AI-driven disinformation looms over crunch elections in the Americas

The Trendline

by Robert Munks and Mariano Machado and Jess Middleton,

With numerous countries in the Americas preparing to head to the polls before year-end, we have drawn on our Global Risk Data to better understand how disinformation – classified by the World Economic Forum as the top global risk in 2024 – could pose a threat to governments and business. Our findings show that the major economies of the United States, Mexico and Brazil rank among the five most exposed countries regionally, with Brazil and the US facing upcoming elections.

While disruptive technologies such as AI bring significant benefits, they also constitute an emerging threat that multinational organisations and governments must have on the radar due to their potential to alter the political risk landscape. While we are yet to see its full impacts, AI-driven disinformation could undermine democratic processes and trust in institutions, and fuel political instability and civil unrest, particularly in extremely polarised societies.

Ignoring the signals could also result in companies being unprepared for cascading changes to the operating environment. Shifts in government relations or the regulatory environment might, for instance, take place due to a change of administration where disinformation had an influence on the results of an election. Threats to a company’s activities or reputation may also emerge through the increasing availability of Disinformation-as-a-Service (DaaS) offerings from nefarious actors on the web that could target them directly.

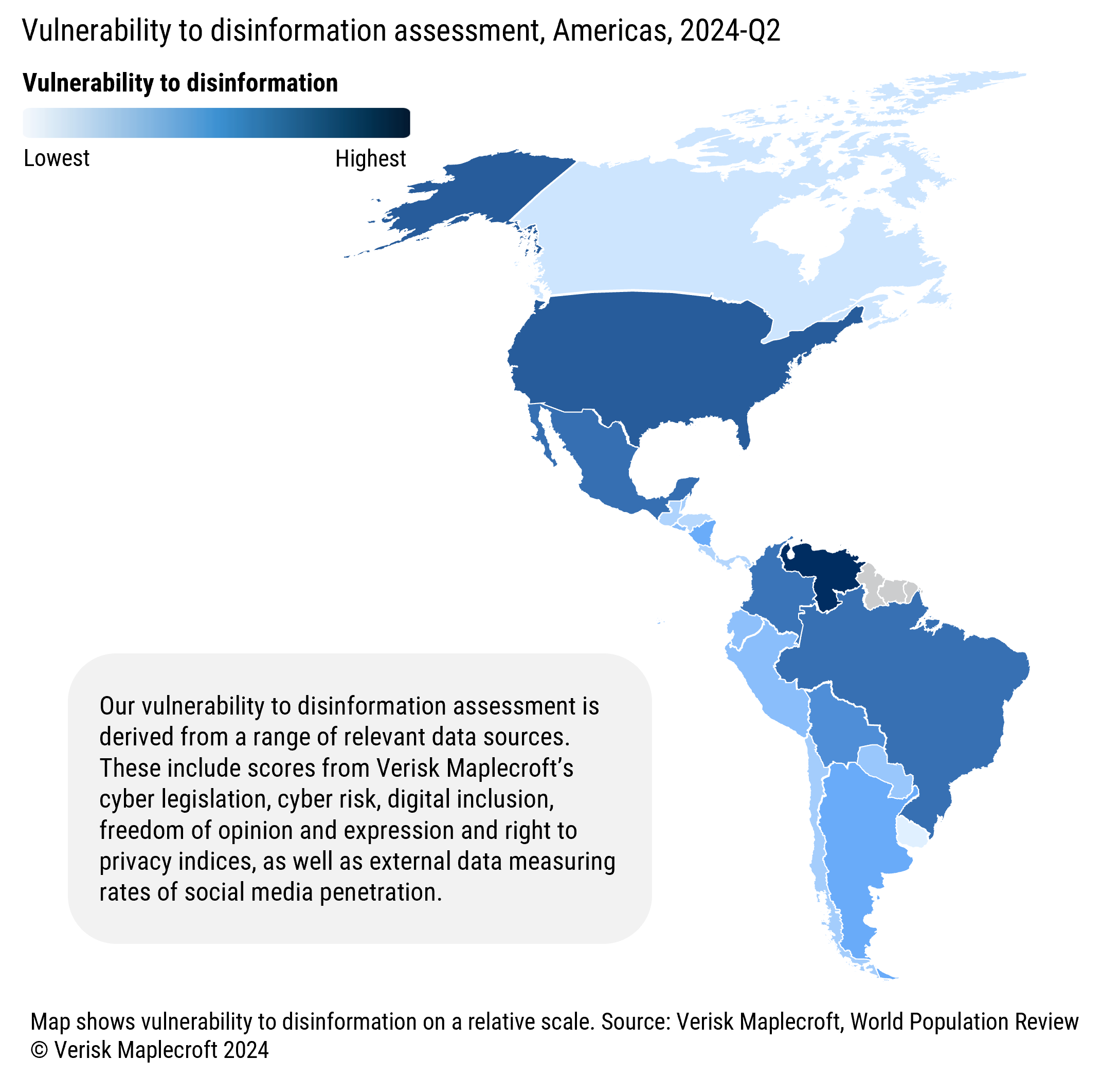

Vulnerability to disinformation varies widely across the Americas region

The potential for disinformation to disrupt elections is compounded by the advent of generative AI, meaning that vectors for disinformation once largely confined to text now encompass images, audio and increasingly video, all with accelerating degrees of credibility.

Many factors play a role in determining a country’s relative vulnerability to AI-driven disinformation, including cyber threats, legislative frameworks, freedom of speech, levels of educational attainment, and the ‘attack surface’ presented by rates of internet connectivity and social media use.

Using a range of proxy indicators for these issues from our suite of 190+ global risk indices, alongside external data evaluating rates of social media penetration, we have developed a high-level vulnerability to disinformation assessment for the Americas to appraise the relative threat levels (see Figure 1).

According to our assessment, Venezuela is the most exposed to disinformation risks in the region. The country has already seen deepfake content used in attempts to shape voter perception, including in 2023, when AI-generated ‘news anchors’ conveyed misleading stories supporting President Nicolás Maduro’s government.

But the distinct feature of the hemisphere is that its three biggest economies, the US, Brazil, and Mexico, rank among the five most-exposed countries in the region for vulnerability to disinformation – and AI-generated content has already begun to play a role in their elections.

The US, which ranks 2nd highest risk in our regional assessment, will be the most closely studied case. Use of disinformation jumped around the 2016 election, although experience to date shows that most election-related disinformation has emerged around issues of fraud and intimidation rather than attempts at undermining candidates themselves. However, we are now seeing this develop and morph in line with advances in generative AI. For example, ahead of the New Hampshire primary in January, a series of robocalls to potential US voters mimicked President Joe Biden’s voice in an attempt to dissuade them from voting.

The US’ performance in our assessment is primarily influenced by its high rates of digital connectivity and social media users that present a significant ‘attack surface’. But it is also undermined by the cyber risk posed by geopolitical competitors, who will see gains in subverting the presidential election by sowing discord and testing their own technological abilities against a primary strategic rival.

Brazil, which ranks 4th highest risk in the Americas, is facing the delicate task of addressing democratic backsliding while also discussing legislation addressing AI-driven disinformation. Prohibitions on AI-generated content in electoral messaging have been issued ahead of the October municipal elections – seeking to create a discouraging environment for content manipulation, while also recognising little state capacity to control a flourishing landscape of rogue actors.

In Mexico (ranked 3rd), outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has already warned about the circulation of fake videos and audio clips featuring his manipulated image and voice with endorsements for investments in state petroleum company Pemex. In early 2024, the ruling Morena's then presidential candidate Claudia Sheinbaum - elected president on 2 June - was depicted in a deepfake video promoting financial services as part of her campaign efforts.

At the opposite end of the spectrum stands Uruguay, with general elections in October, where a robust institutional landscape – including a national AI strategy and discussions around penalising the misuse of AI-generated content for electoral purposes – drives the country’s strong performance on our assessment.

Figure 2: A range of factors is influencing vulnerability to disinformation in key markets

Proliferation of AI complicating efforts to combat disinformation

Against this backdrop, the proliferation of accessible generative AI (the top 50 AI tools attracted more than 24 billion visits between September 2022 and August 2023, according to industry sources) means they could have a significant influence in shaping public opinion through targeted disinformation campaigns.

According to an MIT study, false news travels online faster and more widely than the truth. With deepfakes increasingly easy to create via an ever-expanding range of platforms, the upcoming elections in the Americas will be vulnerable to narratives going viral before they can be debunked.

But the explosion of AI-generated content has left authorities scrambling to introduce regulatory frameworks. The tech industry has recognised the potential for such disinformation to weigh on election outcomes and signed an accord in February to counter the deceptive use of this technology. The UN adopted a draft resolution in March, while nearly 20 US state houses are attempting to pass bipartisan restrictions on the use of AI in campaigns.

The sociopolitical outcomes of disinformation

Quantifying the full extent of disinformation’s harm is complex, with differing levels of impact – from superficial behavioural changes to profound societal repercussions – necessitating nuanced analysis. For the US, Mexico and Brazil, our data shows that disinformation will interplay with already elevated levels of social and political risk (see below) and could exacerbate existing tensions.

Disinformation tactics involving voice-cloning targeting election candidates have the potential to worsen levels of violence against local officials, while sophisticated deepfakes targeting key battleground districts with tailored messaging on sensitive issues, such as immigration, could intensify polarisation and sway voting preferences.

Figure 3: AI applications will interplay with – and exploit – existing faultlines

What impact for corporates and investors?

These risks underscore the importance of staying attuned to emerging issues and signals, which are increasingly influencing political systems across the world. The evolving landscape necessitates a heightened awareness among corporates and investors of the vulnerabilities and risks in the jurisdictions where they operate.

To manage these potential impacts effectively, businesses should implement robust monitoring systems that take in the full spectrum of political risks to detect where disinformation could adversely affect their interests. This will enable them to engage early in proactive risk management strategies and advocate for stronger regulatory frameworks to combat the spread of false information.