Where should the world’s waste go?

Investment in circular economy will reduce costs

by Will Nichols,

China steps away from its role as global garbage collector

Throwing something out kicks off a complicated, global process. Many waste streams, including plastic, are difficult to deal with because the necessary infrastructure is not in place. And, even if the object can be recycled, there may not be a market for the treated material. Material that cannot be sold or treated is either landfilled or sent abroad.

But as long as China was willing to buy these exports, Western nations had no incentive to invest in their own treatment facilities.

So, when China banned imports of 24 varieties of solid waste on January 1 2018, including a host of plastics, global waste flows were overturned. Another 16 categories were prohibited from the end of the year and another 16 will be from the end of 2019.

Banning so-called ‘foreign garbage’ aligns with Xi Jinping’s ‘Beautiful China 2035’ policy amid a broader push towards a greener economy, but by 2030 will create an 111-million tonne mountain of waste that will need to be treated – much of it plastic.

Are other countries following suit to ban waste imports?

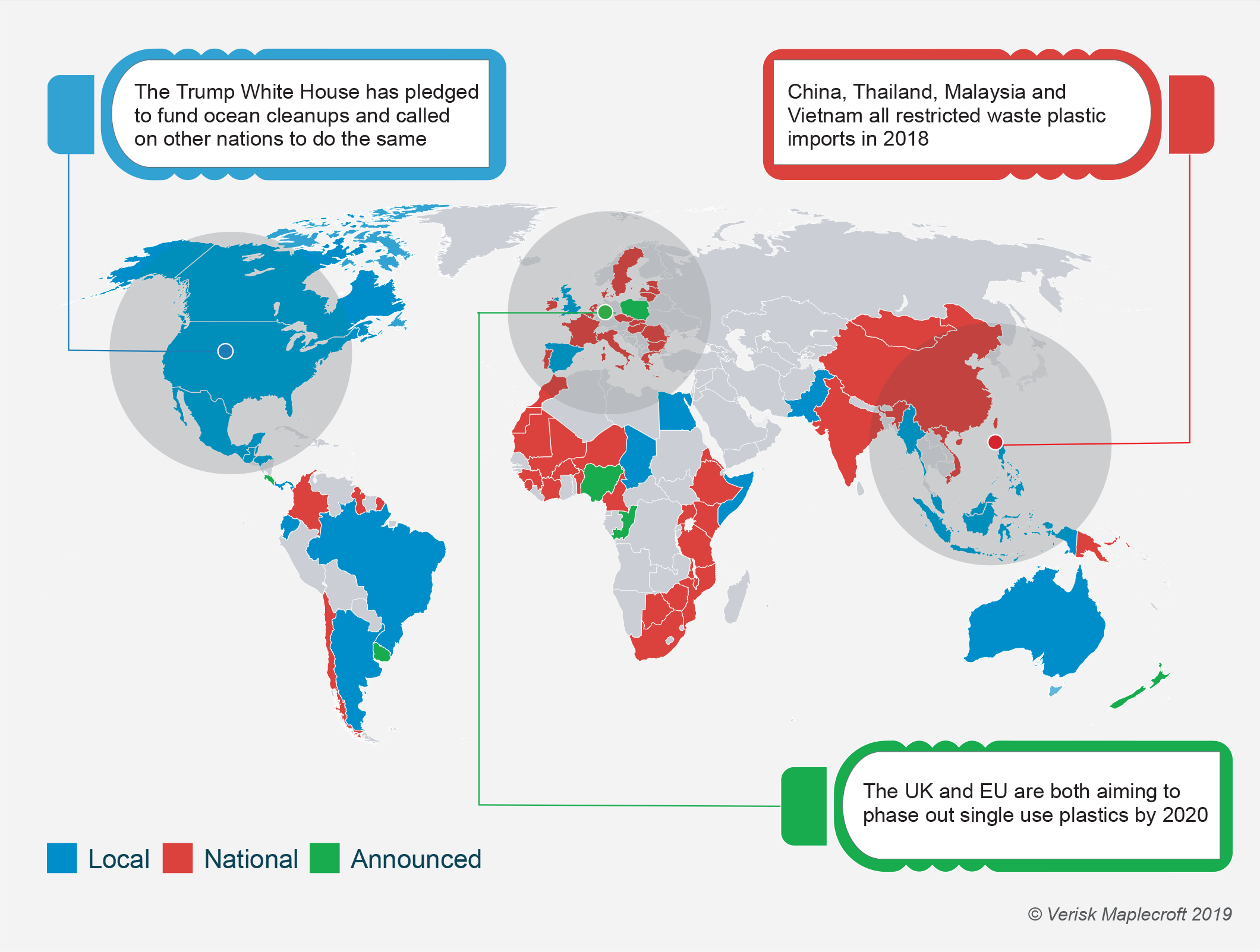

Other waste importing countries have also moved to limit the material they accept, ban it outright, or return waste. Thailand is set to ban foreign plastic waste from 2021, Vietnam is due to follow in 2025, and Malaysia is weighing up longer term options after issuing a temporary halt to imports in 2018. This year, the Philippines came close to causing an international incident by pressuring Canada to repatriate waste falsely labeled as plastic scrap. It was no surprise when, in May, almost all the world’s nations, with the US a notable exception, signed an amendment to the Basel convention that would restrict shipments of hard to recycle plastic waste to developing nations.

Meanwhile, companies face growing domestic pressure to deal with waste, notably plastic: more than 60 countries and a host of regions are introducing – or have already brought in – legislation aimed at reducing the use of plastic bags and other single use plastic materials.

Waste disposal starts at the company-level

Companies’ responsibility for their waste does not end when it is collected. Pushing materials overseas where they may not be disposed of properly, heightens the risk that companies will see branded bottles washing up on pristine beaches. Plastics are the most high-profile source of reputational risk related to waste, given consumers, politicians and investors are all highly engaged in the global marine pollution problem. But interest in other streams is growing, which means companies need a solution to avoid brand damage and regulatory action.

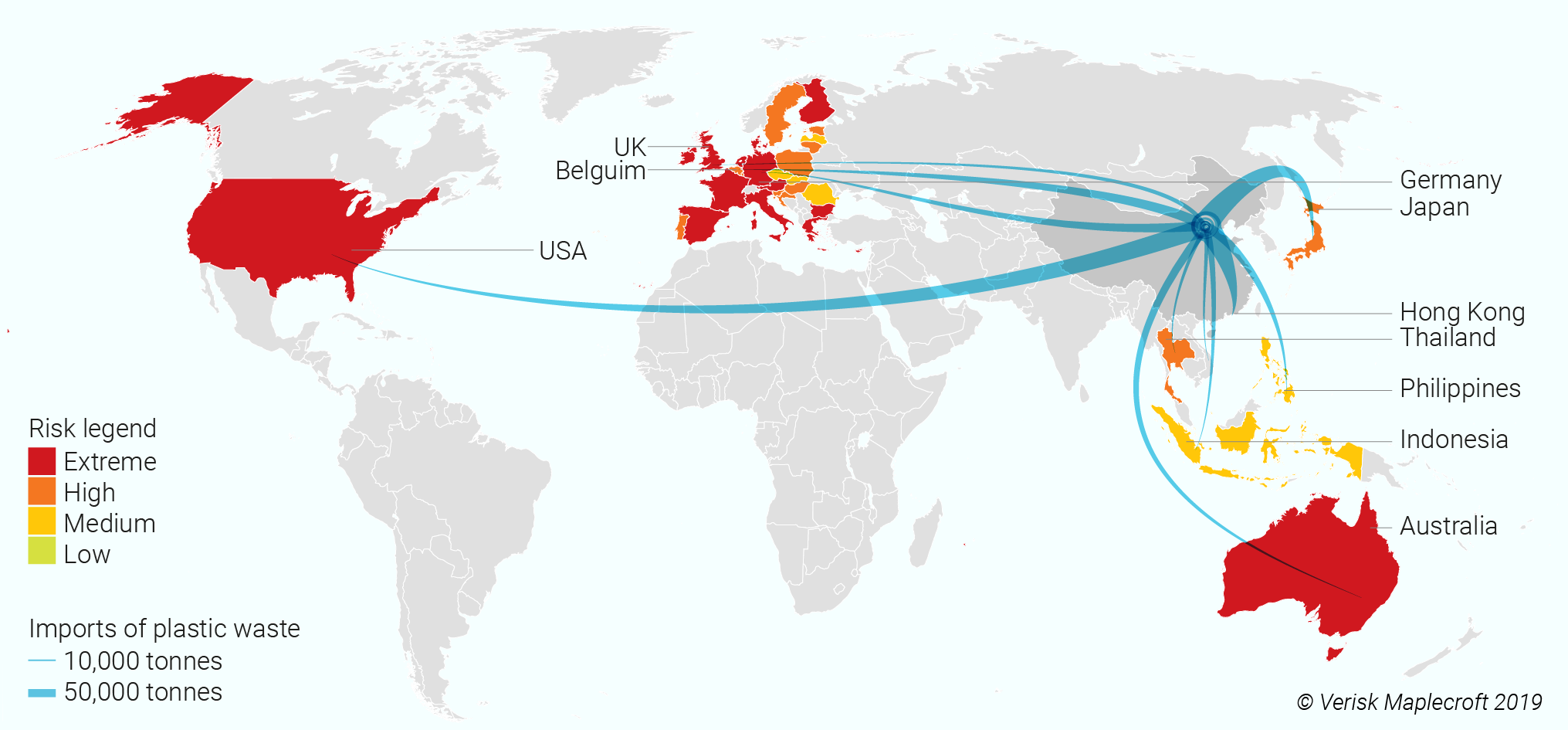

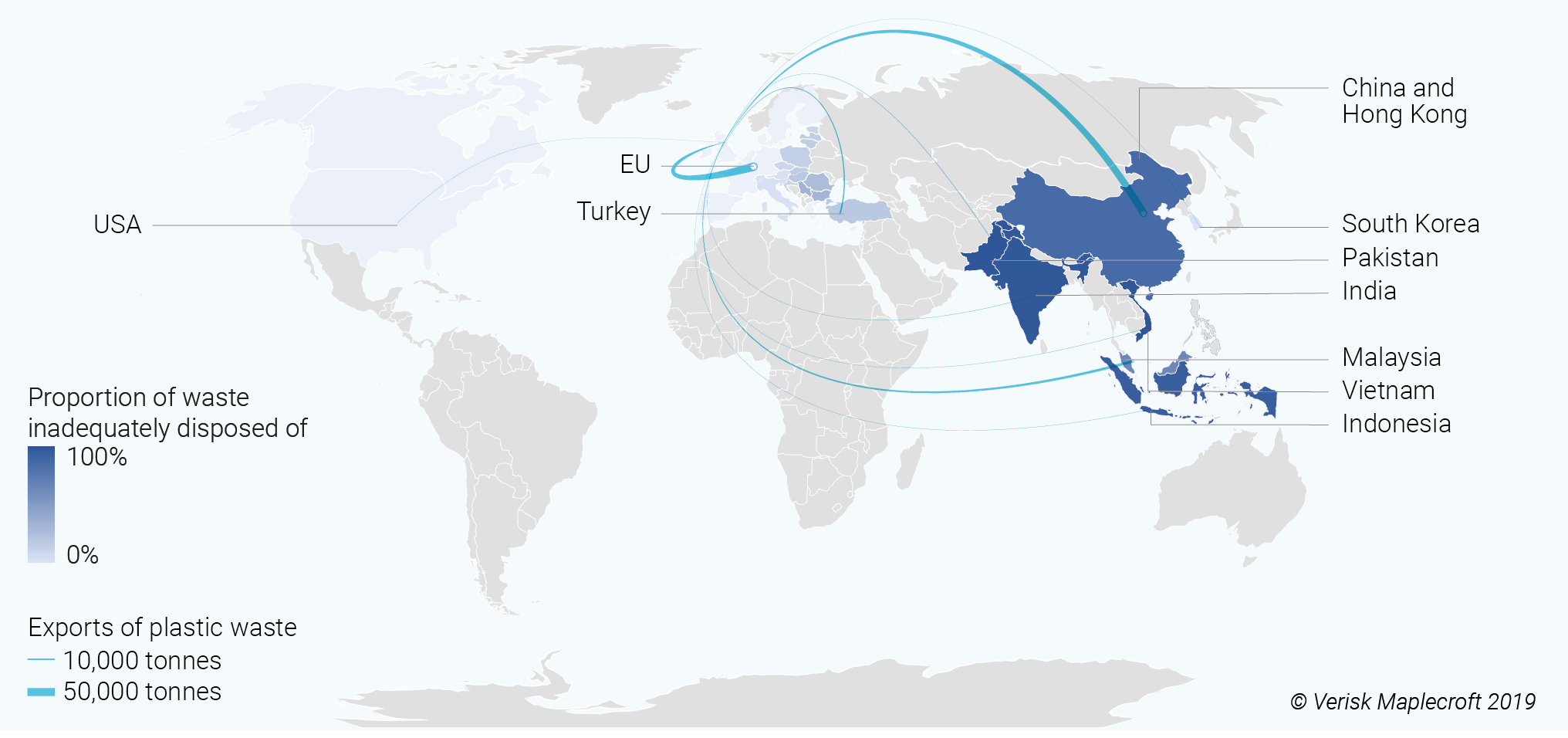

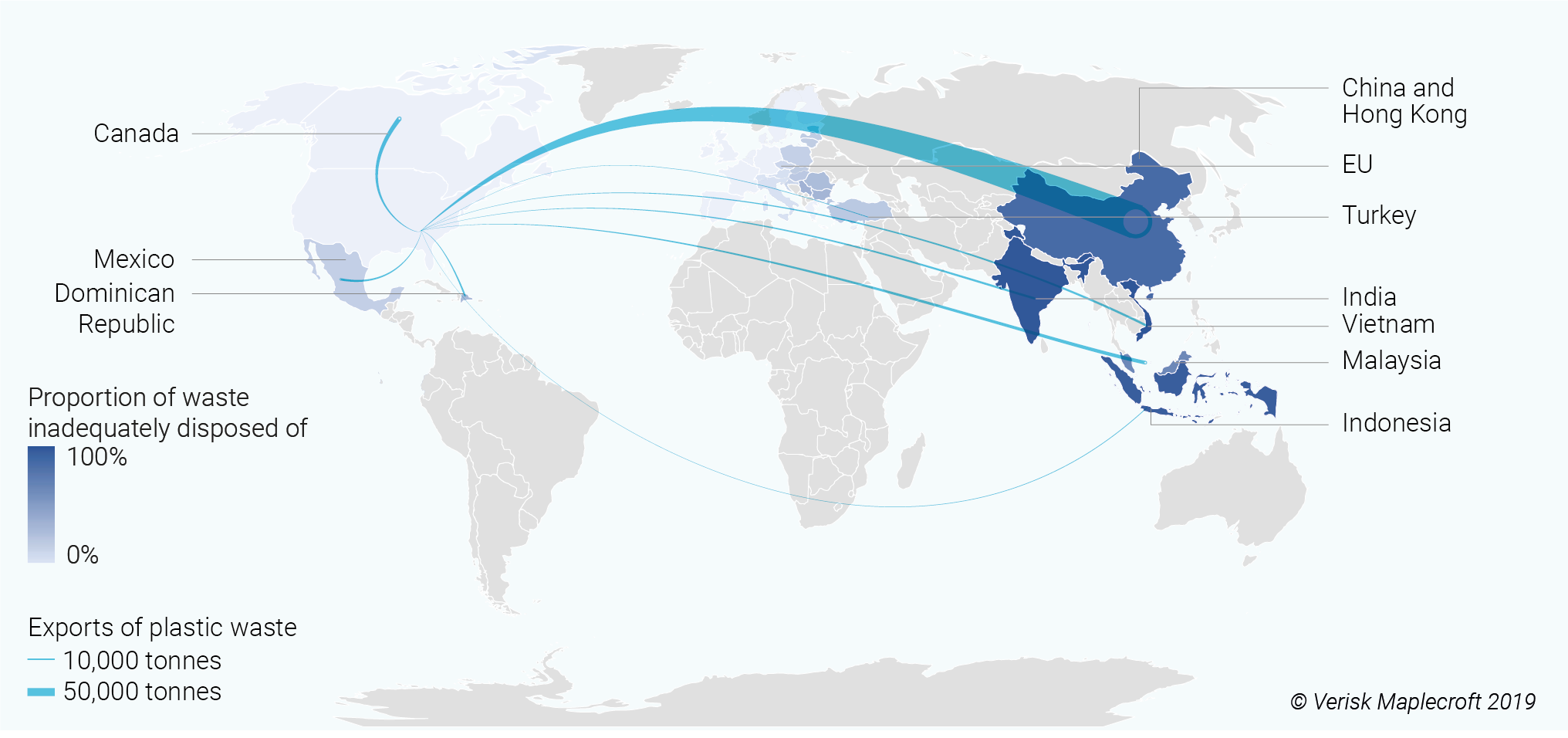

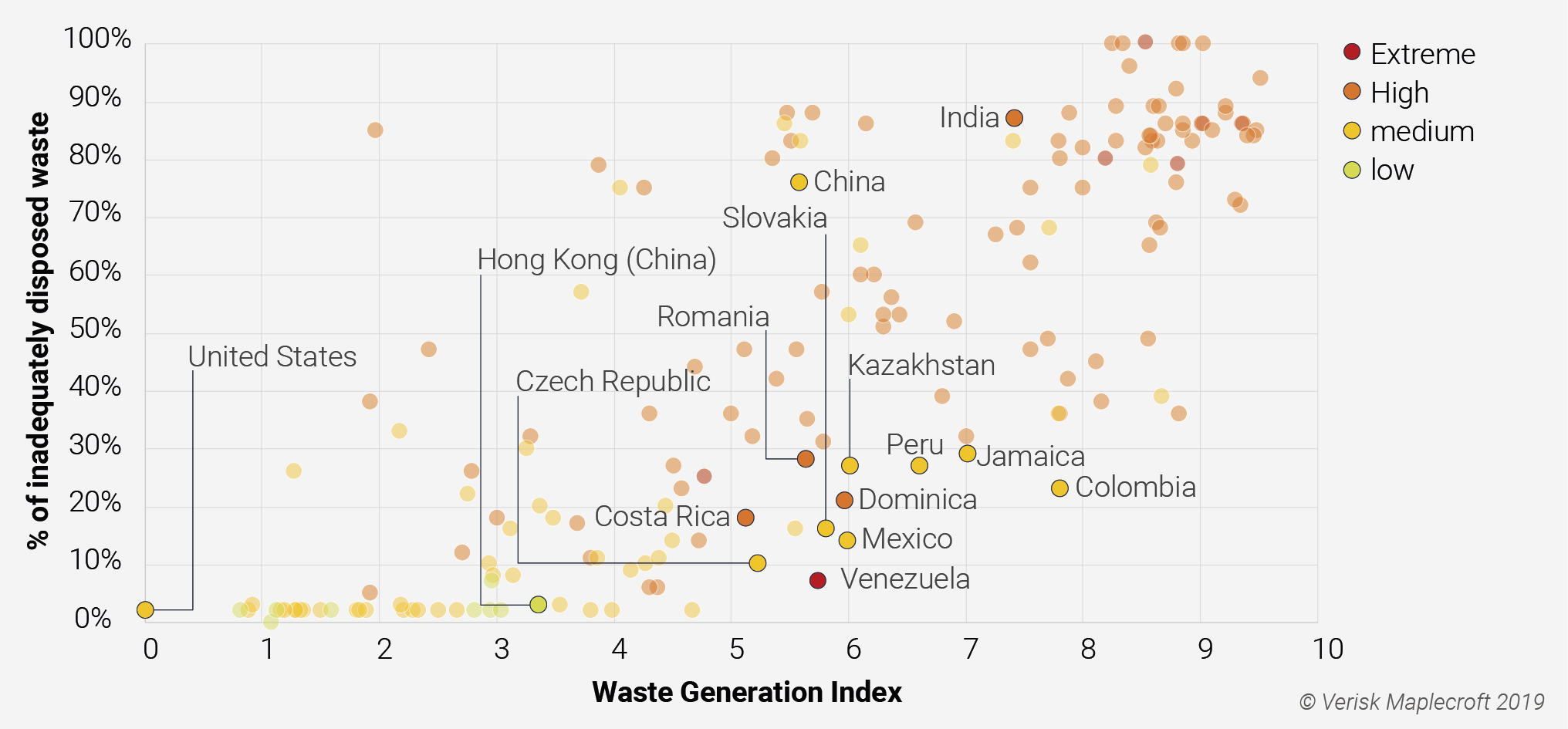

Using the Waste Generation Index (WGI) we can see that those countries exporting large quantities of waste are also producing large volumes. Following China’s ban, major waste exporters like the EU, US and Australia will not be able to manage much of the plastic waste they generate domestically without concerted investment in treatment infrastructure.

Upgrading infrastructure comes at a high cost to governments and in many developed nations responsibility has been passed to the private sector. So, companies, or groups of companies, could have to finance their own disposal facilities and processes.

New infrastructure and new destinations for waste are a necessity

In nations where infrastructure is already struggling to cope with waste management pressure, finding new destinations for waste will be paramount. But taking the UK plastic waste exports as an example, large swathes are already going to countries set to introduce import bans.

The map below, pairing the top 10 export recipients and using data from our Recycling Index, shows that other plastic waste export flows are going to countries where large amounts of waste are inadequately dealt with, increasingly the potential for mismanaged waste to become a reputational issue.

Germany’s export flows for its top 15 partners look strikingly similar, but higher proportions of plastic waste exports to eastern Europe and Russia. Corporations in Germany whose plastic waste is exported are less exposed to that waste being mismanaged than those in the UK.

US plastic waste exports to China vastly outweigh those of the UK or Germany, which elevates the risk of waste being mismanaged when it is diverted from China and other countries with import bans.

While Colombia, Ecuador and El Salvador manage waste better than many of their South East Asian counterparts, they do not have the infrastructure to cope with an exponential increase in plastic waste.

Other mooted destinations have even poorer records: Ethiopia mismanages 94% of its waste, Senegal 84%, and Bangladesh 89%.

Where does the waste go now?

With the new global pact, China and other countries refusing to take waste, and many governments reluctant or unable to invest in waste management upgrades, corporates will need to find their own solutions.

One option is new destinations for waste exports. The graph below highlights that many countries that manage waste well, also produce a lot of it. Nations that not only produce little waste, but are also adept at dealing with what they do generate, may be better bets for companies looking to dispose of waste responsibly.

Countries with at least a medium risk score in the WGI and below 30% waste inadequately disposed of include a host of Latin American and Eastern European nations.

However, the graph also shows the potential risk investors would face in financing new waste infrastructure in these nations. Using the Fiscal Environment Index as a proxy for sovereign credit risk it is clear that low risk countries are also big waste generators. Investors could consider medium risk nations such as Mexico, Peru, Colombia, Slovakia or the Czech Republic, but would do well to steer clear of Venezuela, an extreme risk country, despite its low WGI score and well-managed waste.

Investing in circular economy will help to reduce costs

Any change in waste management process will be difficult without forcing up operational costs and product prices. We can expect companies using large amounts of packaging, such as logistics or retail, as well as ICT firms using plastic in their products to be most affected.

However, investing in circular economy solutions to should insulate companies against growing customer and regulatory pressure (see map), while aligning with benchmarks like the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). All of which will please investors concerned about a companies’ impact on the environment.

Some companies are already transitioning ahead of the curve.

Starbucks, Unilever, Evian and McDonald’s are among those that have made high profile switches away from plastic to alternative materials.

This trend will drive innovation and investment opportunities in materials design, processing and disposal and could eventually result in lower cost alternatives such as bioplastic.

The scale of investment needed to realise a circular economy will require partnerships with rivals and across sectors. But companies failing to act in the face of rising political, consumer, and shareholder concern will be consigned to the scrapheap.