US Xinjiang bill demands full supply chain visibility

by Sofia Nazalya,

On 23 December 2021, President Biden signed the much-anticipated Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) into law, marking a further ramping up of efforts by the US to counter forced labour in China’s Xinjiang province. Following more than a year of delays, the UFLPA was unanimously passed in both the US Senate and House of Representatives. For US companies, the new law’s expansive scope and high evidentiary standard creates arguably the most challenging legal and operational hurdles they face thus far with respect to Xinjiang. The UFLPA’s requirement to “ensure that goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labour… are not imported into the United States” requires a level of traceability that most, if not all companies, are likely to find incredibly challenging without comprehensive supplier mapping and due diligence.

UFLPA, the most sweeping act against Xinjiang to date

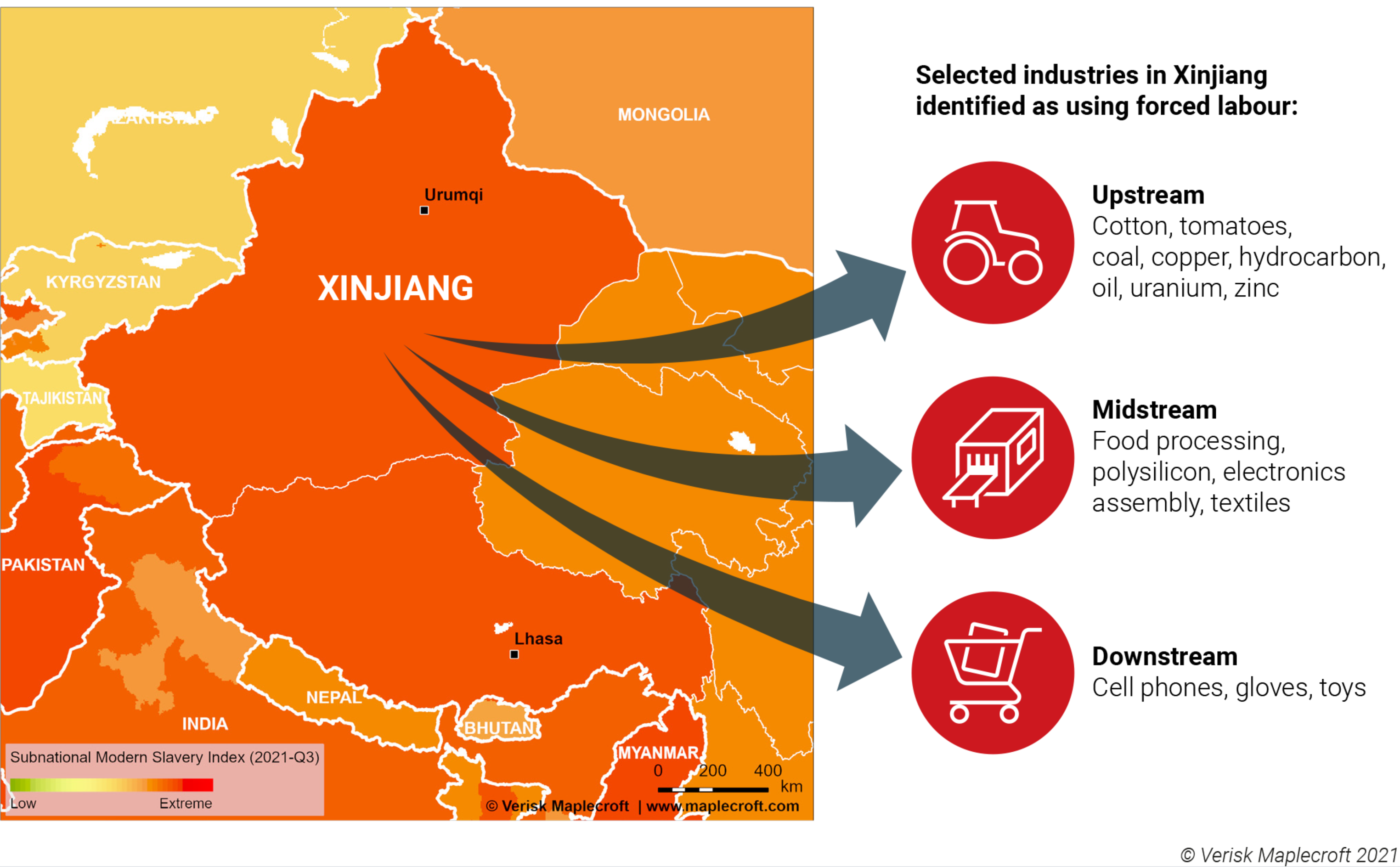

The Act is, to date, the most condemnatory and uncompromising US law against China’s Xinjiang policy, as it establishes a “rebuttable presumption” that all goods produced in Xinjiang are made with forced labour. While previous actions targeted specific products, such as the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) ban on imports of cotton and tomato products in January 2021, the presumption of forced labour region-wide effectively prohibits the importation of all goods arising out of Xinjiang. This will therefore have significant disruptive impact across multiple sectors (see visual below). Companies seeking to continue the import of Xinjiang goods must provide “clear and convincing evidence” that the goods were not manufactured with forced labour, shifting the burden of proof away from customs officials.

The addition of polysilicon alongside cotton and tomato products identified as “a list of high-priority sectors for enforcement” is unsurprising given Xinjiang’s status as a major producer. However, as we have argued in our previous analysis, while enforcement of the Act will be prioritised in these sectors, other industries must also brace for impact. The extension of the forced labour presumption region-wide is likely to make the importation of Xinjiang goods too fraught with legal and operational risks for it to be practical for many US companies.

A key differentiator between the Act and its previous version is the exclusion of the Securities and Exchange Commission disclosure requirements onto US-listed companies. This buys companies more time to assess Xinjiang-linked operations before relocating elsewhere. However, for companies in the apparel and textiles industry, the law is likely to be “old news” given the ban on cotton earlier this year. Most apparel companies are likely to have already implemented contingency plans or are in the process of doing so.

Determining traceability a key challenge for companies

While it is clear that the UFLPA will cause sizable disruptions requiring companies to relocate, or at the very least, strengthen their due diligence processes of their Xinjiang-linked operations, the question remains of its efficacy to prevent the occurrence of Uyghur forced labour in supply chains. Reports suggest that more than half of China’s exports of cotton semi-finished products are exported to Asian garment manufacturing hubs, where international intermediary factories produce finished garments.

For apparel and textile companies to adequately meet their legal obligations under the UFLPA, they will have to ascertain that none of the cotton that goes into the garment production of their extensive, and very often highly complex, factory supply chain is sourced from Xinjiang. The same is true for the solar industry – and given that Xinjiang accounts for an estimated 35 to 40% of the global silicon trade, this will be no easy feat.

China won’t budge on Xinjiang

The UFLPA will do little to change Beijing’s repressive stance towards Xinjiang. The replacement of Chen Quanguo, considered the chief architect of the Communist Party’s system of oppression in Xinjiang, is likely an indication of the next phase of control planned for the region, and not a pivot from its current position. As US-China tensions continue to escalate, companies will have little choice but to perform a delicate balancing act. On one hand, they are bound to US and other international regulatory and legal requirements, but in doing so risk a fragile presence in China where they are likely to receive hostile treatment from both the government and consumers. As has been the case in recent months, we expect that more companies are likely to be caught in the crosshairs.

Is this the end for Xinjiang sourcing?

The UFLPA is certainly the most sweeping measure to date taken against Xinjiang. The complex nature of global supply chains will make it immensely difficult for affected companies to confidently guarantee that they are in no way, shape or form sourcing from the region. Their compliance pathway must extend beyond ensuring that their Tier 1 suppliers are not located in Xinjiang. The ability to fully map out supply chains to include the suppliers of intermediaries, is key to having a more accurate picture of a company’s exposure to forced labour in Xinjiang. Without this, Xinjiang products – namely cotton, agricultural commodities and polysilicon – will continue to find their way into international supply chains, meaning companies may continue to inadvertently profit from Uyghur forced labour.