Cascading climate risks are a threat Latin America must take seriously

by Will Nichols,

Record temperatures, wildfires, storms and floods have all made headlines in 2023 as the world braces for a new climate reality. But the secondary impacts of these climate shocks cannot be ignored.

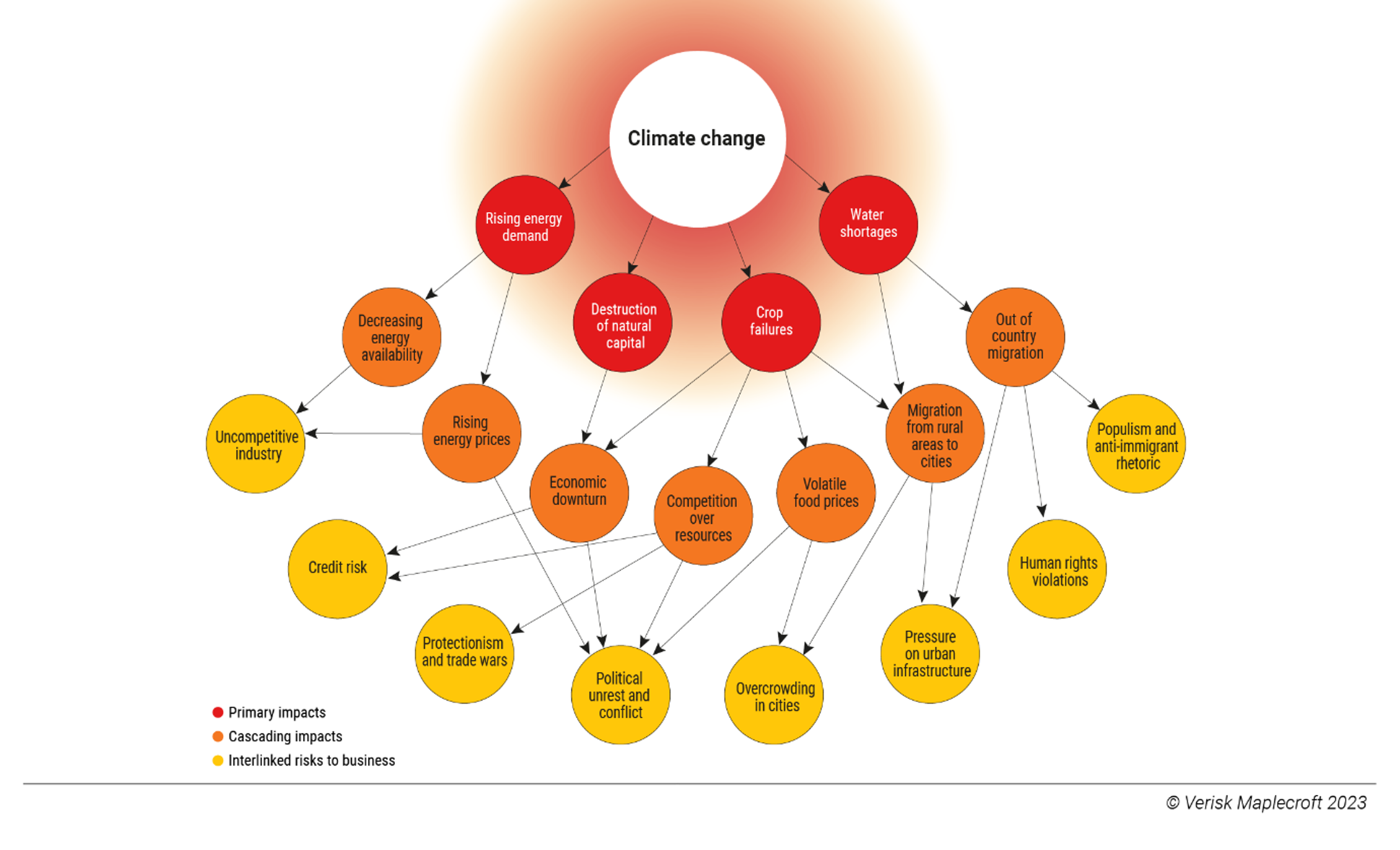

Governments and business organisations in Latin America must ask difficult questions about the relationships between climate impacts and secondary risks, including:

- How does a ruined harvest impact national finances and food security?

- What additional pressures on urban housing and infrastructure occur as people move into the cities from collapsing agrarian communities?

- To what extent will mass migration trigger populist politics, spark civil unrest or act as the catalyst for conflict?

Yes, many private sector stakeholders are beginning to create extensive mitigation plans for physical climate threats. But failing to recognise the sweeping impacts that ‘cascading climate risks’ will have on populations, economies, and commercial entities the world over would represent a major lapse in business and national strategies.

Conceptualising cascading climate risks

Identifying where cascading climate impacts will manifest, and how resilient countries are to these risks, is the first stage of addressing and managing these threats. At Verisk Maplecroft, we used our portfolio of risk indices and a statistical method called “cluster analysis” to create the Cascading Climate Risk Resilience Model (CCRRM), which assesses the performance of 197 countries across 32 structural and dynamic issues. These incorporate a range of interconnected factors crucial to a country’s resilience, such as:

- physical exposure to weather-related events

- political stability

- economic power

- resource security

- civil unrest

- poverty

- the human rights situation

- conflict

- strength of infrastructure

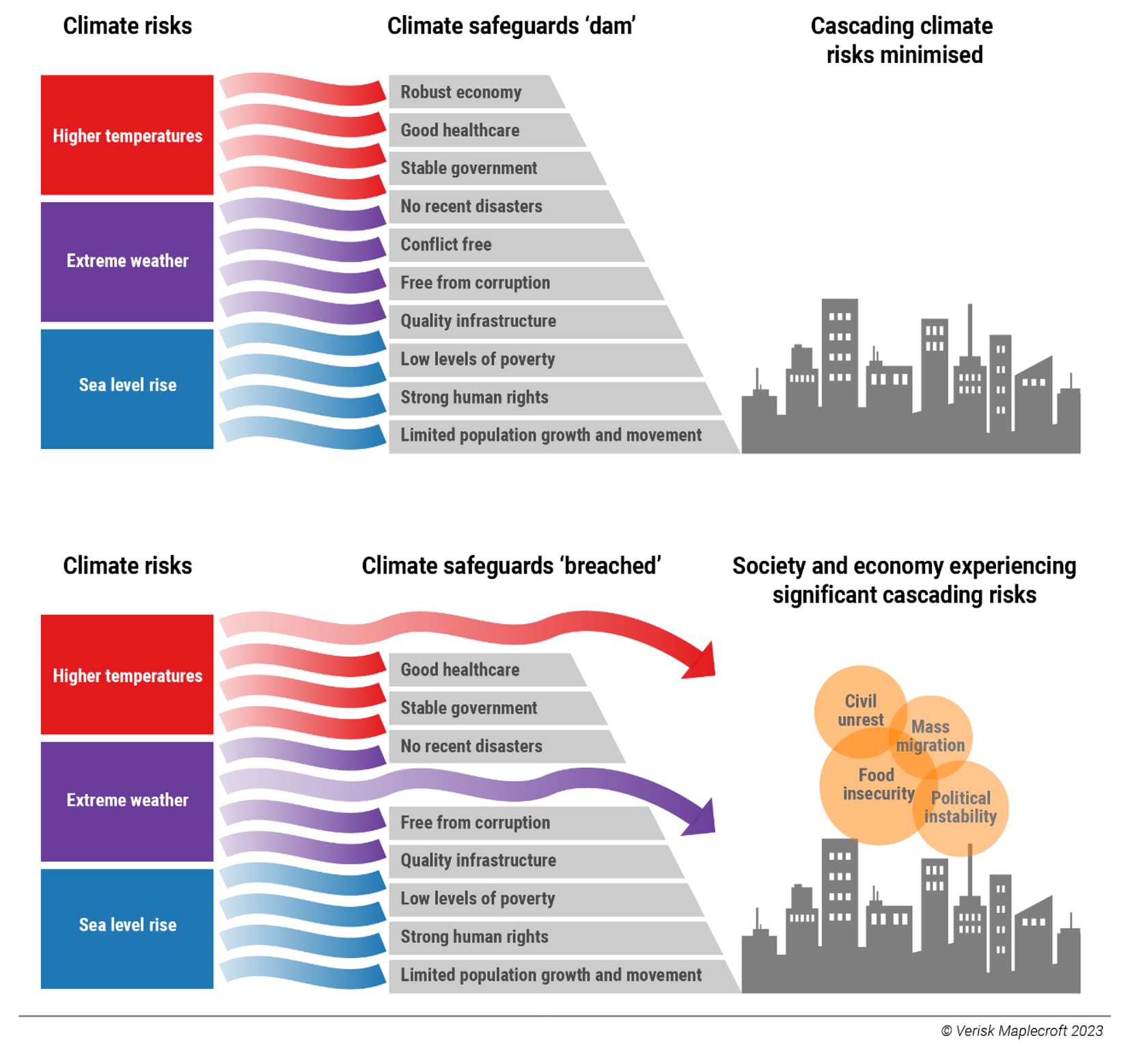

Think about each factor as a block in a dam: the more blocks a country has in place, the stronger the protection. But if the blocks start to erode, the whole structure is undermined, magnifying the potential for ‘cascading climate risks’ to break through and overwhelm a country.

Determining the shared characteristics and differences between countries across five sets of indicators (climate change vulnerability, economic development, health, political risk and social issues) enables us to identify which countries are best placed to manage these risks. We then use this data to split the world into three groups that we’ve termed ‘resilient’, ‘precarious’ and ‘vulnerable.’

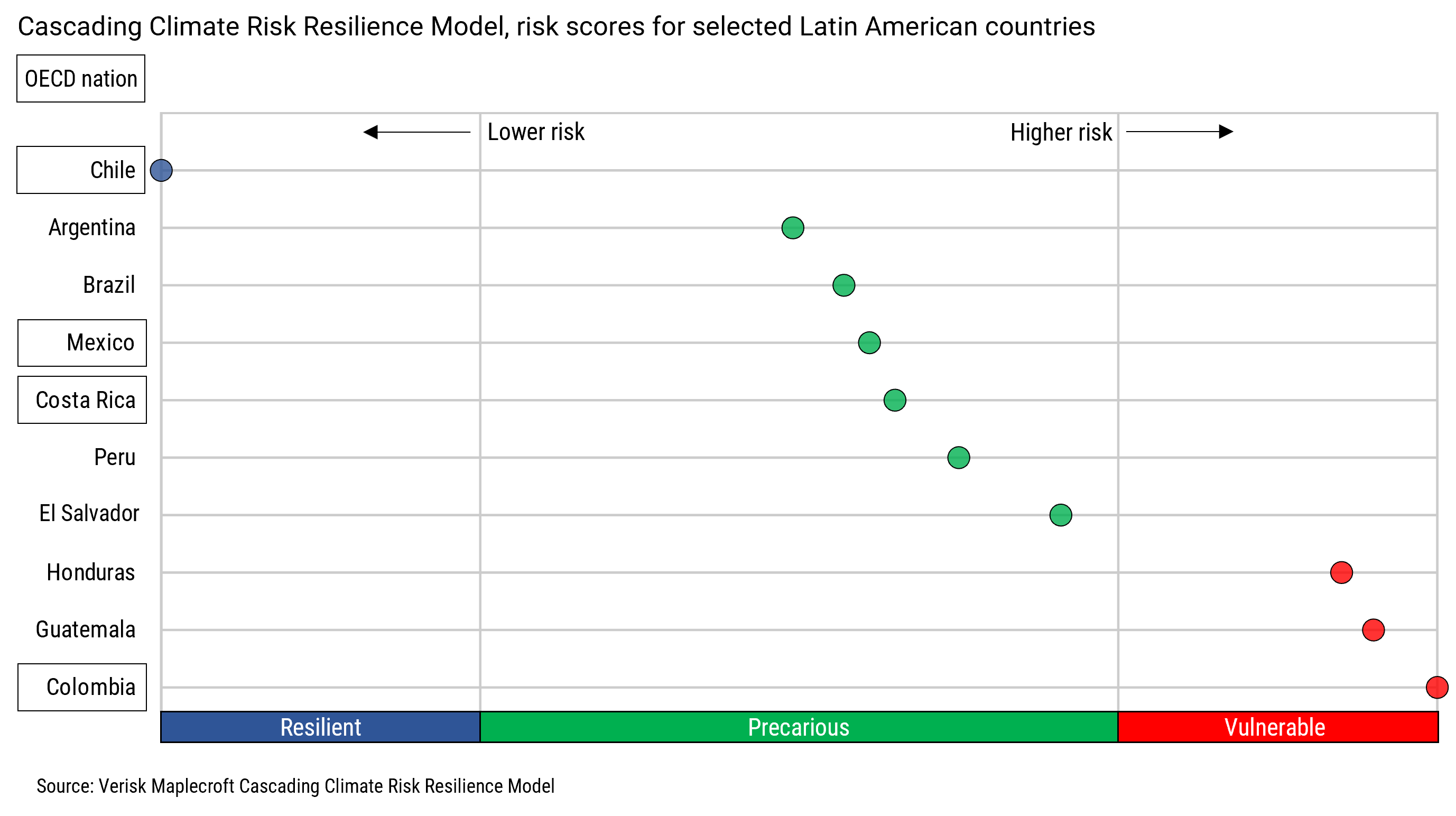

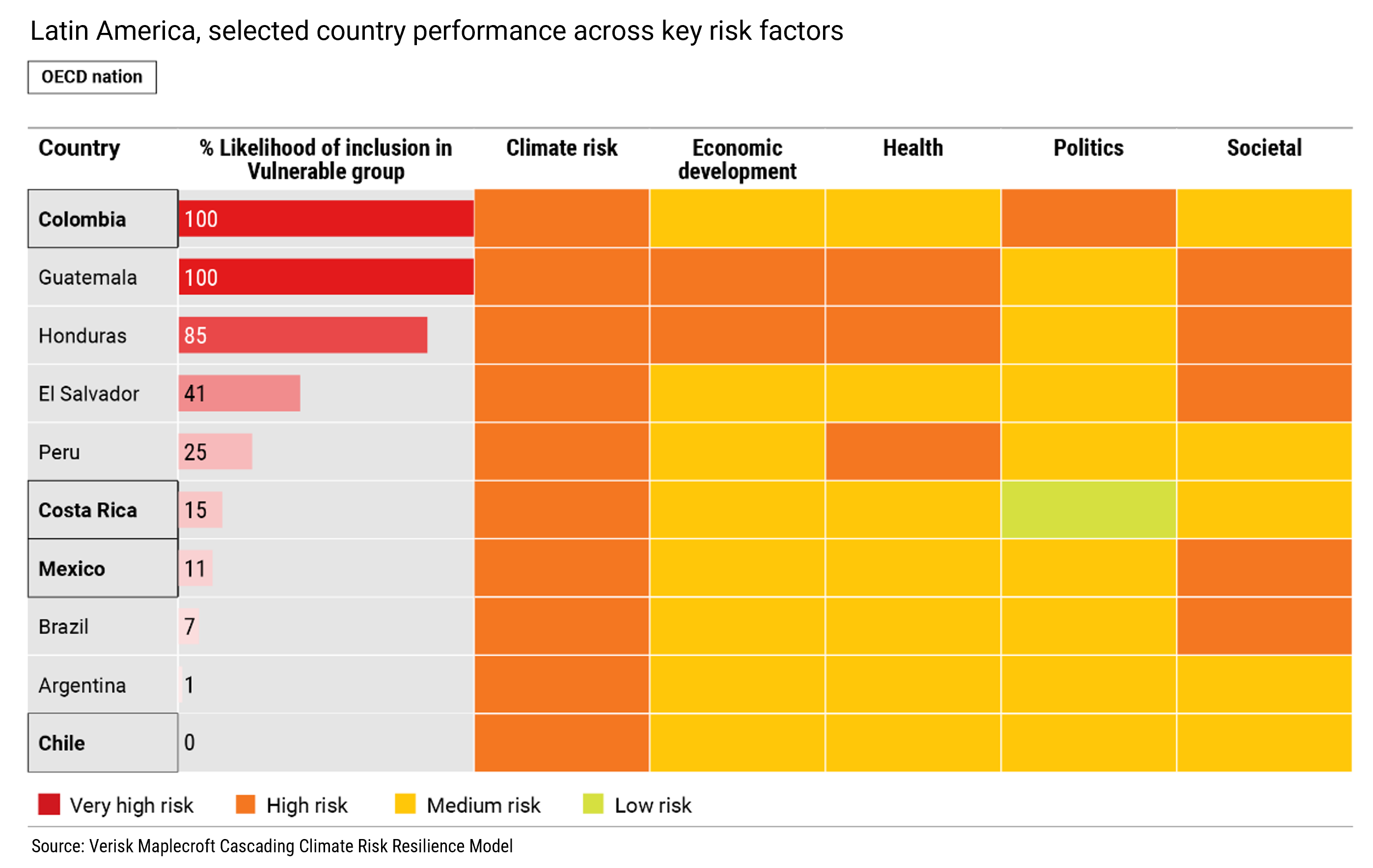

It is no surprise that our ‘resilient’ group predominantly includes the world’s wealthier countries, including 33 of OECD’s 38 member countries. The institutional and economic strength of these countries enables them to better contain the primary impacts of climate change. However, among OECD countries, Colombia, Israel, and Turkey sit within the ‘vulnerable’ group and face significant challenges, while Mexico and Costa Rica fall into the middle ‘precarious’ category.

In the chart below, we show how OECD member countries in Latin America are performing, alongside those countries that are seeking accession to the OECD. We also show Central America’s Northern Triangle, which is already experiencing secondary climate impacts and is (as a result) the source of much northward migration.

Tipping points?

Resilience is dynamic; countries can shift between clusters. For example, small changes across these five categories can propel nations towards improved performance or drag them backwards.

Most OECD member countries categorised as ‘precarious’ or ‘vulnerable’ in Latin America fit squarely into their categories. The majority face high exposure to physical climate risks; in Colombia’s case, these are compounded by structural challenges stemming from the legacy of internal conflict.

Central America has its own share of challenges. On top of physical climate risks, some nations’ poor health outcomes, in addition to issues around democratic governance, rule of law, and human rights, are further hampering their ability to respond to increasing climate-related challenges.

Cascading climate risks are not static. As the chart above shows, of the three major South American economies seeking OECD accession (Argentina, Brazil, and Peru), Peru has the greatest chance of falling into the ‘vulnerable’ category. The model shows Argentina and Brazil are relatively more stable, but also face structural and dynamic challenges.

Focusing on the secondary threats emanating from climate change is one way to improve future resilience and protect hard won economic and social gains.

So, does standing still mean falling behind?

Governments and businesses are struggling to understand these risks and factor them into scenario analysis and risk management approaches. This needs to change. For Latin America, the time for action is now.

Of course, it’s difficult: ‘cascading risks’ are unpredictable, manifest differently in different locations, and hinge on a host of factors. Additionally, governments and businesses are often focused on nearer-term issues, which can blind them to the bigger picture.

But, for companies, getting ahead of these risks before they snowball into direct ESG threats to operations, assets, and investments is crucial. And prioritising stress-testing resilience, business, and investment strategies against high-impact scenarios will enable both organisations and governments to identify, map out, and prepare for these longer-term threats.

Only by fostering better co-operation between governments and multilateral institutions can we achieve our mutual goals. And, as always, the first step is recognising that the risks are there in the first place.

This piece was first published on the OECD’s Development Matters Blog on the 4th October 2023.