US named as ‘high risk’ country in new Civil Unrest Index - protests jump 186%

by Jimena Blanco and Karla Schiaffino and Victoria Gama and Christian Wagner,

The wave of unrest triggered by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis has been surprising in its scale, but not wholly unexpected, while the heavy-handed police response has rocked international perceptions of the world’s largest economy as a bastion of stability. The fact that racial tensions brought many US cities to a standstill is in no way unprecedented. Of the 10 largest episodes of violence since the 1967 Urban Riots, only one – the 1997 NYC blackout – was not sparked by tensions between racial or socio-economic minorities and the police. Given the backdrop of COVID-19, surging unemployment, a shaky economy and a divisive

election, the timing could not be worse.

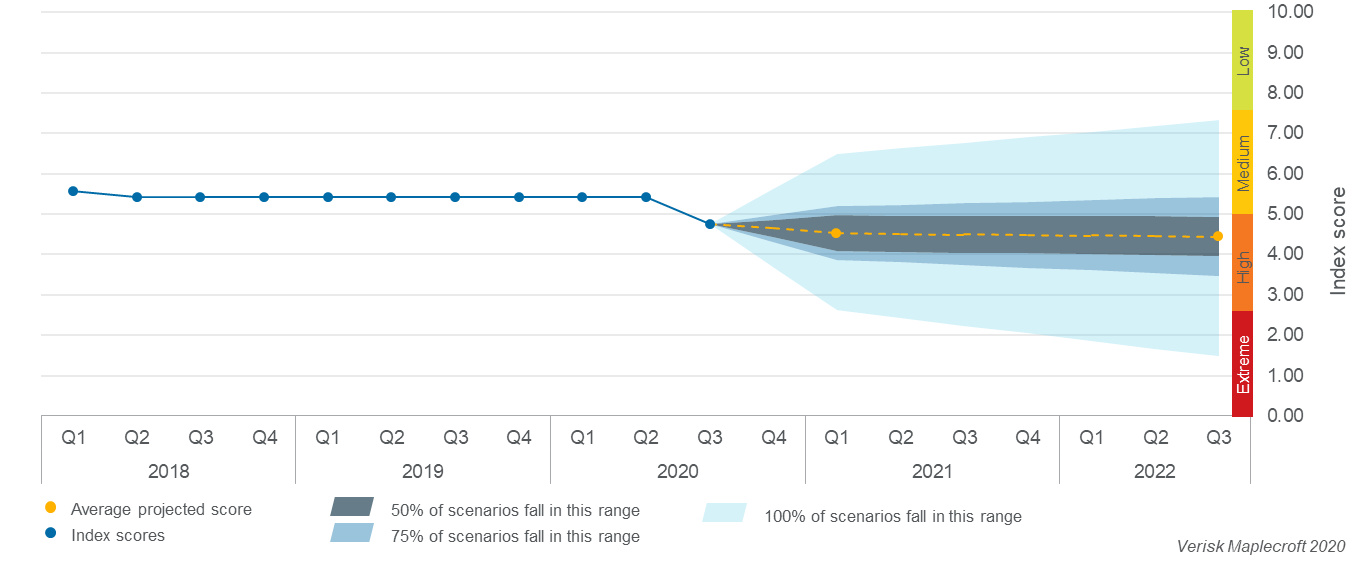

The events of the last days have seen the US drop into the ‘high risk’ category of our Civil Unrest Index for the second time. The first occasion since President Trump’s election triggered a series of protests in 2017. The quarterly index shows a fall of 13 places in the ranking to 78th highest risk out of the 198 countries measured.

Civil unrest incident data by GDELT shows a total of 9849 events nationwide in May – a 186% month-to-month rise from April. At the state level, Minnesota saw a 1486% rise in unrest, followed by Georgia (396%), Michigan (328%), and Kentucky (300%).

Learn more about Human rights due diligence

Tensions will remain high in run-up to elections

The ongoing protests reveal the high degree of political polarisation, particularly around social issues like race and gender discrimination, and structural socio-economic inequalities that have become evident once more under the Trump administration. As the indicators of our show, the marginalisation of racial and religious minorities is the biggest factor driving unrest in the US because of the profound impact on the living standards of entire communities, meaning that direct acts of violence to express discontent appeal to a broad range of community members.

Discontent over the Trump administration’s failure to tackle systemic marginalisation has inflamed social tensions since he took office. With critics arguing that the President’s actions equate to tacit support for extreme right-wing groups, the risk of disruptive social unrest will remain a constant threat as the November presidential election nears.

Our Civil Unrest Index projection, made prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent protests, forecast a 65.2% probability of unrest in the US worsening by 2020-Q4. Our latest projection maintains this trajectory, with a 64.9% likelihood that the US score in the Civil Unrest Index will continue to worsen by 2021-Q1 (see below).

Our latest projection is based on the deterioration of the mechanisms to channel discontent (such as freedom of speech and expression), and the reduced impartiality of law enforcement and the judicial system when dealing with racial minorities.

Despite growing civil society concern over the excessive use of force against African Americans, government efforts, including those of the administration of former President Barack Obama, have failed to eradicate the impunity with which the police act or address the lack of accountability for its actions. For instance, Officer Derek Chauvin, charged with the murder of Floyd, had 18 prior complaints made against him.

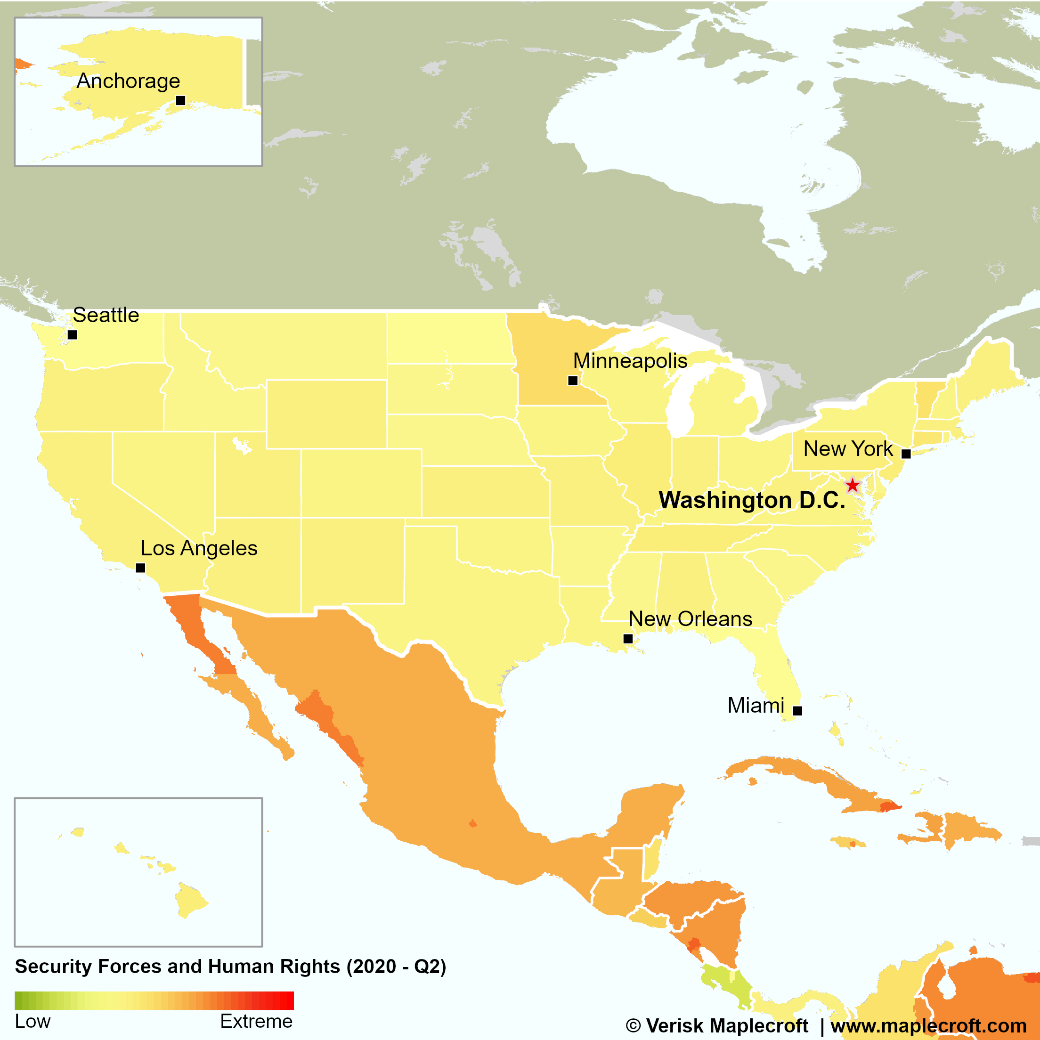

Moreover, Minnesota is identified as the highest-risk state in the US in our new subnational Security Forces and Human Rights Index, which assesses the risk of violations committed by officers of the law or the military (see map below). The data for this assessment was compiled prior to the killing of George Floyd.

The wave of unrest is driving political instability. President Trump’s threat to deploy the military will likely inflame protestors and sustain demonstrations in the coming weeks. The Democratic presumptive candidate, Joe Biden, will increasingly side with protesters, with African Americans being a crucial constituency for his presidential bid.

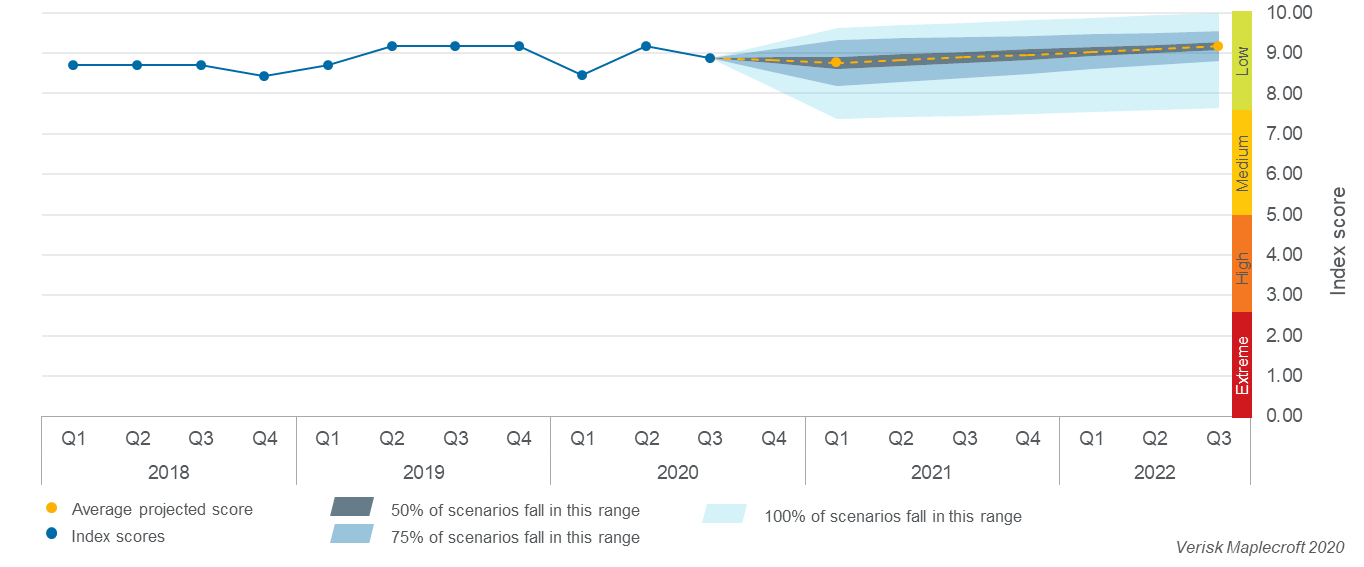

While President Trump is unlikely to face major internal challenges from his party this year, the protests will limit his ability to implement policy. This is the main driver of government instability – defined as the executive’s ability to implement its policy priorities – with a 43.2% probability of an increase in risk in by 2021-Q1 (see below).

Protests complicate US recovery from impacts of COVID-19

According to data by our sister company AIR, the number of COVID-19 cases will continue to rise in central and southern states over the coming weeks – precisely the jurisdictions experiencing some of the most intense protests. The breaking of social distancing in many urban areas will risk an increase in contagion rates. A second wave of contagion would add further strain on the already pandemic-hit economy, which official data shows has left more than half of black adults unemployed.

In our Recovery Capacity Index, which measures the ability of a country to bounce back from the pandemic, the US performs well, ranking 111 out of 198 countries. However, the increase in civil unrest will likely delay the US’ recovery from the pandemic.

High level of mistrust in the authorities will continue to hamper compliance with social distancing measures beyond the recent protests. The deployment of the National Guard in 21 states will risk having a counterproductive effect with militarisation set to create more pockets of violence as protesters and security forces clash.

Military deployments will also exacerbate the public perception that the government is seeking to restrict freedom of expression for opposition groups. By tightening penalties for protestors who demonstrate near critical infrastructure, the executive effectively has greater power to limit dissent. Temporary curfews and declarations of states of emergency, alongside legislative action and the President’s direct confrontation with social media outlets are set to play a role in the 2020 campaign.

The risk that the economic and social drivers of unrest once again collide with structural racial inequality will remain ever present. Therefore, we cannot rule out such episodes becoming more frequent in the volatile social, economic and political context that will dominate the 2020 election.