protectionism will likely continue, including import restrictions and export curbs for key commodities. However, leaders across APAC will seek to benefit from Western efforts to diversify supply chains by attracting foreign investment to increase value-added production.

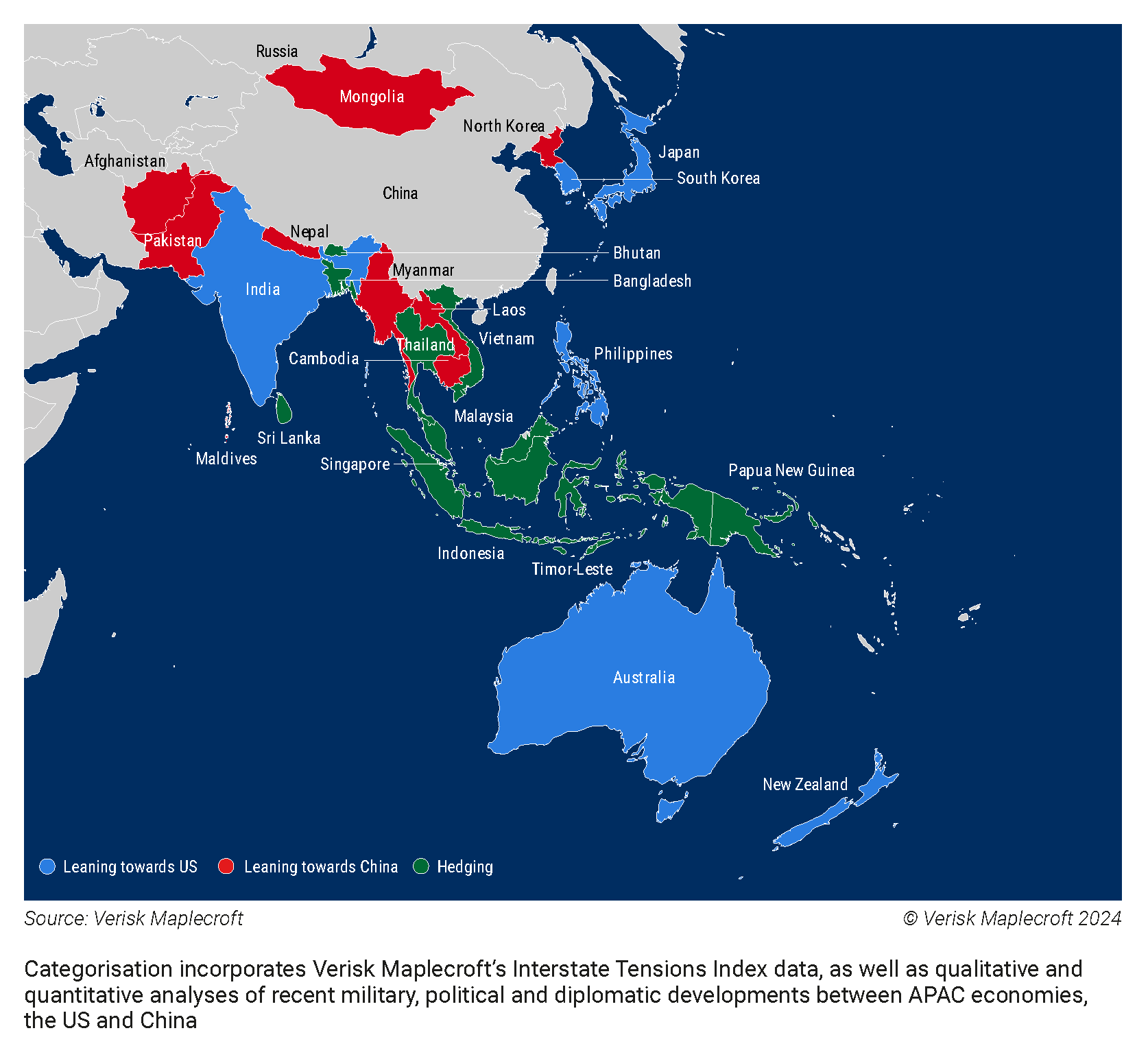

Much of APAC will maintain hedging strategies as US election uncertainty looms

The next US president won’t take office until January 2025, but November’s election will weigh heavily on Asian capitals in 2024. Most countries will continue to avoid picking a side in the superpower rivalry, even if they lean more towards China or the US (see map). But the November vote will offer another indicator of whether the US can maintain its consequential role in APAC.

The long-term trajectory of strategic US-China competition is set in bipartisan stone. That leaves the region’s middle powers, such as Australia and Japan, facing the greatest uncertainty over US policy direction, as domestic politics and conflict in the Middle East and Ukraine increasingly absorb Washington’s attention.

Election uncertainty could extend to regional crises. Geopolitical flashpoints like the South China Sea and the Korean peninsula remain firmly on the radar, but other APAC disputes also have escalatory potential, such as at the Iran-Pakistan border and Myanmar. As expected and unexpected crises arise, question marks over US commitment to the region could further impact stability and create doubt for investors.

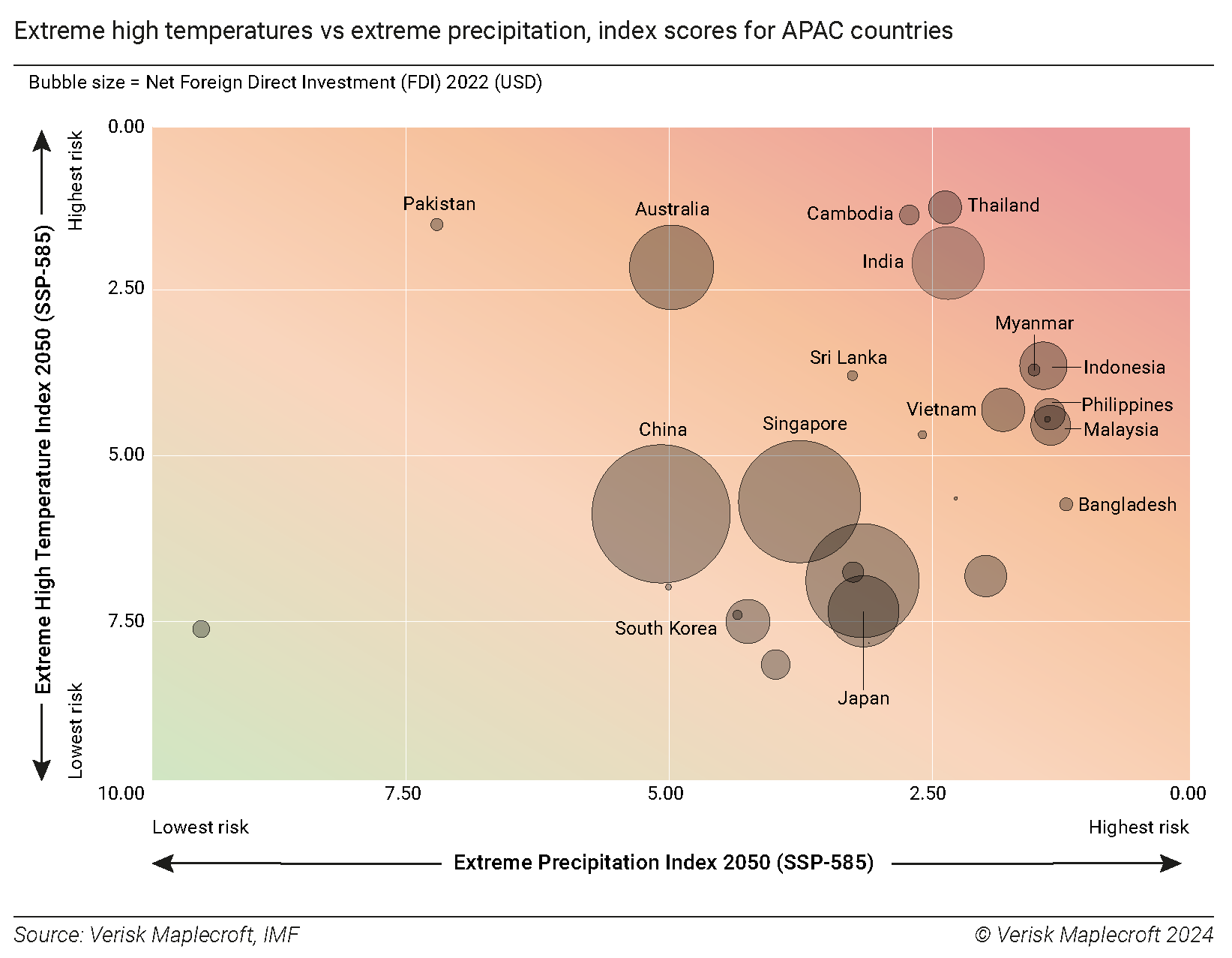

Asia’s growth sectors on the frontline of climate change

As APAC’s real estate and infrastructure sectors boom, extreme weather fuelled by climate-change stands out as a top risk in the year ahead. Global temperatures will likely approach 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels again this year, driven in part by the positive phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. The current El Niño is projected to last until mid-2024, intensifying the South Asian monsoon, and the Pacific typhoon and Australian wildfire seasons. Each risks damage and disruption to existing infrastructure, alongside delays to new projects and spiralling insurance costs.

Our data shows emerging economies in South and Southeast Asia – where demand for new infrastructure is particularly acute – are among the most exposed globally to future climate extremes over the coming decades (see chart). The IMF reports that developing states in the region must invest USD1.1trillion annually in infrastructure to maintain growth momentum and offset climate change. Investors looking to capitalise should pay ever greater attention to climate extremes.

Protracted finance and technology deficits slow the pace of decarbonisation

As green technologies scale up globally, their development and manufacturing will continue to be concentrated in markets such as the US, the EU, China, and Japan. Asia’s developing countries could end up getting the short end of the transition stick. Despite vibrant demand, implementation of green capital will remain fraught with challenges in 2024 due to the lack of a robust, unified green taxonomy framework. Investors will continue to struggle to identify reliable transition projects in key emerging markets that sit in the high to very high risk categories of our Efficacy of the Regulatory System Index.

India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam will remain the hot markets for green investments in 2024. However, competition over land use for energy production, coupled with poor infrastructure planning, will further intensify resource scarcity in these markets, which are already high and medium risk on our Food Security and Water Security indices.

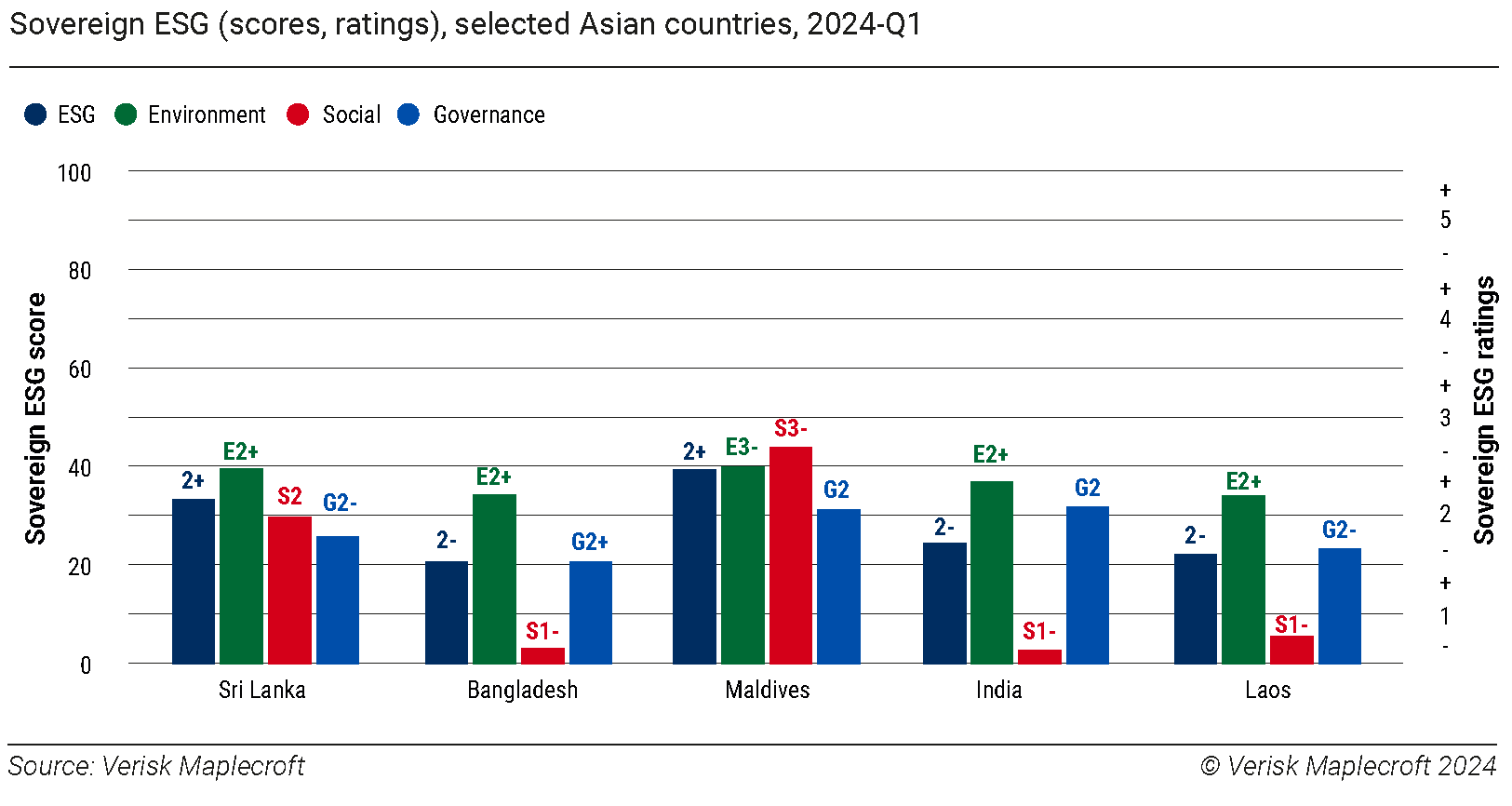

The Sovereign ESG landscape: High debt weighs on environmental and social sustainability

Several Asian emerging markets, including Sri Lanka, the Maldives, India and Laos, show high to very high risk on our Public Debt Index, which will likely depress already weak sovereign ESG performance in 2024.

Sustainable investors should beware of growing trade-offs with highly indebted governments likely to prioritise debt servicing and economic growth over sustainability-related projects. On the environmental side, debt-for-nature swaps may provide governments an opportunity to simultaneously reduce debt and undertake work to protect their natural ecosystems. Laos, Sri Lanka and others have recently pitched, or explored, debt-for-nature swaps.

More broadly, austerity measures to reduce debt will likely impact social safety nets and the quality of health and education, creating fertile ground for unrest, with over half of APAC economies showing high to very high risk scores on our new Civil Unrest Index. Investors may be particularly concerned about the S- and G-pillar implications, especially amid ongoing economic fallout from Sri Lanka’s political and governance crises in 2022.