TNFD launch marks giant LEAP for businesses

by Will Nichols and Rory Clisby,

While all economic activity is dependent on nature, commerce’s impacts and dependencies on natural capital is largely unacknowledged. But that’s set to change with the advent of the Task Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), whose final benchmark, released earlier this month, aims to create a standardised way of measuring threats to wildlife and ecosystems, as well as where they deliver value.

The standard intends to follow the playbook of its older cousin, the already well-established recommendations of the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFDs), by unleashing a wave of calls from the investment community for corporates to account for impacts and dependencies on nature, especially across assets such as mines, oil operations and pipelines.

A worldwide biodiversity deal secured in Montreal last year alongside developments like a new Law of the High Seas and a recognition of how human rights are affected by environmental degradation is set to drive momentum for the introduction of hard regulations addressing biodiversity risk.

In the same way as carbon restrictions threaten emissions-heavy investments, so more stringent biodiversity laws will affect activities impacting nature. One estimate suggests the world’s largest investment banks provided around USD2.6 trillion (GBP1.9 trillion) of loans and underwriting services linked to the 'destruction of nature' in 2019. With huge sums under threat and pressure from legislators and civil society growing, investors – and operators – need to find a way to manage this risk.

TNFDs among key steps to cultivate a global framework

Biodiversity risk is a factor of both the presence of valued ecosystems and species, as well as a country's intent and capacity to protect them. But measuring these risks requires universal benchmarks.

The final TNFD recommendations, released at New York City Climate Week on 18 September following two-years of consultation, will be a key component in standardising measurement of biodiversity impacts and dependencies. At the same time, TNFD is encouraging companies to embed natural capital factors into decision-making and strategies. So, as well as examining their impact on nature, organisations will also be encouraged to map out the extent to which their business models require natural capital inputs, such as pollination, clean air, or fresh water.

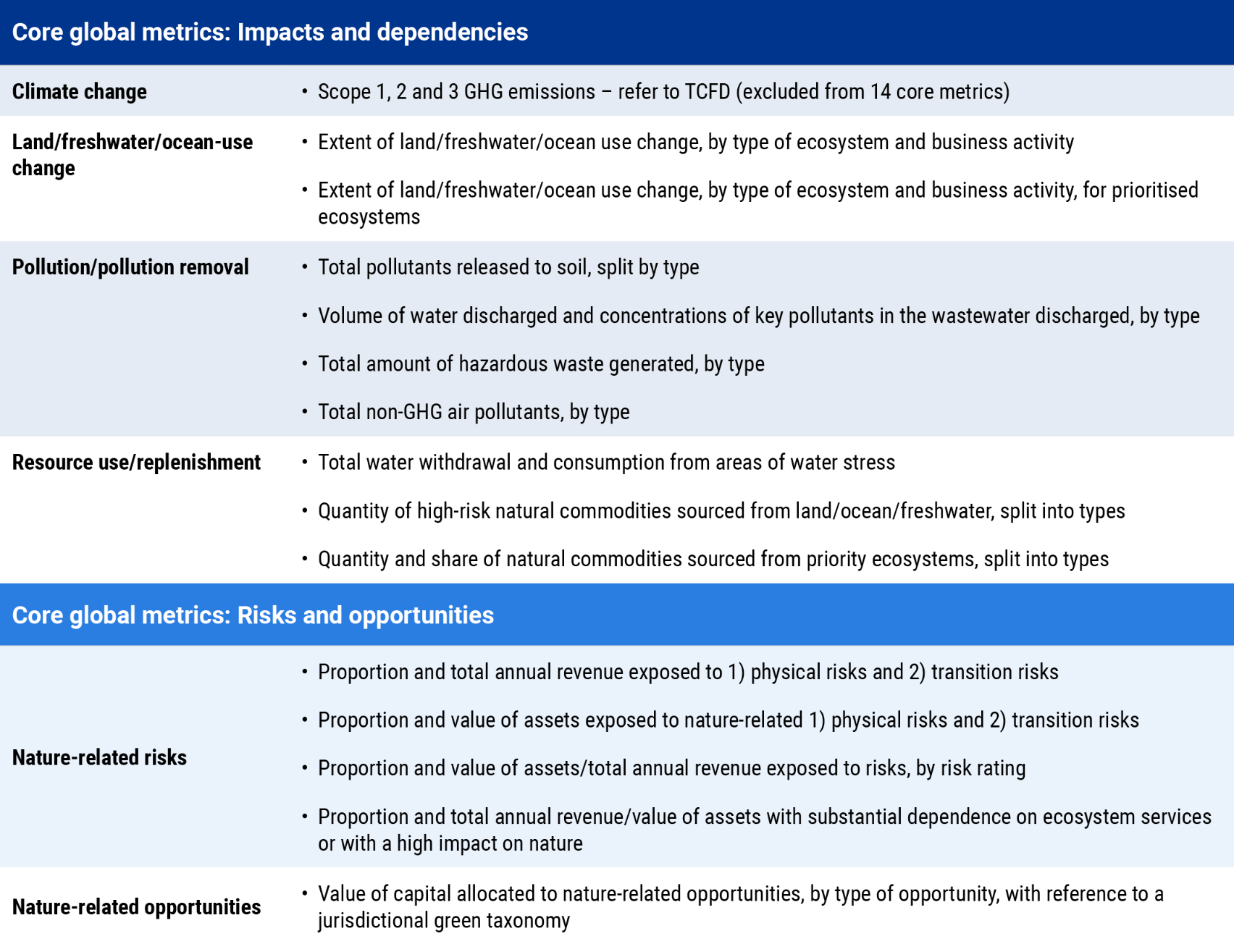

The TNFD benchmark provides a simplified, systematic process to account for impacts and dependencies, as well as core metrics to support the alignment of cross-sector and sector-based reporting.

In its additional guidance for the financial sector, the TNFD sets out two core disclosure metrics – exposure to sector and exposure to sensitive locations – along with additional metrics mapping to the principal adverse impacts (PAIs) under the EU's Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR).

The guidance emphasises that financial institution targets "should be oriented toward driving changes in the real economy".

Data will be central to addressing natural capital impacts and dependencies

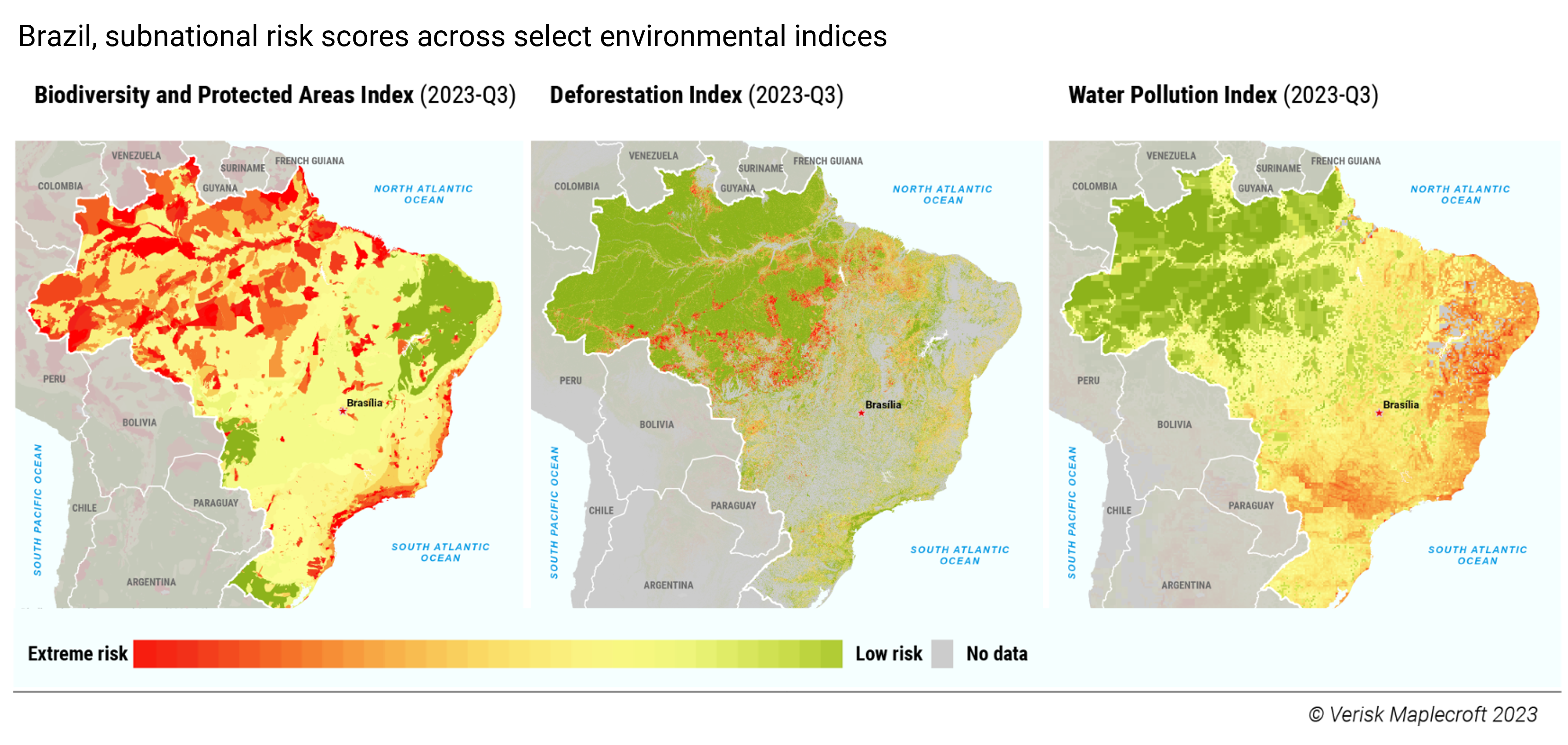

Clearly, high-quality data will be important not only for reporting, but also to understand the context in which an organisation operates – its proximity to important ecosystems throughout the value chain, whether corruption is providing cover for destruction of nature, and how stringently a government is managing its natural capital.

Yet, one of the key challenges of the TNFDs is that metrics for assessing and quantifying nature loss and material dependencies are less well defined than the climate metrics demanded by the TCFDs. Initial steps of the LEAP approach (Locate, Evaluate, Assess, Prepare) advocated by the TNFD can be met by using available data sources to screen asset and operational exposure to threats around biodiversity, water pollution, deforestation, and other key metrics before delving deeper into both sensitive and materially important locations.

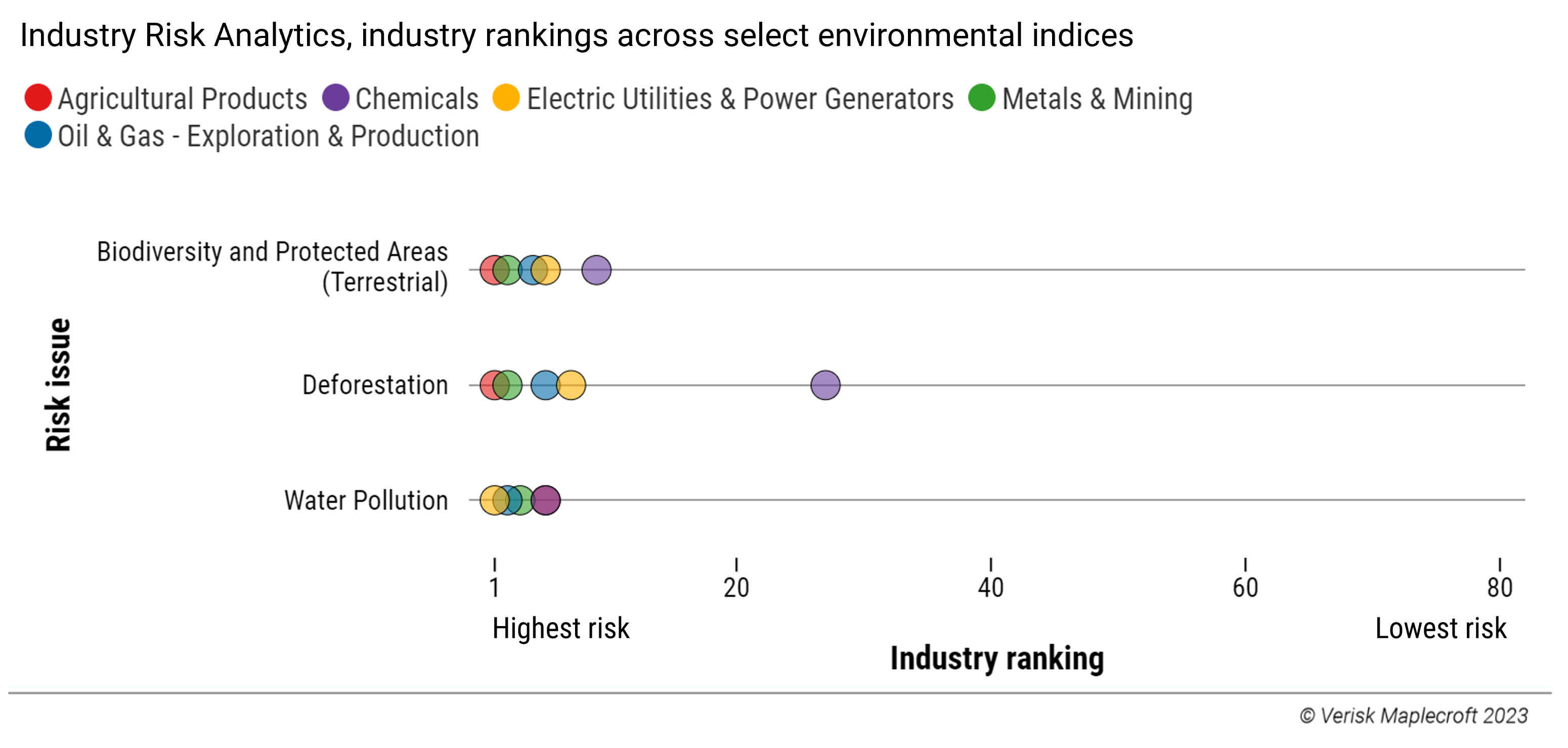

However, identifying dependencies will require company, biome and industry-specific data. Business and investors will also likely find the best approach is to combine internal and external data sources. Our Industry Risk Analytics dataset indicates that agricultural production and upstream and downstream extractive operations will have the highest biodiversity, water pollution, and deforestation risk profiles.

Similarly, scenario analysis under the TNFDs will also be harder to define than for climate risk and parameters to defining those scenarios are yet to be fully finalised. More qualitative scenarios will be required, onto which quantitative data can be layered. These will likely be based on two critical uncertainties: the level of ecosystem degradation and the alignment of market and policy.

For sovereign investors, ongoing debt issues in emerging markets offer potential opportunities for engagement or debt-to-nature swaps as seen in countries such as Belize, Gabon, Ecuador and Barbados – although these have proved controversial.

Those countries furthest away from the 2030 Montreal-Kunming targets of protecting at least 30% of terrestrial areas and 30% of their seas could be notable targets for ESG investors, while operators in those nations must be aware of the potential for safeguarded areas to expand.

Biodiversity risk blossoms

Given the complexity of the requirements of the TNFDs, stakeholders will undoubtedly be given breathing space as the new framework beds in: the TNFD does not expect disclosures to start aligning with its recommendations until at least 2026. Even so, the financial sector, alongside real asset operators dependent on its capital, need to put resources towards tracking, measuring and managing biodiversity risk. The lesson from climate risk reporting is that certain existing processes can be repeated, but a new way of thinking needs to be embedded from the top down to truly realise the benefits.

And the benefits of getting the process right are substantial: identifying and mitigating biodiversity impacts helps investors and corporates anticipate regulatory shifts and shield themselves from reputational and litigation risks. And, just as with climate risks, there is an opportunity to make smarter investments that tap into the potential of preserving and enhancing ecosystems and natural capital services.