Climate and environment - 5 risks to watch

The Trendline

by Rory Clisby and Will Nichols and Liz Hypes,

Last year was the hottest ever, but, with a host of recent studies suggesting worldwide average temperatures will consistently exceed the Paris Agreement stretch goal of limiting global heating to 1.5°C, records will continue to tumble. Although media coverage of climate dipped 4% over 2023, this year governments, businesses and investors will need to keep climate threats top of mind. Here are five areas we see coming to the fore.

2024 to be a wait-and-watch year before COP30

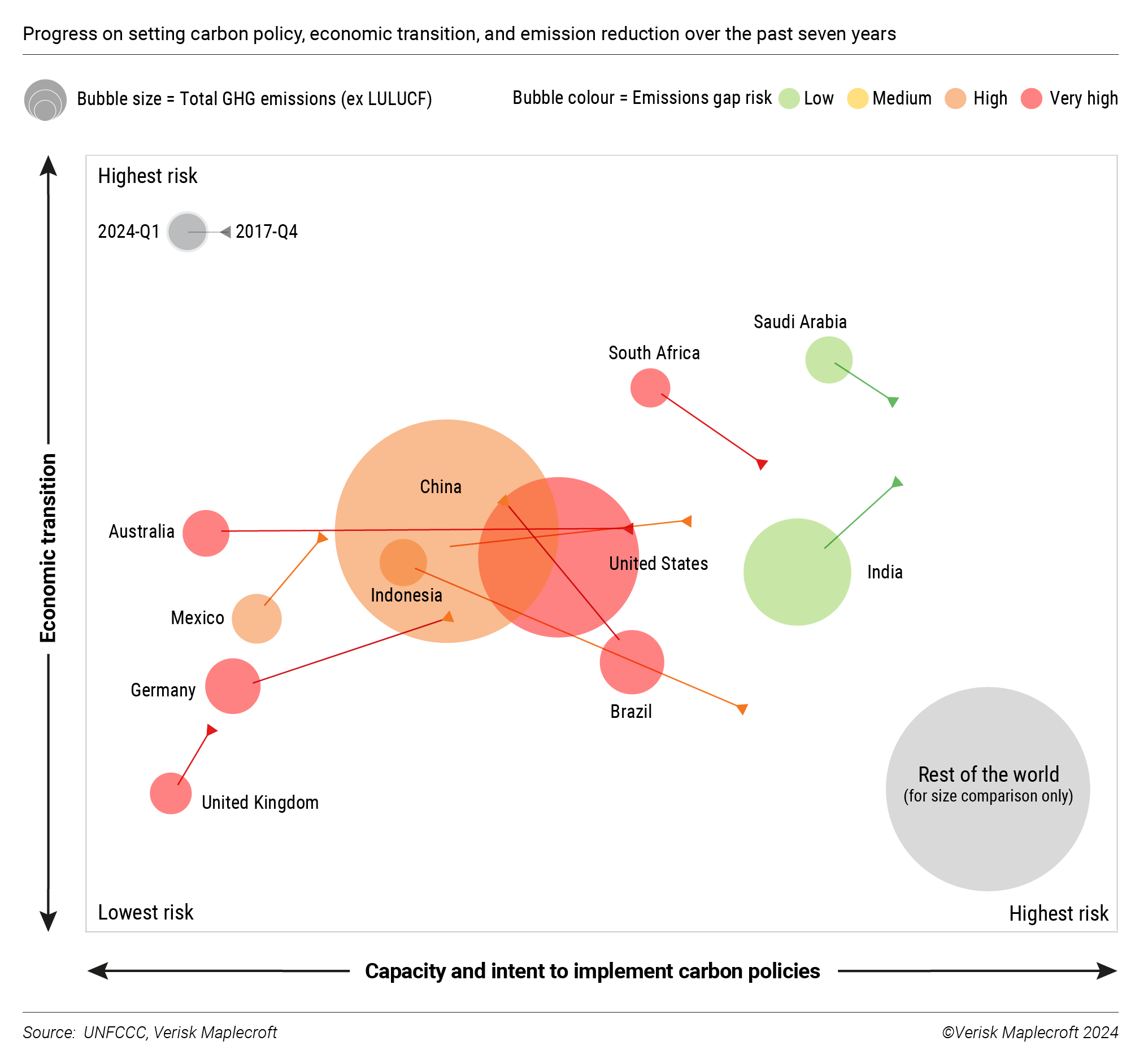

The reality is that current climate policies will see temperatures rise 2.5°C-2.9°C by 2100. The limited, albeit united, call to transition away from fossil fuels that emerged at COP28 in Dubai will not improve this trajectory. Major emitting countries need to accelerate progress on climate regulations, which would see right to left movement on the x-axis in the graph below.

As the chart shows, since 2017, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Indonesia have become more carbon intensive, while the US has been at a standstill. Significant emissions gaps among key countries suggest that curbing fossil fuels will prove difficult.

Yes, global clean energy investment grew 17% to USD1.8 trillion in 2023, but that is about a third of what is needed to 2030 to meet the Paris goals. Key provisions of the US Inflation Reduction Act, expected in 2024, will not meaningfully close the gap, while the UK is actively rowing back on climate initiatives.

Very little suggests we will see the requisite action ahead of a low visibility COP29, with countries likely to leave updating climate plans to the late 2025 deadline. Once again, corporations will need to be the catalyst for climate action.

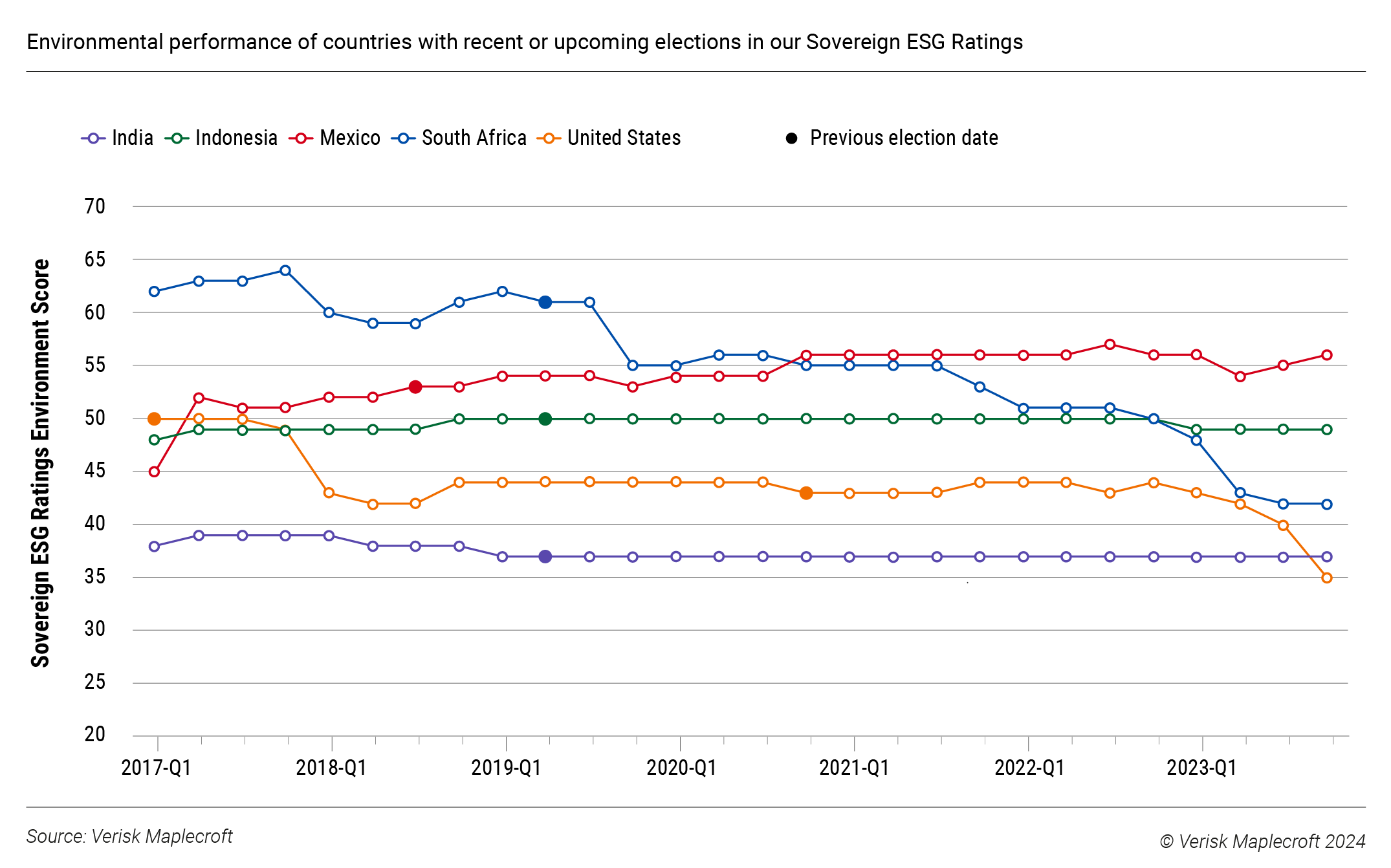

Climate on the ballot as global democracies go to the polls

Over half of the world’s population will head to the polling booth in 2024, with profound impacts for the direction of environmental policies outlined above. After 2022 saw Australia’s green-leaning Teals upend the election landscape and Lula oust Bolsonaro in Brazil, last year climate change sceptics were elected in Argentina and the Netherlands – and more could follow. Four of the world’s six largest emitters go to the polls in 2024 – the US, EU, India and Indonesia – and the outcomes will be significant for the climate.

As shown below, none of these three nations have seen their environmental scores in our Sovereign ESG Ratings improve since the previous election. Indeed, most major emitters see a similar pattern.

Indonesia’s presumptive new President has a chequered environmental record, while in India, the BJP Party – favourites to win a third term – has overseen a loosening of environmental regulations and rapidly rising emissions.

But Donald Trump regaining the White House would likely preface a blow to global climate efforts. Yes, renewables continue to make rapid progress in ‘Red’ states, largely due to their economics, but, based on his historical actions and public statements, a second Trump term would likely see withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, limited collaboration with China on climate objectives, and a reeling back of environmental regulation.

How green is green hydrogen?

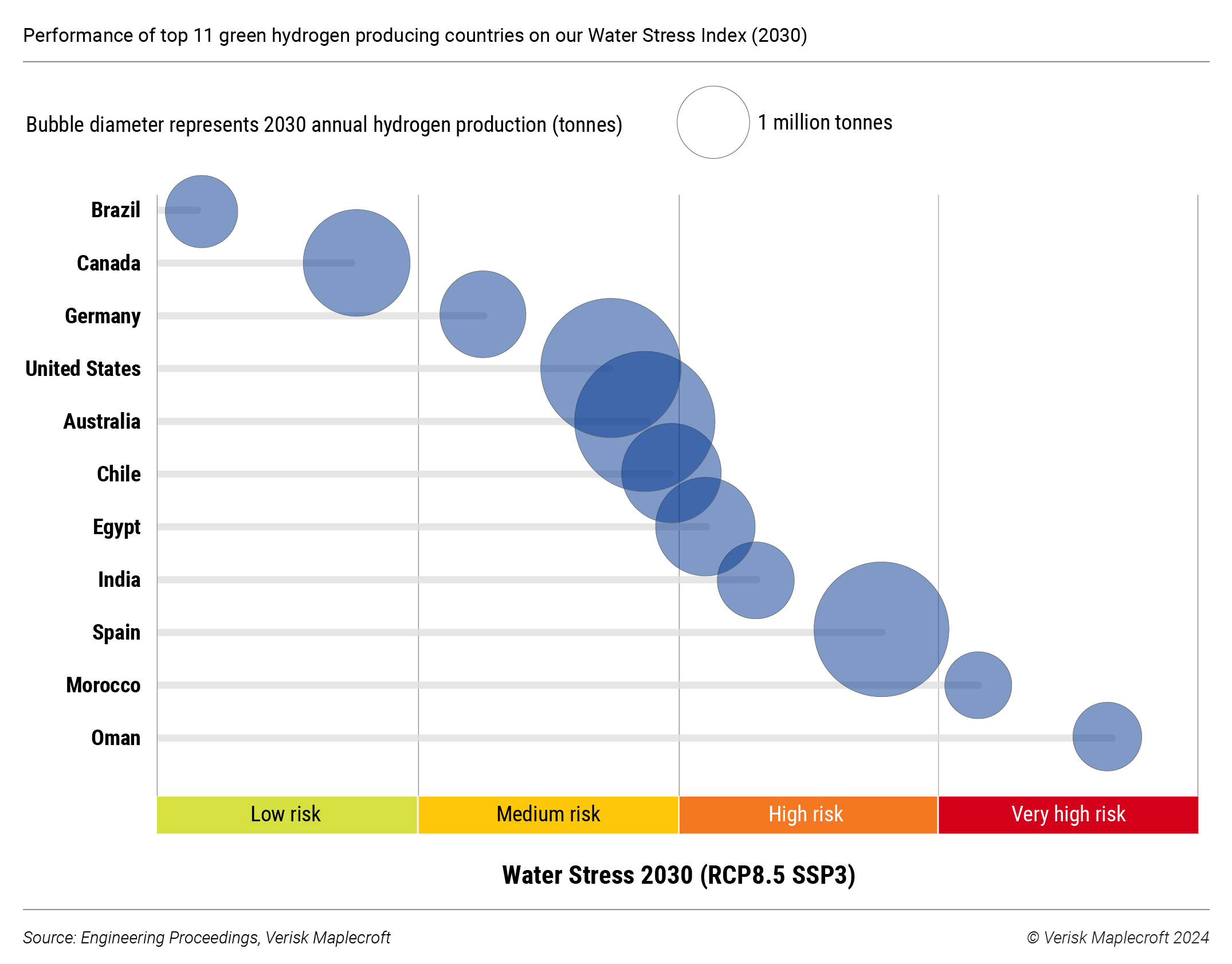

Hydrogen produced via renewable energy is being touted as a means of decarbonising heavy industry and transport. And governments and energy companies across the world are going big on 'green hydrogen'. Announced investments increased by 30% across the first nine months of 2023 and that momentum is expected to continue this year. The EU has launched auctions worth EUR3 billion, while aiming to produce 20 million tonnes a year by 2030, with major government-backed projects also set come online in the US, Australia, China, and India.

Yet, hydrogen production is highly water intensive – nine litres of water are required to produce a single kilogram of hydrogen. And many countries positioning themselves as major suppliers of EU green hydrogen also suffer from high levels of water stress.

Of the projected top 11 global green hydrogen producing countries by 2030, five are rated high or very high risk in our Future Water Stress Index and another three are vulnerable to becoming high risk (see chart). These include Oman, Egypt and Morocco, all of which are positioning themselves as major suppliers of EU green hydrogen. As production ramps up, communities facing water shortages could well start to oppose projects, raising the question among investors and policymakers: is green hydrogen truly green?

Supply chain disruption set to rise

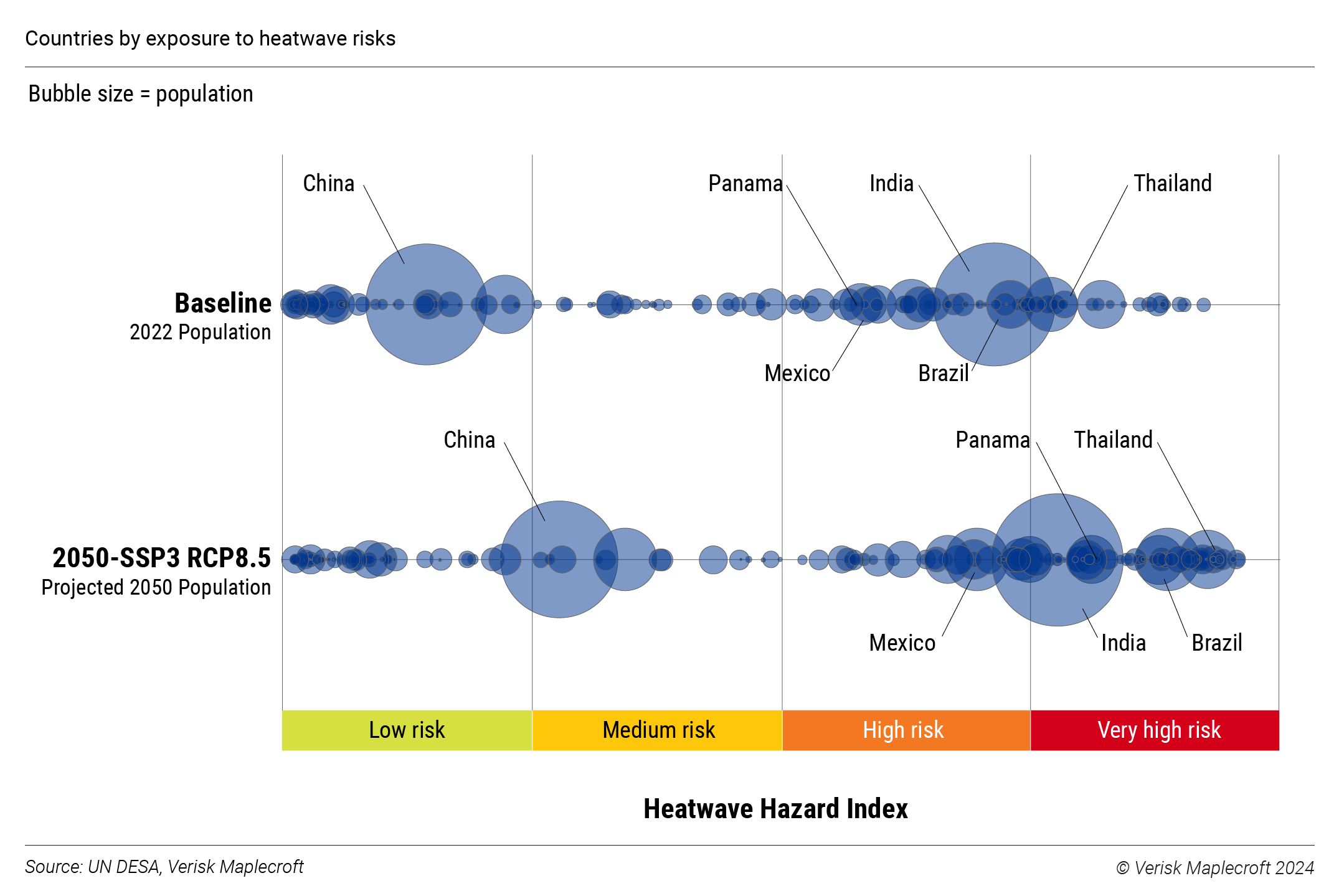

In the worst-case scenario, 2024 could herald the start of accelerating climate shifts as the Earth crosses environmental tipping points.

The fallout isn’t limited to climate-threatened nations: El Niño-fuelled drought is causing water shortages in the Panama Canal that is delaying shipping and pushing up prices of goods, especially for large importers like the UK and EU. Weather-related declines in rice, wheat and palm oil production in Asia, and delays to South American soybean harvest are also hitting national budgets and market prices internationally.

Worsening climate-related events should spur corporate momentum towards building more resilient supply chains. By 2050, an extra 2 billion people will be living in areas at very high risk of extreme precipitation and 3.2 billion more in areas at very high risk of heatwaves, including in key commodity and goods exporters such as Brazil, India and Indonesia.

Reporting gets serious

2023 marked a significant shift in the ESG reporting landscape with the approval of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and release of IFRS standards S1 and S2. Implementation of CSRD and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) in 2024 means large companies both within and outside the EU must start gathering data about their climate and environmental performance. Essentially, non-financial data is being treated in the same way as financial data – and in many cases organisations’ internal structures are not set up to manage this effectively.

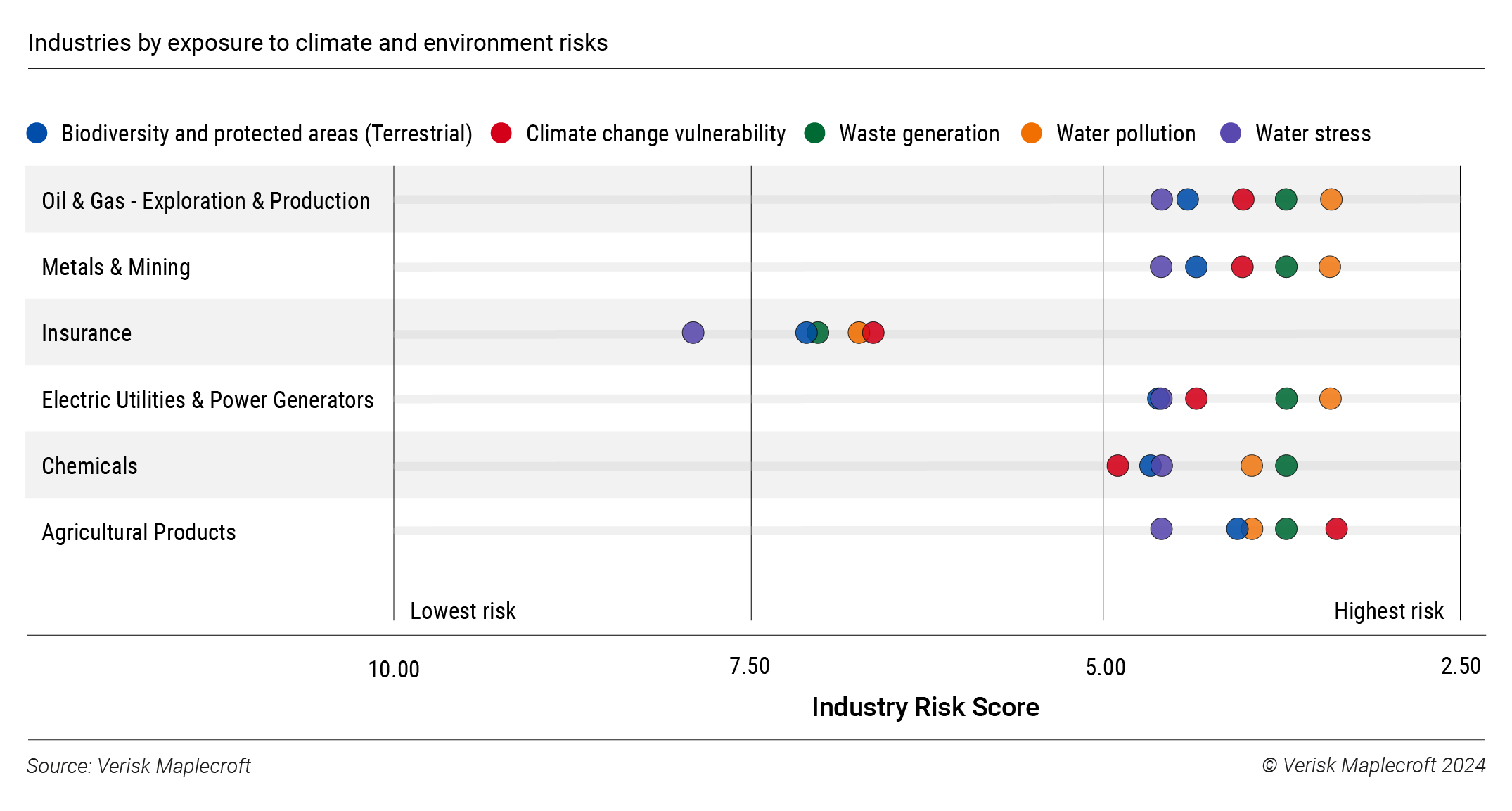

ESRS includes five environmental standards that focus on climate change (standard E1), pollution (E2), water resources (E3), biodiversity (E4), and waste (E5). Below, our Industry Risk Analytics dataset shows that these topics will likely be material for many industries, including energy, chemicals, oil and gas, and mining, putting them at the forefront of disclosures.

The expected adoption of IFRS S1 and S2 standards by many countries and jurisdictions including the UK, Canada, Brazil, Singapore and Japan – alongside the delayed SEC rules on disclosures – means there will be no escape from mandatory ESG reporting for some of the world's largest corporates. Significant penalties for erroneous disclosures or perceived greenwashing mean there is little choice but to take this seriously.