It's official, Australia is the next country to adopt a modern slavery act. This week, the Minister of Justice, the Hon Michael Keenan MP, published the government’s preferred option for the new law. His proposal is a tighter, more effective version of the UK’s Modern Slavery Act, introduced in 2015. The Australian law will have more teeth, albeit not very sharp ones.

Since February, when the attorney general George Brandis first opened the inquiry into establishing a modern slavery act, there’s been no shortage of advice given to the federal government’s joint standing committee. Global businesses, investors, NGOs and academics made 173 submissions, many of them reflecting on lessons learned in the UK.

These stakeholders now have a chance to influence the final shape of Australia’s anti-slavery law in a second consultation. The debate will inform what stays and what goes – and what is added – to the government’s preferred option, by the end of the year.

What will the final law look like? Business can expect a simpler mandatory reporting framework than in the UK, but coupled with more scrutiny. A tussle is likely with NGOs over undecided issues such as which companies have to report and what penalties, if any, should be payable for not complying.

Lawmakers are unlikely now to adopt the more radical requirement of mandatory human rights due diligence. Nonetheless, the global consultation they have inadvertently hosted is pushing the goal of a single standard up the global agenda.

Naming and shaming the boss

For company directors, Australia’s modern slavery act will get uncomfortably personal. Their name and signature will be on the annual statements they have to publish. These statements ‒ at the heart of the concept of disclosure laws ‒ explain the steps a business takes to ensure their organisation and supply chain is slave-free. Boards have to approve the statements; directors, or their equivalent, have to sign them.

It is arguably this signature that single-handedly pushed modern slavery from the bottom to the top of board agendas in the UK. Australian CEOs will be no less sensitive than their British counterparts, when their own reputation, as well as that of their company, is at stake.

Company threshold set at 100 million dollars

Expect civil society to push for more companies to be in scope. Currently, the government is proposing that corporations and funds with total annual revenue of more than AUS100 million are required to report. This will pick up the big players such as Wesfarmers, Woolworths and Rio Tinto, which all made submissions on the law. In the current proposal, smaller companies below the threshold can ‘opt in’.

There is merit to the argument that it is better to start with a smaller pool of the most powerful companies that can trigger change through their supply chains. The UK threshold captures more businesses as it is set lower, at GBP36 million (AUS61 million); however, only a minority have actually complied. Civil society will push for wider coverage, arguing this is essential to drive improvement across supply chains simultaneously. As no one gives their best offer at the start of a negotiation, there is probably room for the threshold to fall.

More scrutiny, but no fines

It was always unlikely that Australia would impose fines on businesses that chose not to report, but NGOs will no doubt push lawmakers to toughen up the penalties for non-compliance.

Currently, the consultation proposal notes that the government will monitor compliance and that businesses that do not report may be subject to public criticism. This intriguingly hints at the possibility of the official ‘outing’ of non-compliers, like Brazil’s once-effective ‘dirty list’. If the government decides to name and shame companies that don’t report, and puts this task in the hands of an independent anti-slavery commissioner, the costs of non-compliance would sharply increase, particularly for those companies with products or services that are consumer-facing.

Two other simple measures will increase scrutiny of businesses that do and do not comply with the act. First, the government is going to clearly mandate the reporting criteria. This will standardise and simplify reporting and level the playing field for businesses in scope. Second, all statements are going to be hosted in a free and accessible registry. As a result, investors, NGOs and consumers will be able to easily analyse and compare disclosure statements. This means more exposure for companies doing the right thing – and also, for those that do not.

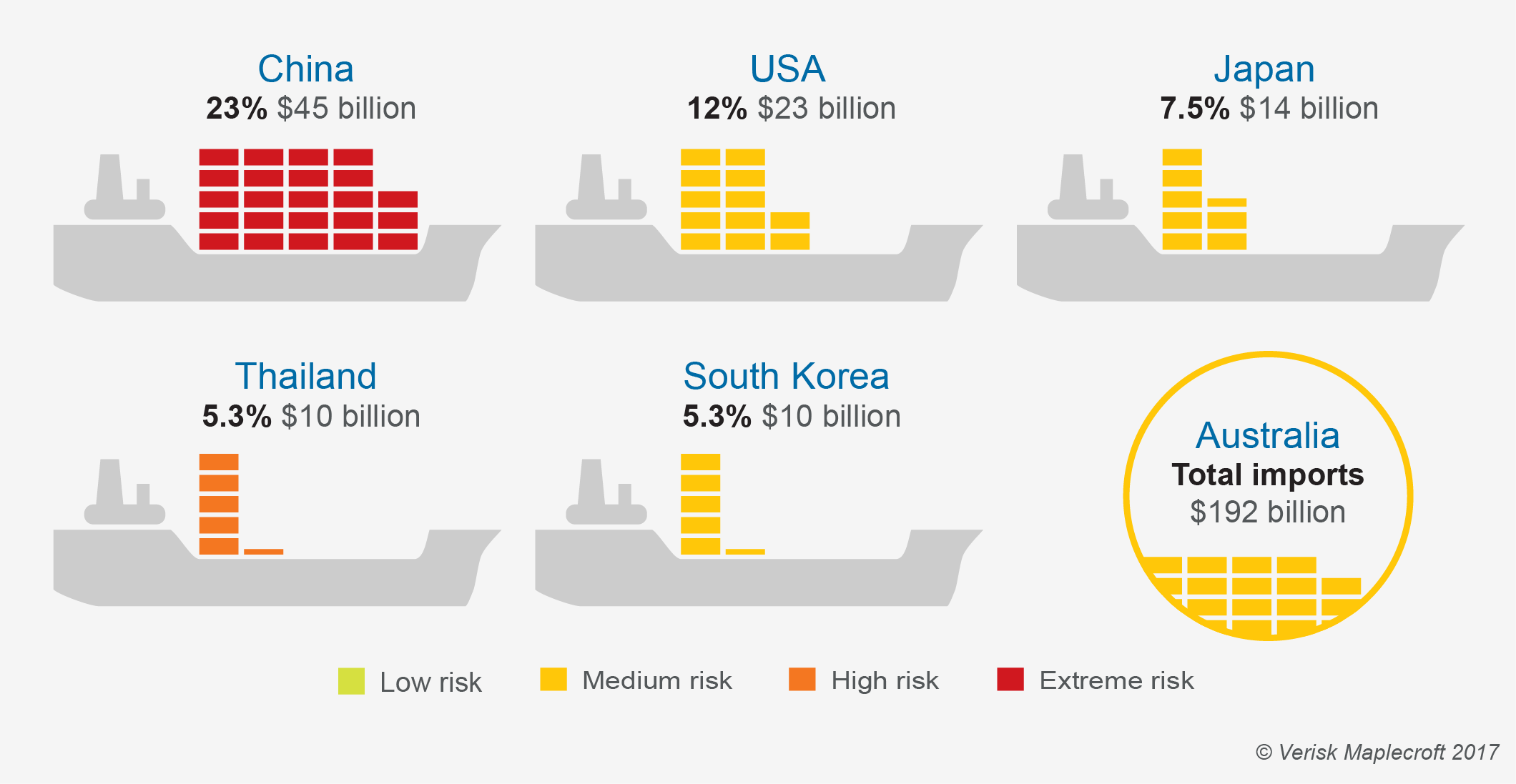

As the visual above shows, our Modern Slavery Index reveals that Australia, and most of its major import partners, fall into the higher risk categories for modern slavery. This underlines the considerable human rights risks impacting Australian business, including those covered by the country’s forthcoming anti-slavery law, expected in 2018.

What's missing?

Absent from the government’s proposal is the concept of mandatory human rights due diligence, which was introduced this year in laws in France and the Netherlands. The inquiry committee concluded that it would place too great a burden on Australian business at this point. That may well be true; and, requiring companies to report on their modern slavery due diligence is a step in the right direction. But, the shift toward laws that make human rights due diligence a compulsory standard is inevitable. For business, it is better to accept this reality and get ahead of the game.

Nor does the government propose to hold companies responsible for due diligence failures abroad. The principle of ‘extraterritorial’ scope means that companies are held accountable in Australia if their negligence results in human rights violations committed by their partners or subsidiaries, regardless of location. Given the lack of appetite for punitive penalties for non-compliance, Australia is far from ready to consider this route.

Driving the global human rights agenda

Australia’s modern slavery act is tough enough to drive modern slavery to the top of the business agenda in the country. With better scrutiny of statements and senior level accountability putting CEOs’ reputations on the line, the law will increase the benefits of exposure and the cost to business of not complying. That is a significant achievement. Publishing the list of companies that do and do not report would leave no place to hide for non-compliers.

Intended or not, the law will also stimulate demands for alignment around a global standard for human rights regulation. The consultation process has acted as a global forum for business, civil society and government to discuss the merits of different types of human rights legislation. Many stakeholders have called for mutual recognition by countries of disclosure statements. No one wants business to have to report against multiple standards, though views about what a single standard might look like diverge. While Australia’s lawmakers are firmly focused on a domestic solution, there is, however, no doubt that they are also playing a pivotal role in shaping the development of human rights legislation globally.