Africa - 5 risks to watch

The Trendline

by Aleix Montana and Mucahid Durmaz and Hugo Brennan and Winifred Michael and Eileen Gavin,

Corporates, investors, and insurers with exposure to sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) will face a complex and shifting risk landscape in 2024. Diving into our Global Risk Data, we have identified five key risk trends that will shape the business landscape, including: a slew of elections that will test democratic resilience, deepening insecurity, rising resource governance risks, intensifying geopolitical competition, and the role of international capital markets to meet sustainability goals.

Slew of elections to test democratic resilience

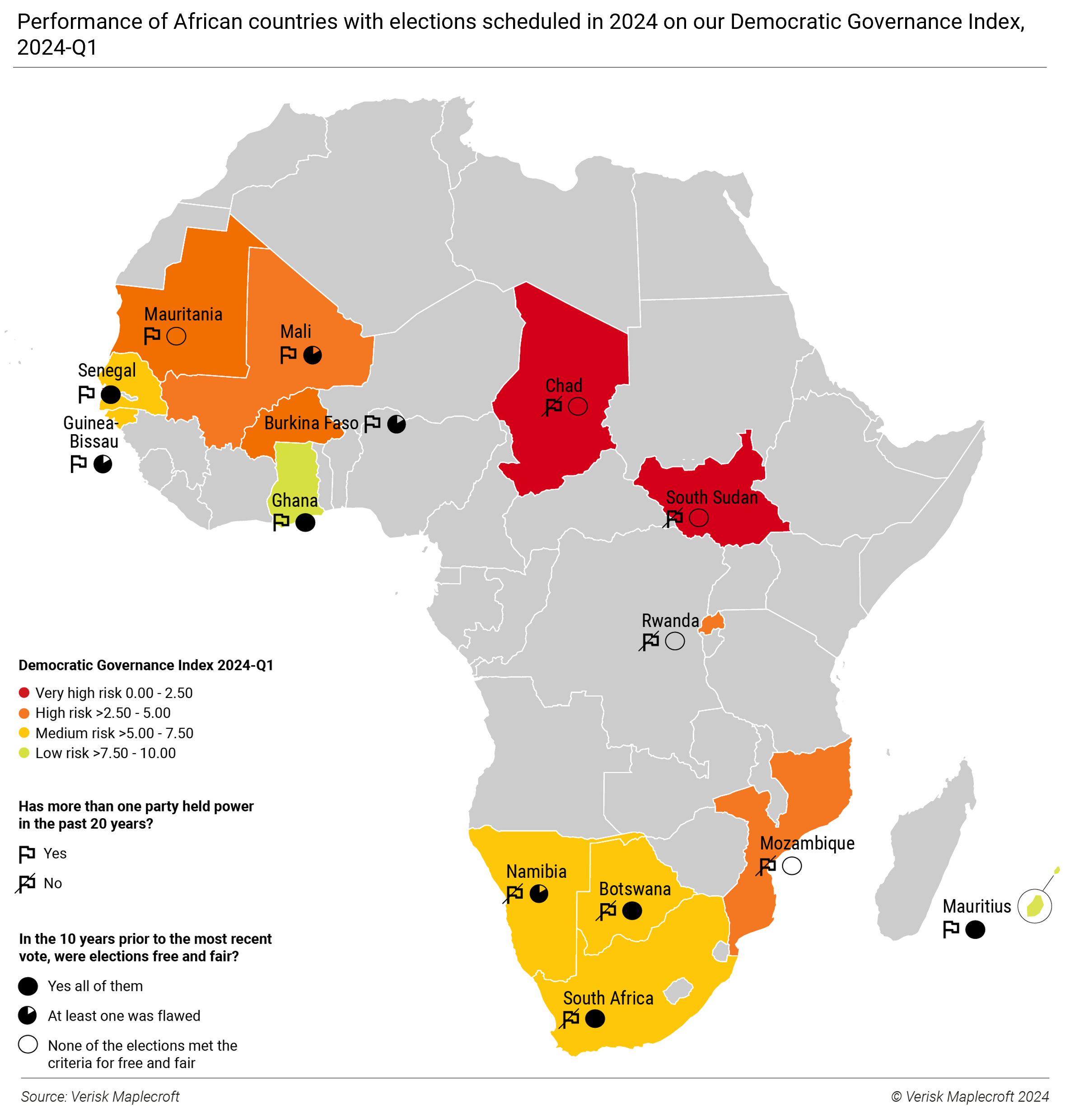

Democracy in SSA will be tested by the 14 presidential and legislative elections set to take place in 2024. This includes South Africa, Ghana, and Senegal, which are among the ten best performing African countries on our Democratic Governance Index. However, Senegal’s democratic credentials have taken a major hit, with President Sall postponing an election slated for February.

In most of the countries heading to the polls, the outcomes of previous elections have been called into question. We expect this democratic backsliding to worsen, especially in the region’s frontier markets. Votes in Chad, Mauritania, and South Sudan, for instance, are set to cement authoritarian rule, if they take place at all. And half of the countries holding elections have had the same ruling party for at least 20 years. With our data showing a strong statistical correlation between our Democratic Governance and Efficacy of the Regulatory Environment indices, investors in these economies could face increasing regulatory risks.

South Africa’s democratic credentials remain strong, but a general election will test the dominance of the ruling ANC. The ANC risks losing its absolute majority in the National Assembly for the first time since 1994, which would force the party to form a coalition. Although drastic policy changes are unlikely, a coalition government would exacerbate political instability.

Deepening insecurity will increase cost of protecting assets and personnel

Security risks are worsening across a swathe of SSA and are unlikely to improve. Since 2021, 19 out of 49 countries in the region recorded a deterioration on our Terrorism Risk Index, while our Counterterrorism Capability Index largely shows no improvement.

Militants in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger will exploit a security vacuum caused by the departure of international forces. Mining companies operating in Sahel countries will be forced to shoulder the higher costs associated with securing their staff and assets. Incursions into northern parts of coastal Western African states will continue. But attacks on major economic hubs, such as Abidjan, Lagos or Dakar are unlikely.

In last three years, Sudan and Ethiopia have recorded a significant deterioration on our Conflict Intensity Index. Sudan’s civil war will continue to rage, while Ethiopia’s fractious political scene risks inflaming violent clashes in Amhara and Oromia that will deter investment despite pro-business reforms. Insecurity in eastern DR Congo remains high, but is unlikely to spread to the southern copper-cobalt belt.

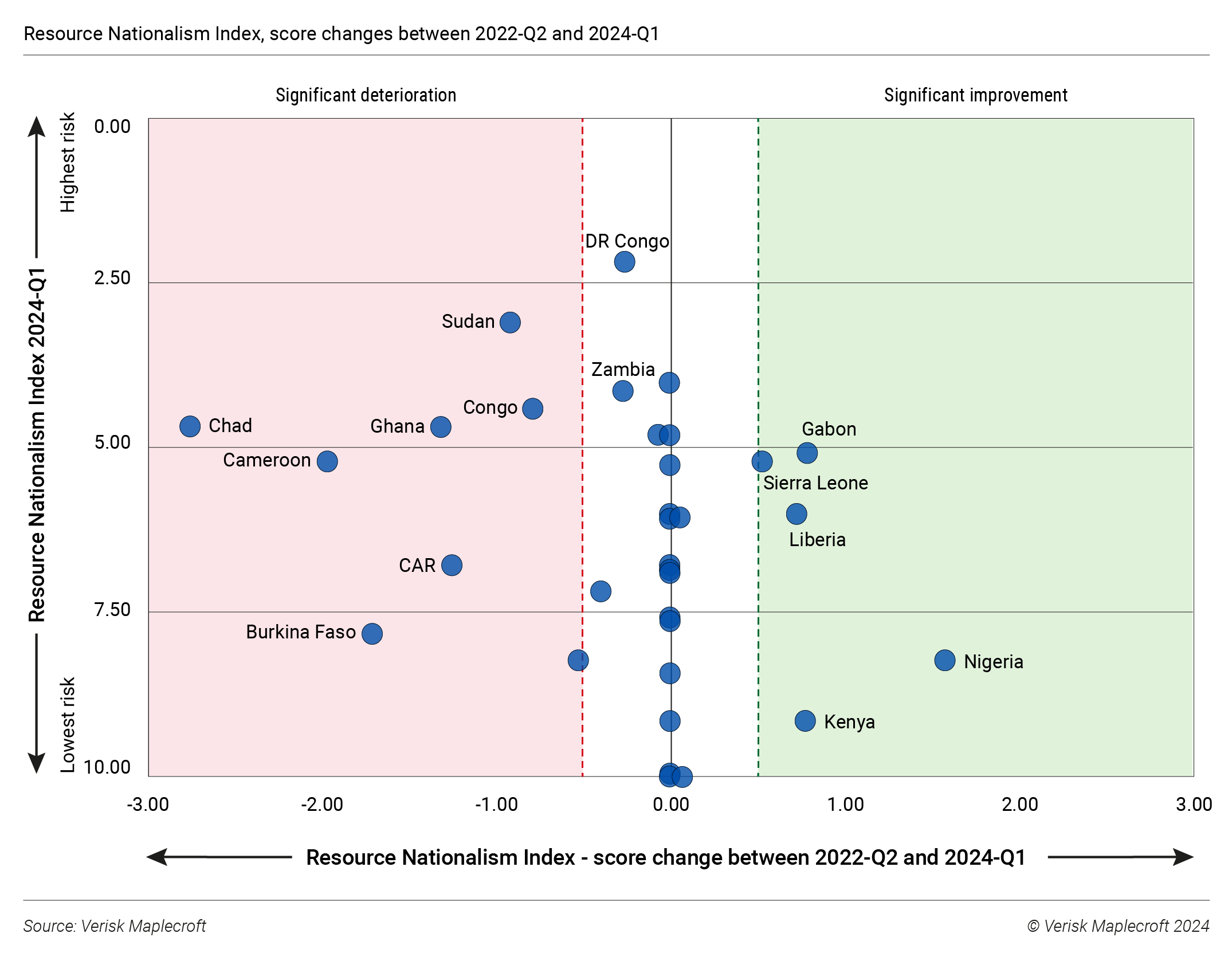

Rising resource governance risks erode foreign investor value

As the global rush for critical materials accelerates, Africa’s resource-rich countries will continue to pursue greater control over their natural resources. SSA witnessed a significant deterioration on our Resource Nationalism Index in 2023, a trend we see extending in 2024.

Last year, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Burundi all revised their mining codes, demanding larger stakes for state-owned enterprises. Similar moves to increase the benefit the state receives are likely in Guinea, DR Congo, Mali, and Zimbabwe, where export restrictions, additional taxes, or more stringent local content and beneficiation requirements may challenge the private sector.

Tanzania could join the growing list of countries banning the export of unprocessed critical minerals in a bid to boost strained public finances. In DR Congo, President Tshisekedi’s re-election means the push to renegotiate existing mining contracts with foreign partners will gather pace. The outlier is Zambia, which will seek to boost FDI into the copper sector via market-friendly reforms.

Intensifying geopolitical competition politicising investment landscape

Geopolitical competition in the region is set to increase in 2024, as the West, China and Russia intensify efforts to extend their economic and political influence. Although most African countries remain neutral, the Ukraine and Gaza conflicts have increased pressure to pick a side.

Investment in the region will become increasingly politicised. Moscow will double down on military support and disinformation campaigns to increase anti-Western sentiment in the Sahel, creating an uneven business environment for Western investors. The West will prioritise strengthening relations with strategic economies, including states that have traditionally had close ties to Russia and are vital hubs in critical minerals supply chains, such as Angola. For example, Washington and Brussels are supporting the development of the Lobito Corridor, a rail link to export metals from the Copperbelt via Angola.

While Beijing is keen to extend its geopolitical influence, Chinese investment patterns are also shifting considerably. After two decades of intense lending to support infrastructure projects, China is downsizing investment in the region due to its domestic economic slowdown and the debt distress risks of African sovereigns. But Beijing will remain supportive of strategic investments in critical mineral projects such as iron ore in Guinea, lithium in Zimbabwe, and copper-cobalt in DR Congo.

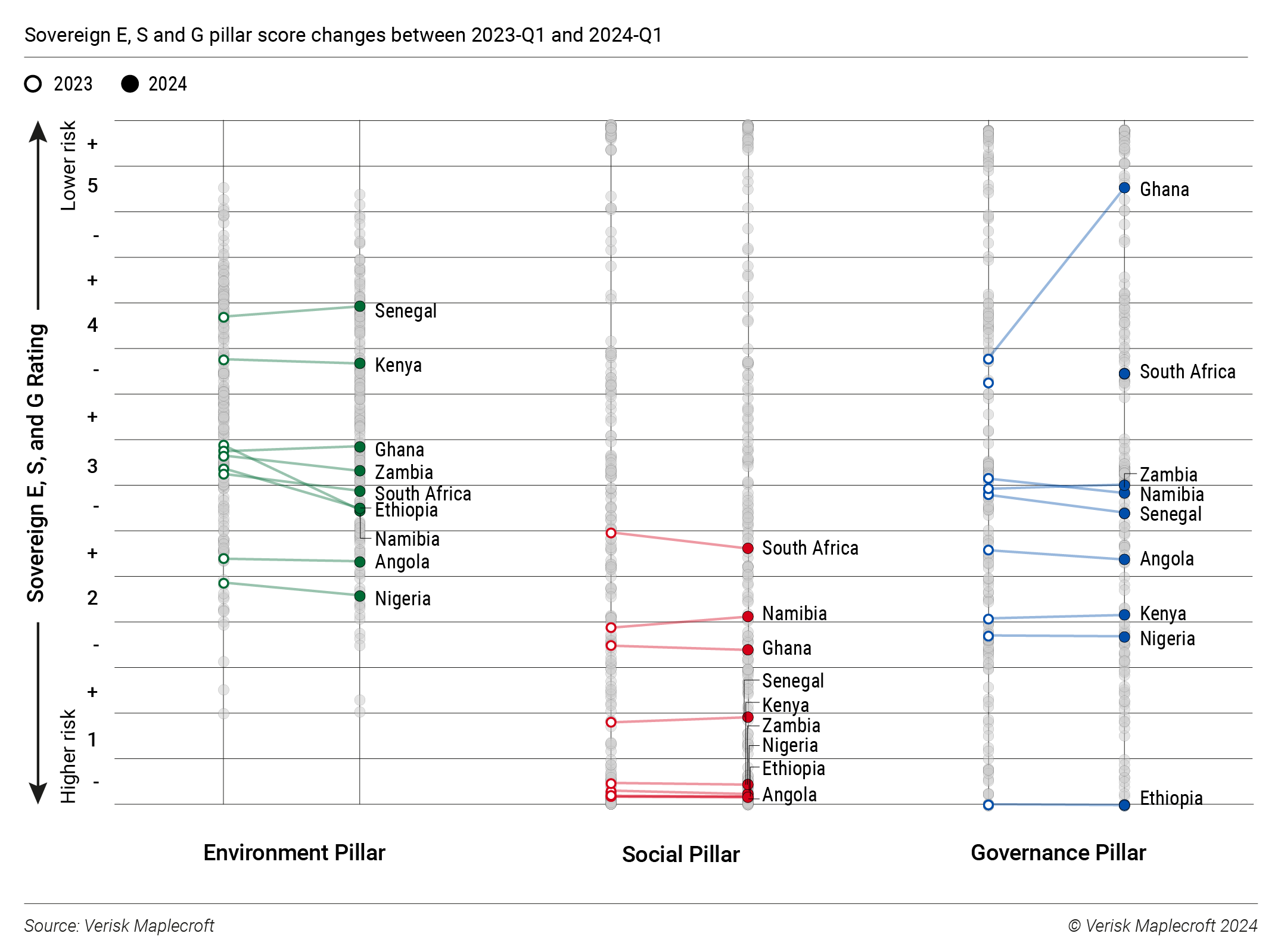

SSA budgets still not stretching to sustainability

Cash-constrained Africa needs to restore international capital market access in 2024, including in support of climate finance needs of USD2.8 trillion to 2030. In January, Cote d’Ivoire became the first SSA sovereign to tap hard currency markets since April 2022. Alongside a USD1.5 billion conventional bond priced at 8.5%, it also sold a USD1.1 billion sustainable bond (SB) at a ‘greenium’ of 7.875%.

Whether other sovereigns can follow suit depends on the progress of debt restructurings and new IMF arrangements. Ethiopia and Ghana are among those hard pressed to accept IMF conditions, including subsidy cuts and currency liberalisation.

Most of the region’s largely junk-rated sovereigns will remain heavily reliant on concessional and donor financing. Notwithstanding pressing social needs, as per our Sovereign ESG Ratings, climate adaptation/mitigation remains the focus.

The IMF’s new Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF) could inject momentum into E and S policies. Kenya is a case in point, with President Ruto mooting sovereign green bonds and debt-for-nature swaps. Having refinanced its USD2.0 billion Eurobond maturing in June, investors would likely be receptive to a labelled bond moving forward.