Ukraine conflict driving EU’s quest for strategic autonomy on critical minerals

by Capucine May,

The COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war have underscored two difficult truths about global trade. The former demonstrated that highly concentrated supply chains lack resilience, while the latter showed that dependence on strategic rivals for key resources is a vulnerability.

These are facts known all too well to the EU, which has had to limit its response to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine because of its dependency on Russian oil and gas. As the bloc looks to wean itself off Moscow’s fuel supplies, EU leaders are under pressure not to replace one vulnerability with another by turning to strategic rivals for critical raw material (CRM) imports.

The EU’s CRM strategy looks to get around this by boosting domestic production and processing efforts while partnering with friendly, like-minded countries when sourcing the materials needed for the green transition.

But obtaining strategic autonomy is no easy task. Critical mineral production and processing remains concentrated in a handful of countries – including autocratic, illiberal regimes.

Our analysis makes clear that the EU faces a number of downside risks during its transition away from CRM resource dependency, including backlash from environmental activists, high labour costs in friendly markets and the potential for retaliatory isolation from foreign markets.

EU dependent on strategic rivals for CRM imports

CRMs are the materials the EU sees as vital to its industry and the production of the goods and applications used in everyday life – including the ‘clean’ technologies that are key to the bloc’s transition to a low carbon economy.

The EU’s 2020 Critical Raw Materials list (*new since 2017)

| Antimony | Hafnium | Phosphorus |

| Baryte | Heavy Rare Earth Elements | Scandium |

| Beryllium | Light Rare Earth Elements | Silicon metal |

| Bismuth | Indium | Tantalum |

| Borate | Magnesium | Tungsten |

| Cobalt | Natural graphite | Vanadium |

| Coking coal | Natural rubber | Bauxite* |

| Fluorspar | Niobium | Lithium* |

| Gallium | Platinum Group Metals | Titanium* |

| Germanium | Phosphate rock | Strontium* |

Source: European Commission

These are identified by assessing a material’s economic importance – based on end-uses and industrial application – and supply risk – based on the concentration of global production and the governance profiles of source countries.

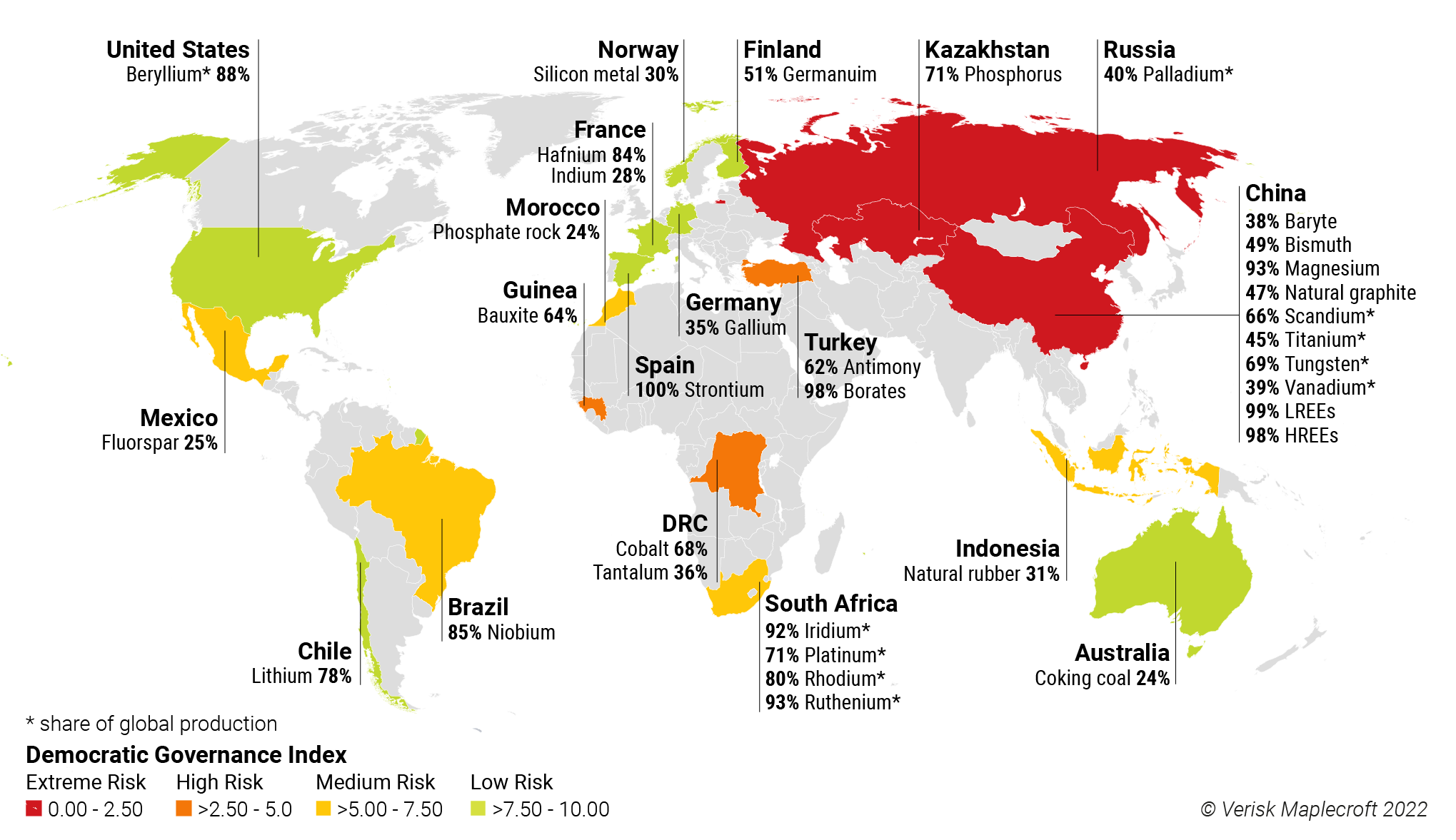

Currently, CRM production and processing is concentrated in just a few countries, including strategic rivals of the EU such as Russia and China. As a result, the EU imports a range of CRMs from countries with authoritarian or illiberal political regimes (see map below).

Indeed, 98% of the EU’s supply of rare earth elements comes from China. Turkey provides 98% of EU’s borate supply, Kazakhstan 71% of its phosphorous, and Russia 40% of its palladium.

But the Russia-Ukraine war has highlighted the folly of becoming economically dependent on regimes with poor democratic governance practices - adding urgency to the EU’s quest for an autonomous, sustainable supply of CRMs.

Strategic autonomy carries downside risks

The EU has adopted a multifaceted approach to critical material sourcing as it looks to avoid the pitfalls of resource dependency.

The bloc’s Critical Material Strategy is based on four pillars: increasing intra-European mining efforts, developing domestic downstream CRM processing facilities and renewable energy infrastructure, enhancing CRM recycling, and bolstering the geopolitical reliability of the supply chain by partnering with friendly states such as Canada, Australia, and Chile, as well as EU candidate countries in the Western Balkans.

However, downside risks remain. In the context of the Russia-Ukraine war, which is accelerating Moscow’s “Pivot to the East”, trade will increasingly face geopolitical hurdles. Mining companies that are perceived to be associated with the EU through funding and grant programmes risk getting shut out of foreign markets that deem the West to be a strategic rival.

While the EU’s emphasis on domestic sourcing presents opportunities for the mining sector, environmental activists are likely to oppose any efforts to boost mining operations within Europe.

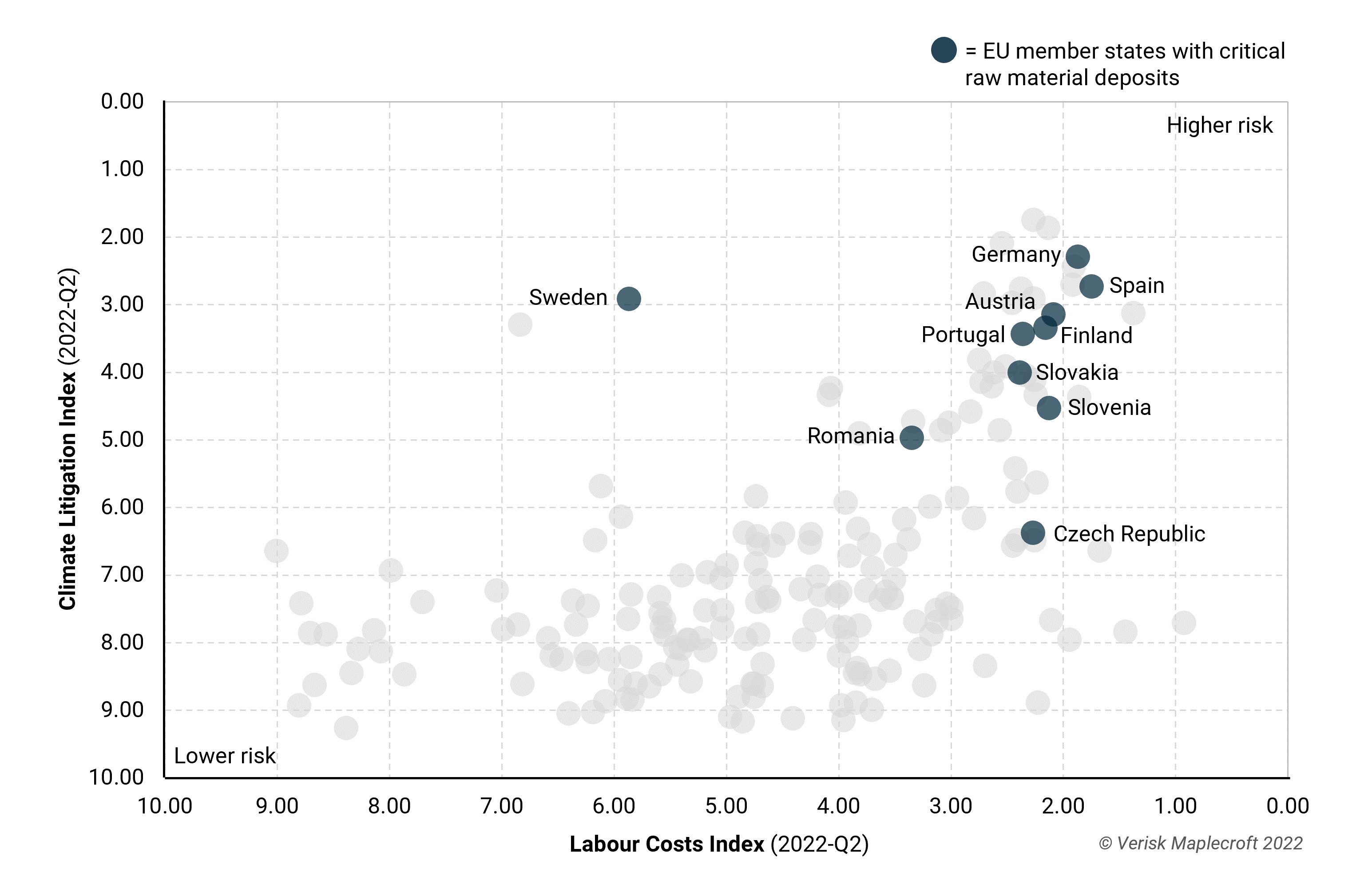

Our Climate Litigation Index takes into account the level of climate change awareness and activism in a country and can therefore serve as a proxy for this trend. The chart below highlights the extent of environmental activism within member states with untapped reserves of critical minerals – adding to the pre-existing burden of high labour costs.

Indeed, the largest lithium project in Europe, the Jadar project in Serbia, was cancelled in January 2022 due to mass environmental protests and concern from President Aleksandar Vučić that the issue may hamper his re-election bid. In Portugal, Germany, Sweden and Spain, lithium projects have all experienced delays or failed to get mining permits due to community opposition, mostly driven by environmental concerns.

These concerns have prompted a newfound determination to strengthen critical material supply chains with friendly states further afield. This has been a motivating factor in the push for an updated free trade deal with Chile, a key source of lithium.

But Chile’s constitutional reform process – during which it has mooted the nationalisation of mining assets – is a major source of uncertainty. What is more, the EU would still need to build the necessary downstream capacity to avoid sending lithium to China for processing.

A clean transition

As the EU looks for new sources of the raw materials needed for the green transition, it must ensure it doesn’t repeat old mistakes by becoming over-dependent on a handful of source countries.

At the same time, social dialogue will be of central importance if the idea of domestic CRM mining is to be sold to Europe’s ESG-conscious citizens. Strategic partnerships with aligned states like Canada, Australia and Norway will be vital, as will ESG-oriented bilateral development projects in developing countries.

These changes won’t happen overnight, but with an ongoing climate emergency and war on the EU’s doorstep, the incentives have never been greater.