UK’s post-Brexit Pacific trade deal fraught with environmental and human rights risks

by Jess Middleton and Reema Bhattacharya,

In April, the UK announced it had struck an agreement to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a trading bloc of 11 nations including Japan, Canada and Australia. Westminster has hailed the move as a major post-Brexit win and a signal of Britain’s strategic ‘tilt’ towards the Indo-Pacific.

But multiple conservation groups have argued that the UK’s entry into the bloc could encourage deforestation overseas, particularly in Southeast Asia. Their concerns centre on the fact that prior to joining the pact, London agreed to eliminate a 12% tariff on Malaysian palm oil - a product used in everything from biofuels and biscuits to soap and cosmetics, but widely associated with the destruction of primary rainforests.

Figure 1: Deal to join CPTPP marks UK tilt towards the Indo-Pacific

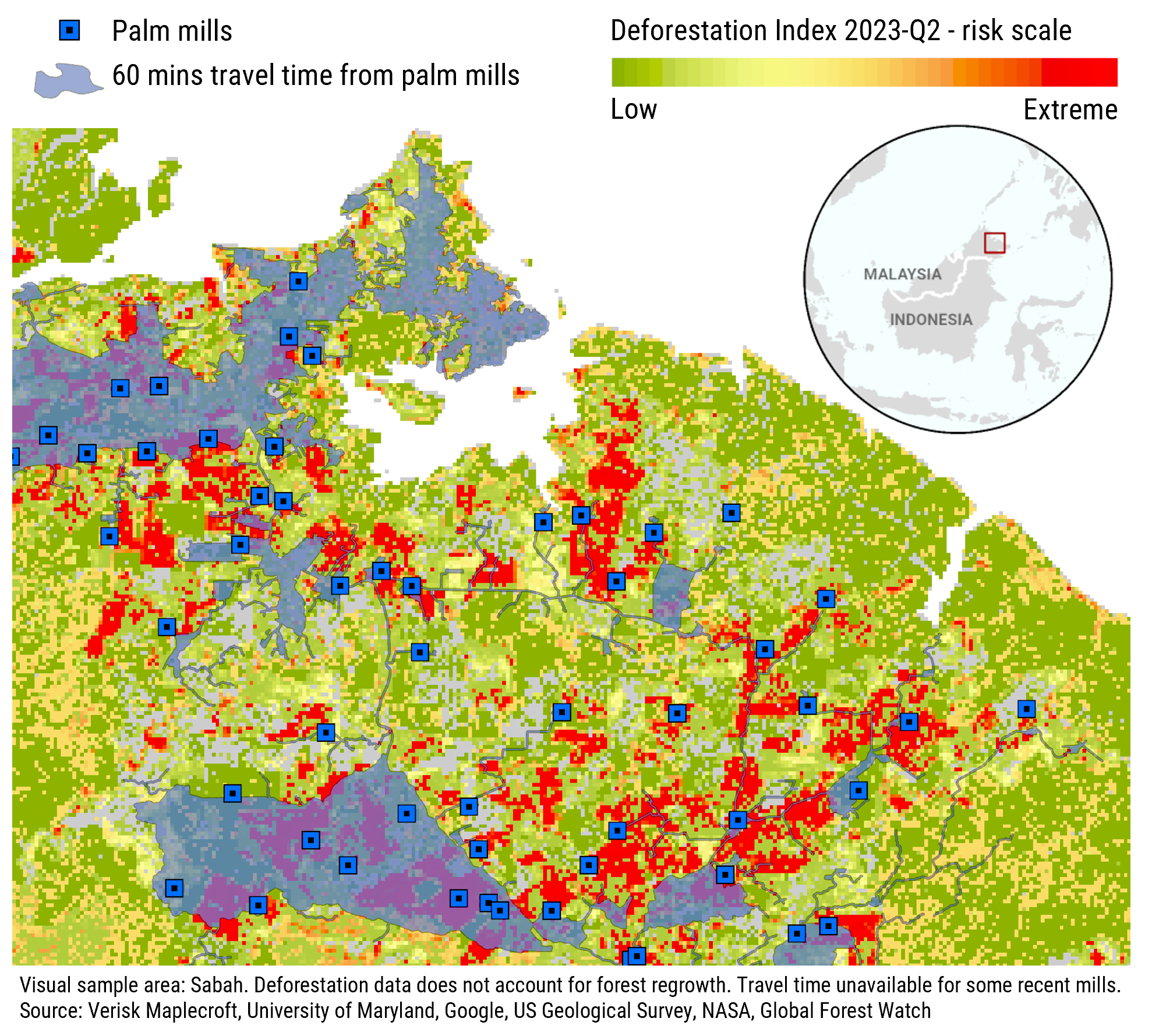

Data from our Deforestation Index highlights the extent of the issue. Malaysia is the 15th highest risk country globally on the index. It is also rated extreme risk for deforestation tied directly to palm oil production, according to data from our Commodity Risk dataset. Drilling down further, our geospatial analysis shows that Malaysia lost just under a quarter (23.8%) of its forest cover between 2000 and 2021. This figure jumps to 31% when looking at areas within an hour’s drive of a palm oil mill.

The new stance adopted by the UK is welcome news for Malaysian authorities, who have been scrambling to maintain the competitiveness of their exports in response to Western anti-deforestation laws.

These include the EU Renewable Energy Directive, which was revised in 2018 to include a planned phase out of palm oil-based fuels by 2030, amid overwhelming evidence of the product’s negative environmental and social impacts. The move drew a fierce response from both Malaysia and Indonesia, who accused the EU of protectionism and threatened trade retaliation.

Across the Atlantic, the US has in recent years banned imports from several major Malaysian palm oil producers over human rights concerns. Indeed, Malaysian palm oil production receives an extreme risk rating for a host of social issues in our Commodity Risk dataset, including child labour, forced labour and human trafficking.

For the UK meanwhile, bending to Kuala Lumpur’s demands on the issue have added to concerns that London is taking a step back from its international commitments to human rights and the environment.

In April, the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS) called on ministers to do more to enforce supply chain transparency rules, after a study revealed the only 29% of the UK-based organisations required to produce a modern slavery statement did so in 2022. At the same time, the number of British officials dedicated to the climate crisis has dropped sharply since 2016, with Westminster axing its top climate diplomat post last month.

The removal of tariffs on Malaysian palm oil is yet another signal that the UK’s approach to ESG issues has softened in comparison to the EU’s post-Brexit.

“Going forward, the UK will need to reassure ESG-conscious investors that it will maintain its regulatory rigidity and avoid granting further concessions if it is going to maintain its reputation for high environmental and social standards,” says Europe and Central Asia Research Associate Fabrizio Farina.

“In the meantime, UK-based businesses will need to work harder to ensure that their products do not become tainted by commodities that are increasingly out of step with ESG requirements in the rest of Europe.”