What sovereign ESG investors could have looked out for before Russia’s war against Ukraine

by James Lockhart Smith,

It’s not just money sovereign emerging market asset managers have lost because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. With stakeholders and observers asking why funds were significantly exposed to Russia in the first place, the credibility of their overall ESG commitments has also been thrown into sharp relief. This miscalculation doesn’t entirely land at the managers’ feet though. The capital markets ecosystem as a whole was drastically wrongfooted by the war, as shown by a slew of retrospective reassessments of Russia by banks, ratings agencies and index and data providers.

There are no easy answers here. Not every poor ESG performer is going to invade its neighbour. In that sense, events since February 24 have been extreme and idiosyncratic. And if Russia is now unacceptable on ethical grounds, so are many other key constituents of EM government portfolios. Any reassessment of the trade-off between norms and returns in EM investing would need to look far beyond Russia alone.

Nonetheless, as we show below, since 2017, Russia has been an exceptionally poor performer in our Sovereign ESG Ratings, and certainly one of the worst among major emerging markets. So poor, in fact, that some of the human rights and governance indicators that would otherwise be affected by the invasion don’t now have any further to fall. In essence, the alarm bells have been ringing for some time.

Markets missed Russia’s ESG red flags in the run-up to the invasion

Setting our data against market behaviour in recent years, we see that in contrast to their approach to other former Soviet Union (FSU) states in Eastern Europe, investors turned a blind eye to Russia’s latent ESG risks. Until, that is, February 24, when they couldn’t anymore.

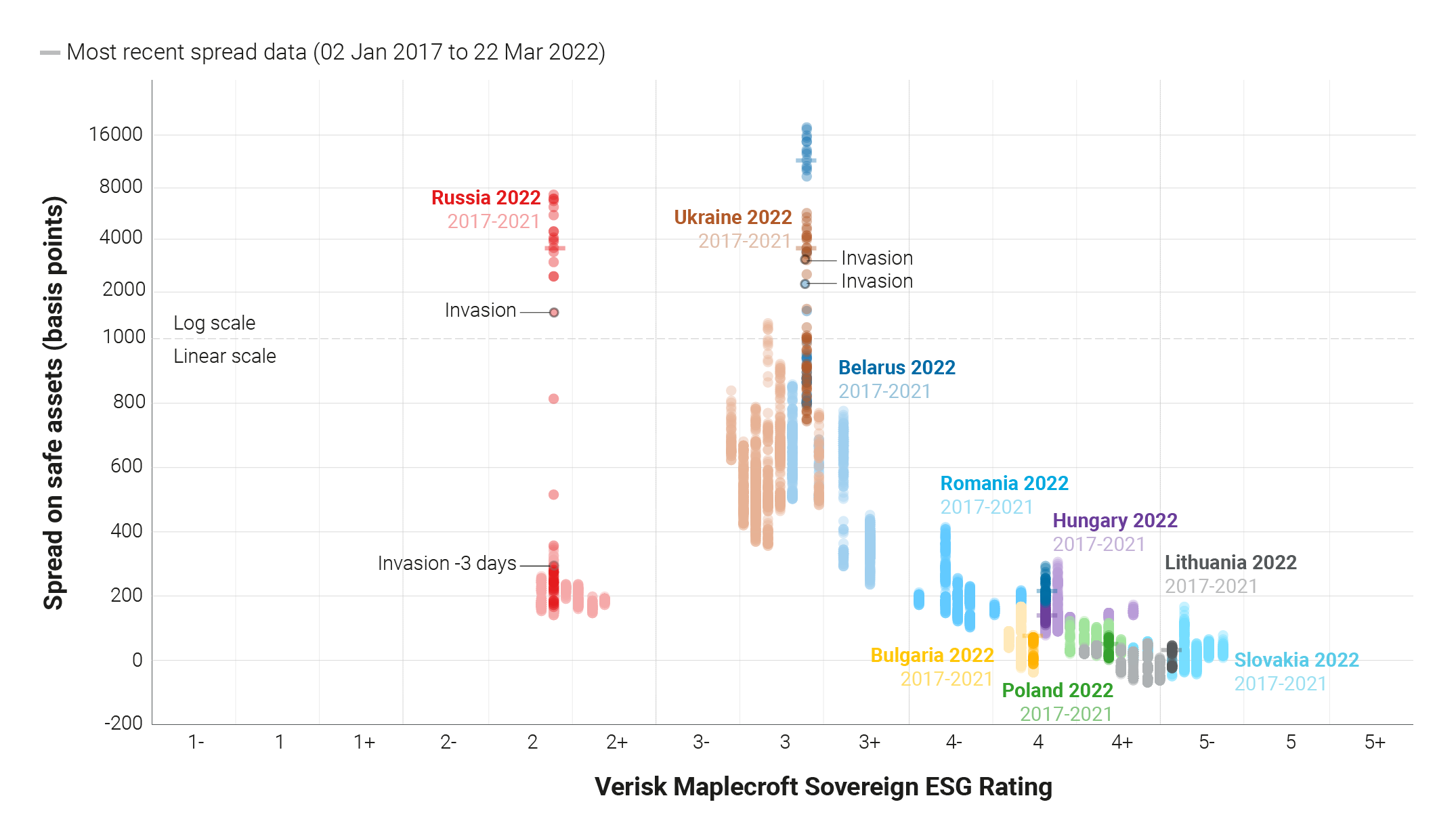

As shown in Figure 1, on the eve of the invasion Russia was already the standout worst among European FSU states in our Sovereign ESG Ratings, which we released in early February. Scored across 37 issues within 9 ESG dimensions, Russia’s headline ESG score performer of 32/100 and accompanying ESG Rating of 2 on our 15-point scale (ranging from 1- to 5+), trailed Belarus and Ukraine (both scoring 52/100), the next-worst performers, by a full 20 points, and FSU members of the EU by much more. This placed it on par with much less wealthy emerging and frontier markets such as Algeria, Angola, Peru, as well as the historically more autocratic Saudi Arabia.

You might expect these considerations to have affected market pricing given our research findings on the materiality of sovereign ESG. However, while spreads are of course also shaped by a range of macroeconomic factors, many of which played in Russia’s favour, Figure 1 nevertheless also reveals that the country was the outlier in an otherwise straightforward association between ESG performance and borrowing costs – until, of course, the invasion caused its spreads to skyrocket.

Already bad, Russia’s ESG rating will likely get worse

Some of our clients have asked us whether we will downgrade Russia further in response to its invasion of Ukraine. The answer is: it depends. On one hand, the country already scores so poorly on several metrics that it has little further to fall. On the Governance pillar, for example, Russia received the lowest possible G1- rating before the invasion – one that landed it among capital market pariahs such as Venezuela, Iran and Turkey, as well as emerging markets with recent histories of instability like Egypt and Thailand.

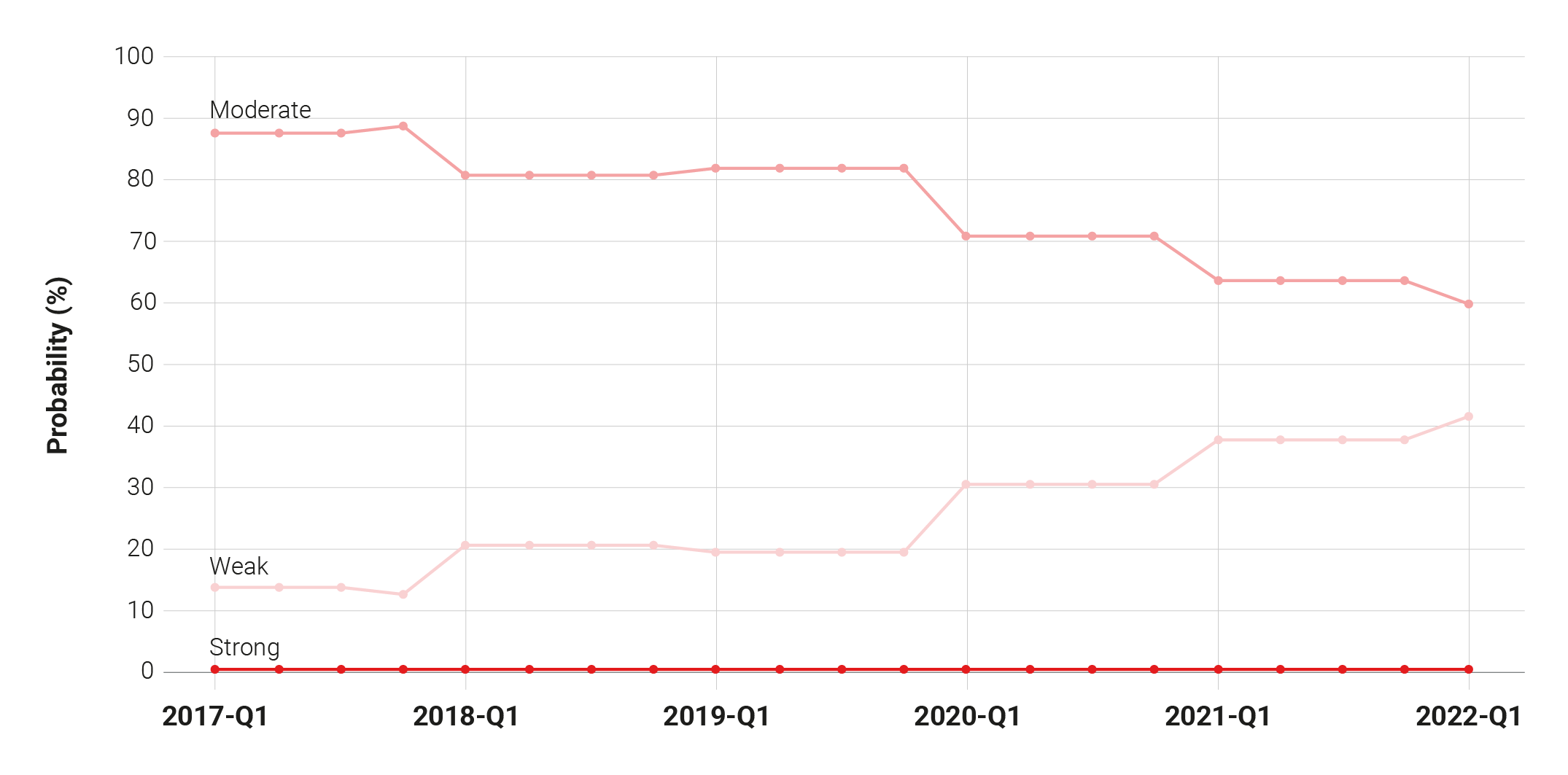

While Russia has historically performed slightly better in the Social pillar, receiving a rating of S2+ in 2022-Q1, similar to other major emerging markets such as China, South Africa, Turkey, Malaysia and the Philippines, its human rights profile worsened in the years preceding the Ukraine invasion. In particular, Russia moved steadily towards a tipping point that, if crossed, would see it register as ‘Weak’ in the Human Rights dimension of our sovereign ESG risk framework, as shown in Figure 2.

Moreover, the country already registered as high-risk on our Freedom of Assembly Index and extreme-risk on our Security Forces and Human Rights Index – two of the four indices captured in this dimension – with a near-zero score on the sub-indicator for the latter that registers actual killings and other grievous violations. Given that we attribute such abuses to states not just domestically but when they are operating outside their borders as well, this metric would have been directly affected by the invasion – except that the score has practically nowhere left to go.

Nevertheless, we do expect Russia’s sovereign ESG rating to fall further in the coming quarters, potentially by a full notch. The most immediate driver of change is likely to be the effect of post-invasion politics on the country’s human rights performance, in particular the rapid curtailing of freedoms as Moscow seeks to hide the character of the war from its citizens, as well as other rights abuses committed by troops during the invasion. This will likely push the country into the Weak cluster on this dimension, as detailed above. Furthermore, the massive economic hit from sanctions is likely to cause backpedalling across multiple other areas of ESG, including environmental policy.

And finally, Russia’s Governance pillar could also erode even further. While it is already in the worst-performing category on the Sources of Instability dimension of our sovereign ESG risk framework, the index scores that make up this dimension have actually improved somewhat over the last 5 years as the Kremlin has clamped down on opposition and consolidated its control over all branches of government. That trend may now reverse, especially if civil unrest continues to intensify as opposition to the invasion builds and Western sanctions exacerbate the cost-of-living crisis.

Learning the hard way

No-one could have drawn a direct line between Russia’s poor ESG performance and its invasion of Ukraine: the job of sovereign ESG ratings is not to predict war. But the episode has still been a hard lesson in sovereign ESG at the extremes. It’s not clear yet whether the crisis will trigger any wider rethink of industry approaches to high-risk emerging markets or be dismissed as a one-off. However, there are many other countries, some of them key markets and core benchmark constituents, with long-standing ESG issues that are habitually accommodated or explained away by the capital markets ecosystem – but which would be thrown into the spotlight should a crisis or extreme event related to them occur. At the very least, robustly integrating ESG factors into the sovereign investment process to identify the risks, and prepare for the worst, should be a priority.