The Americas in 2022 – Trends to watch

by Jimena Blanco and Mariano Machado and Victoria Gama and Will Nichols and Karla Schiaffino and Arantza Alonso,

As we close the door on a turbulent 2021, the outlook for the Americas will stay firmly on-trend. With inflationary pressures decidedly back, sustained growth and recovery to pre-pandemic economic levels is increasingly a pipe dream for many regional economies. Feelings are raw, both in response to the poor handling of the crisis by most governments and the unrelenting economic impact.

Against this background, major democracies like the US, Brazil, and Colombia will head to the polls in 2022. The risk of voter backlash against incumbents, and political elites more broadly, is almost certain in some crucial races. And far from the quintessential 'right-left' swing of the pendulum, the region is experiencing the 'surprise' victory of fringe candidates - from both ends of the political spectrum.

On the environmental and social fronts, we expect stakeholder activism to continue growing in the coming year. Yes, direct action against specific projects will continue across the region, but stakeholders will increasingly take institutional routes, and not only through the judiciary. As investors place hefty focus on the 'E' and 'S' in ESG, we expect stakeholders to demand a broader definition of 'community' and for minority groups to keep pushing for participation through more formal executive and legislative channels.

1) Stagflation threatens recovery

Despite rapid and well-targeted counter-cyclical policy action in response to the pandemic, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) remains the hardest-hit region globally. Overall positive growth this year will not be enough to return GDP per capita to pre‑crisis levels before 2023.

Furthermore, much of the rebound is attributable to the erroneously termed 'post-COVID reopening' – the truth is the pandemic is far from over, meaning this impetus is unlikely to hold as successive contagion waves and novel strains deliver new shocks in 2022.

And inflation may prove the proverbial straw that breaks the camel's back. The one thing all economies have in common: fuel and food prices are digging into households' buying power. US inflation hit a three-decade high, while Mexico shows the highest rate since 2001. In Brazil, double-digit inflation is eroding recovery prospects, and Argentina's staggering 52.1% continues to set records.

The steady increase in core inflation (especially in North America and Brazil) drives our concerns about the region transitioning towards a new inflationary regime, with diminished ability of central banks to whip deviations back into line.

In LAC, the large informal economy means the monetary and financial tools that central banks typically use to contain inflation are less effective than in APAC or developed economies. And the hardest-hit social sectors will be those devoting the largest share of income to price-volatile staples, just when governments are phasing out pandemic emergency aid.

2) Largest democracies hit (by?) the polls

Three of the western hemisphere's largest democracies will hold national elections in 2022. And in all, we expect incumbents to suffer voter backlash, including the almost certain and unprecedented rise of the left to power in Colombia, and its potential return in Brazil. In the US, Biden's climate agenda will be hostage to the electoral outcome.

Despite a better-than-expected economic recovery, President Iván Duque's Centro Democrático (CD) is losing ground ahead of Colombia's legislative and presidential ballots (in March and May, respectively). Left-winger Gustavo Petro is increasing his lead over the CD's Zuluaga, and the political centre remains packed, unable to unify behind a single candidate. Therefore, the left taking the Palace of Nariño has never looked more likely.

Brazilians will decide in October if Jair Bolsonaro becomes the first one-term president in three decades. Polls show his popularity sinking (at 22% approval in early December), with two-time former president Lula Da Silva consolidating his position as the strongest challenger. The political system is going into full electoral mode, but the gap between candidates and voters is widening, making voter backlash against the political elites a major risk for any forecast.

In November, the US will renew 39 governorships, a third of the Senate, and all House seats. Rising inflation and political polarisation have dragged President Joseph Biden's approval in December 2021 to its lowest point (42%) since taking office. If Republicans regain control of Congress, Biden will see his efforts to confront the climate crisis, advance social policies, and combat COVID thwarted.

3) Transformation paths: turbulence ahead?

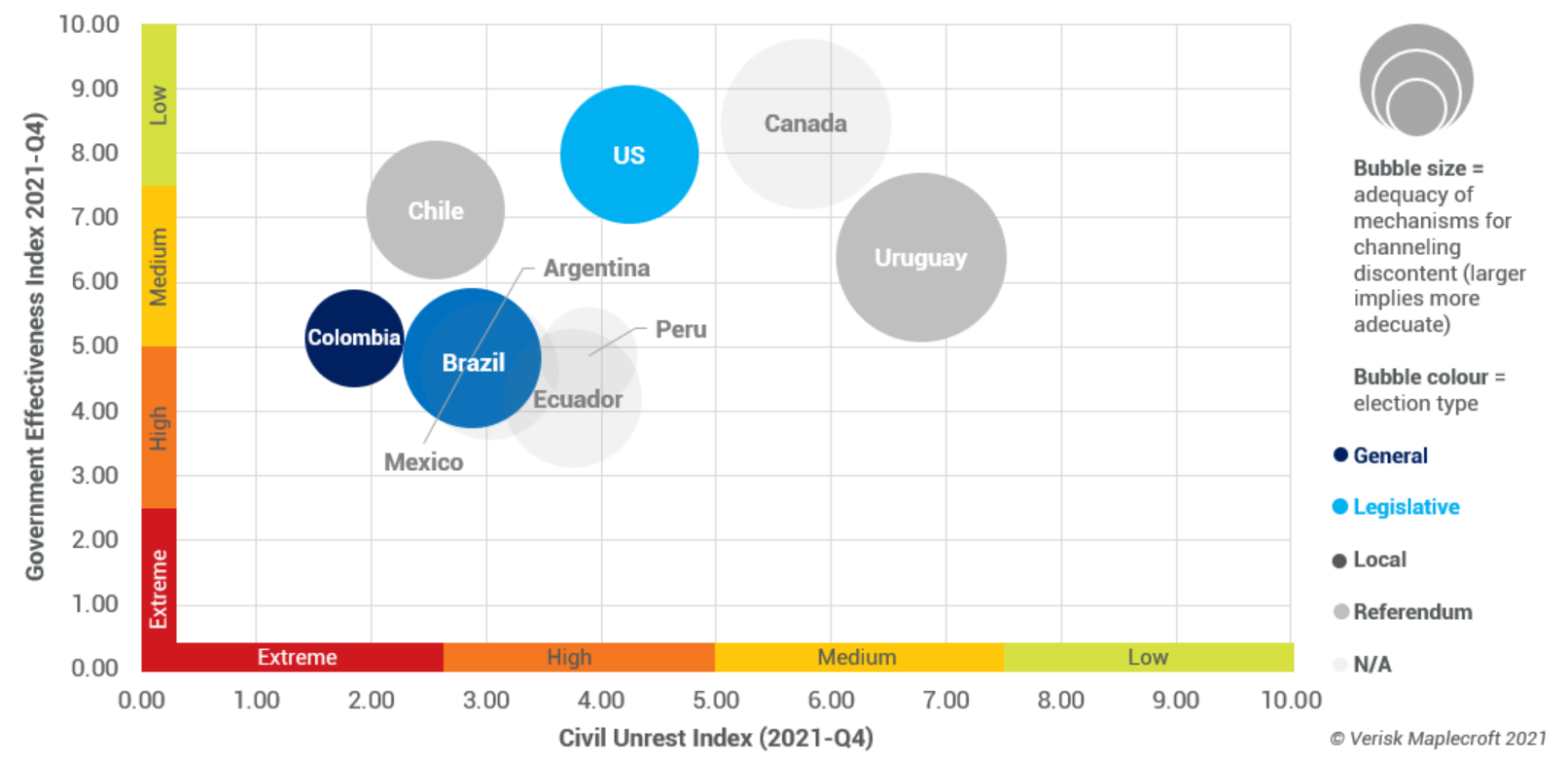

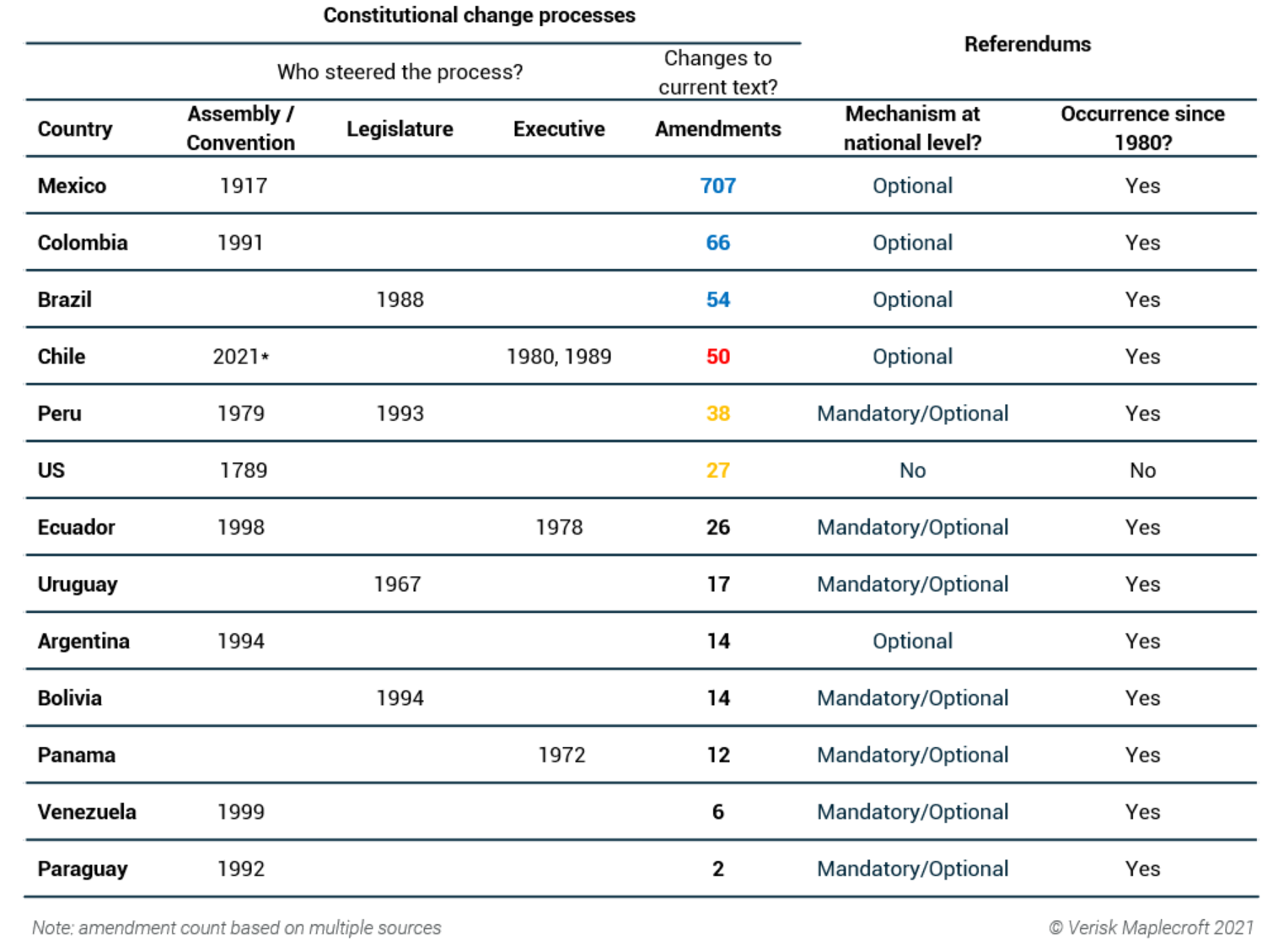

With growth under siege, a key variable for the future of regional democracies is whether traditional participatory mechanisms can provide an effective tool to channel dissatisfaction.

Democratic backsliding is already taking place – and the rise of new autocratic or authoritarian regimes can no longer be dismissed. Data by Latinobarómetro shows that a majority (51%) of Latin Americans would not object to a non-democratic government if it solved their problems. The figure is the highest in two decades, with satisfaction with democracy plummeting to the lowest level (25%) since 1995.

Exiting 'civic stagnation' is never easy, and Chile provides the region with an example of how piecemeal reform (see below) failed to appease voters, leaving institutional overhaul as a release valve of last resort. But this is a double-edged sword, the effectiveness of which will not be known for years to come.

The constitution will dominate Chile's political debate until the exit referendum in late 2022-Q3, inspiring other countries already experiencing major episodes of civil unrest. But if a new constitution were rejected, the country would run out of alternatives, exposing the apparent obsolescence of participatory mechanisms and increasing the risk of renewed turbulence as the path for change.

4) Demands for environmental justice will grow (louder)

Across the continent, building pressure on natural habitats paired with growing environmental awareness drives a movement dedicated to ensuring communities actively benefit from the extractive projects they host.

Widespread constitutional rights for a clean environment provide the legal basis for recourse against damaging projects. Companies must explain how projects deliver these benefits as part of permitting processes - or face rejections and potential legal challenges at all stages of operation.

Communities will increasingly demand that operators broaden definitions of affected communities and expand engagement to those. Doing so will help companies across industries to meet growing concerns from regulators and investors.

5) Indigenous peoples will cash political capital to drive self-determination

Among the stakeholders taking on investors through a variety of strategies, indigenous communities have elbowed their way to the negotiating table and are pushing for direct participation in decision-making.

Hence, a full range of advocacy strategies, ranging from direct action – protests, roadblocks, riots – to more institutionalised alternatives – extraterritorial litigation, demands for robust FPIC legislation, and reserved seats in legislative bodies – will be deployed against projects impinging on land rights.

Companies, suppliers, buyers and investors need to gain the trust of indigenous communities who have been historically affected by the development of economic activities. They will only be able to operate if they implement a culturally appropriate rights-based approach, grounded on communities' right to self-government.

Plebiscitary populism, a risky slippery slope for democracy

Sustaining economic growth will be the dominant concern for the Americas in 2022. A re-launched demand for prosperity will impact policy choices across the hemisphere and shape electoral results in some of the largest democracies. And the stakes are high: if democratic institutions cannot meet popular demands, regional voters seem more open than ever to trying non-democratic alternatives.

This backsliding would have many shades of grey before a break in the democratic order. Fueled by popular demands of direct participation, a new regional wave of 'plebiscitary' leadership could take hold in jurisdictions with high levels of dissatisfaction. Similarly, with once-fringe political actors slowly making their way to decision-making positions, straightforward attempts for institutional engineering cannot be ruled out.