How can I tap the sovereign green bond opportunity?

Key take-aways:

- Countries are turning to sovereign green bonds to finance climate-friendly investments

- Opportunities for energy-related green bonds are concentrated in OECD countries

- Emerging markets represent an opportunity for green bonds linked to adaptation

The cost of climate change adaptation is simply too hefty for many of the most vulnerable countries

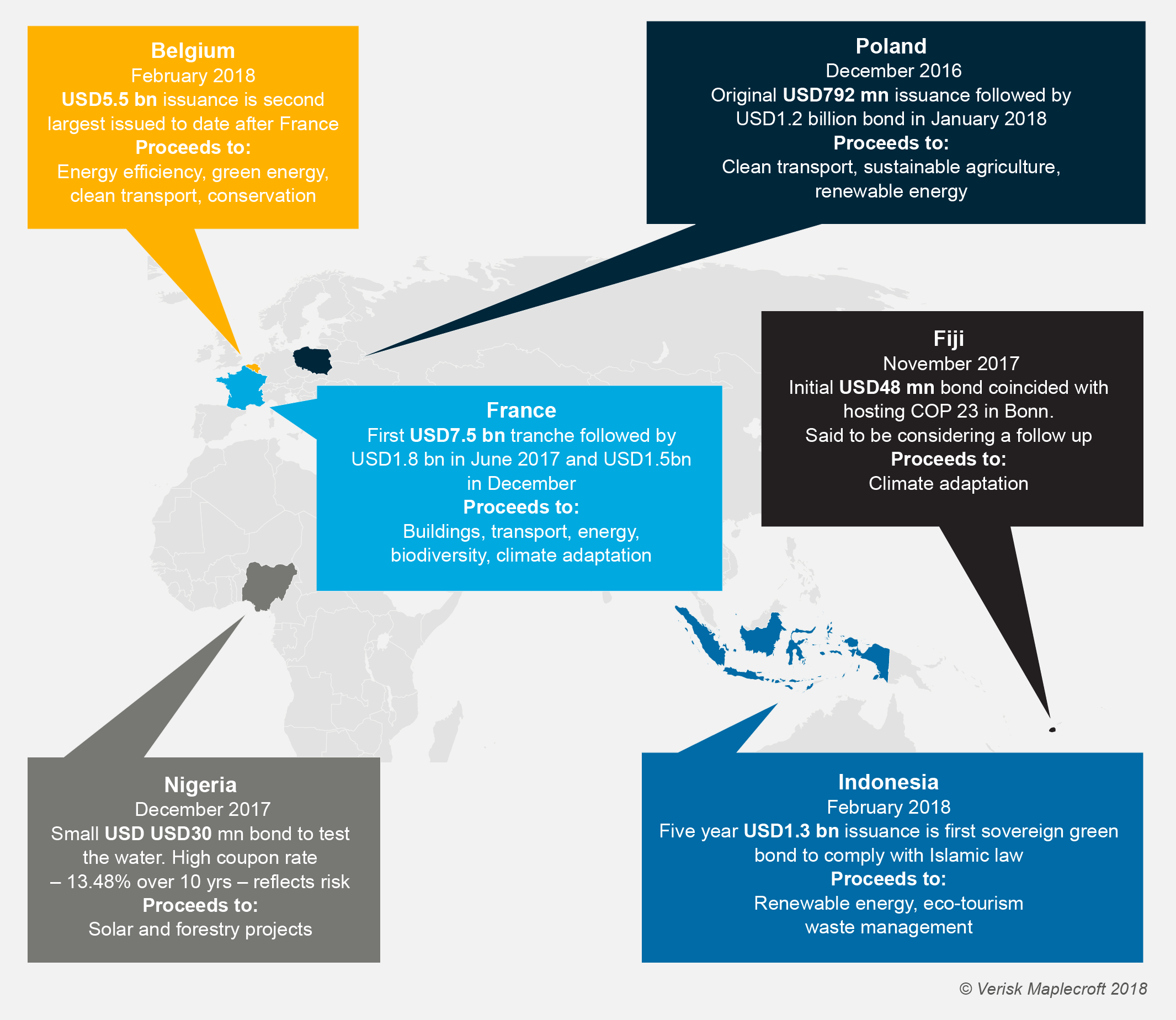

With levels of international commitment to climate funds appearing increasingly inadequate, nations are looking for new sources of funding. In the past 18 months, six nations have issued sovereign green bonds, raising a combined USD19.5 billion to finance clean energy projects, climate resilient infrastructure and other sustainability programmes. This is a small slice of an overall green bond market worth USD160.8 billion in 2017; but if current trends continue we expect many more sovereign issuances in the coming years.

Green bonds - A new market

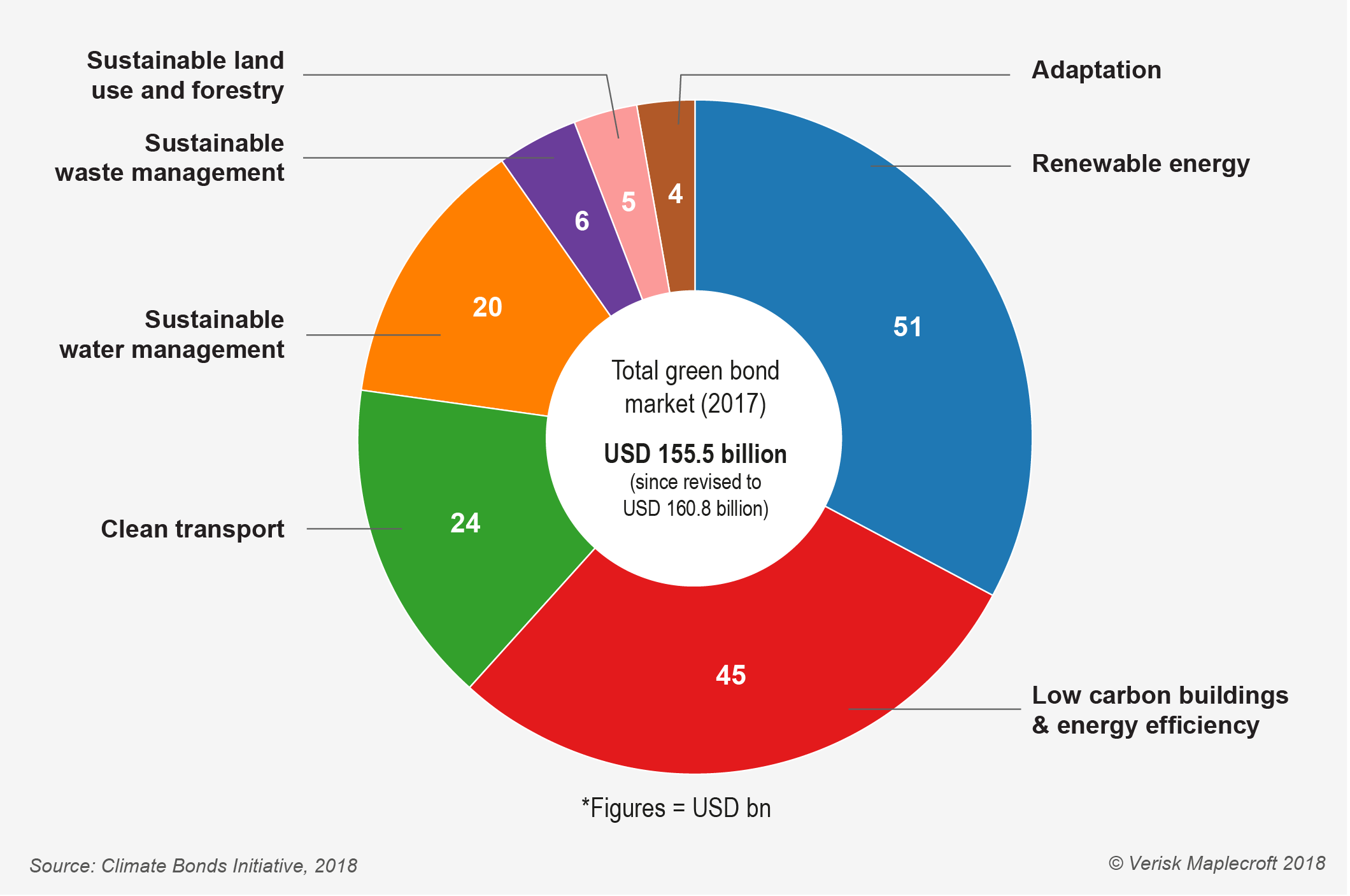

Green bonds vary little from traditional bonds except that the issuer channels the proceeds towards climate adaptation and mitigation projects. The market only began in earnest in 2007 and is still dominated by development banks, corporates and municipalities.

There is no consensus that green bonds enjoy a systematic pricing premium over vanilla bonds, government or otherwise, but we’ve seen green issuances attract a much wider spread of investors, which pushes down borrowing costs. For example, 61% of investors in Poland’s green bond had never invested in any of the country’s standard sovereign bonds.

Poland kicked off the sovereign green bond market in 2016 and five other countries followed, with France’s USD10.7 billion issuance last year marking the biggest to date (see figure below). Proceeds largely targeted green energy projects and climate change resilience initiatives, with some opting to address issues such as cleaner transport or afforestation.

The green bond opportunity

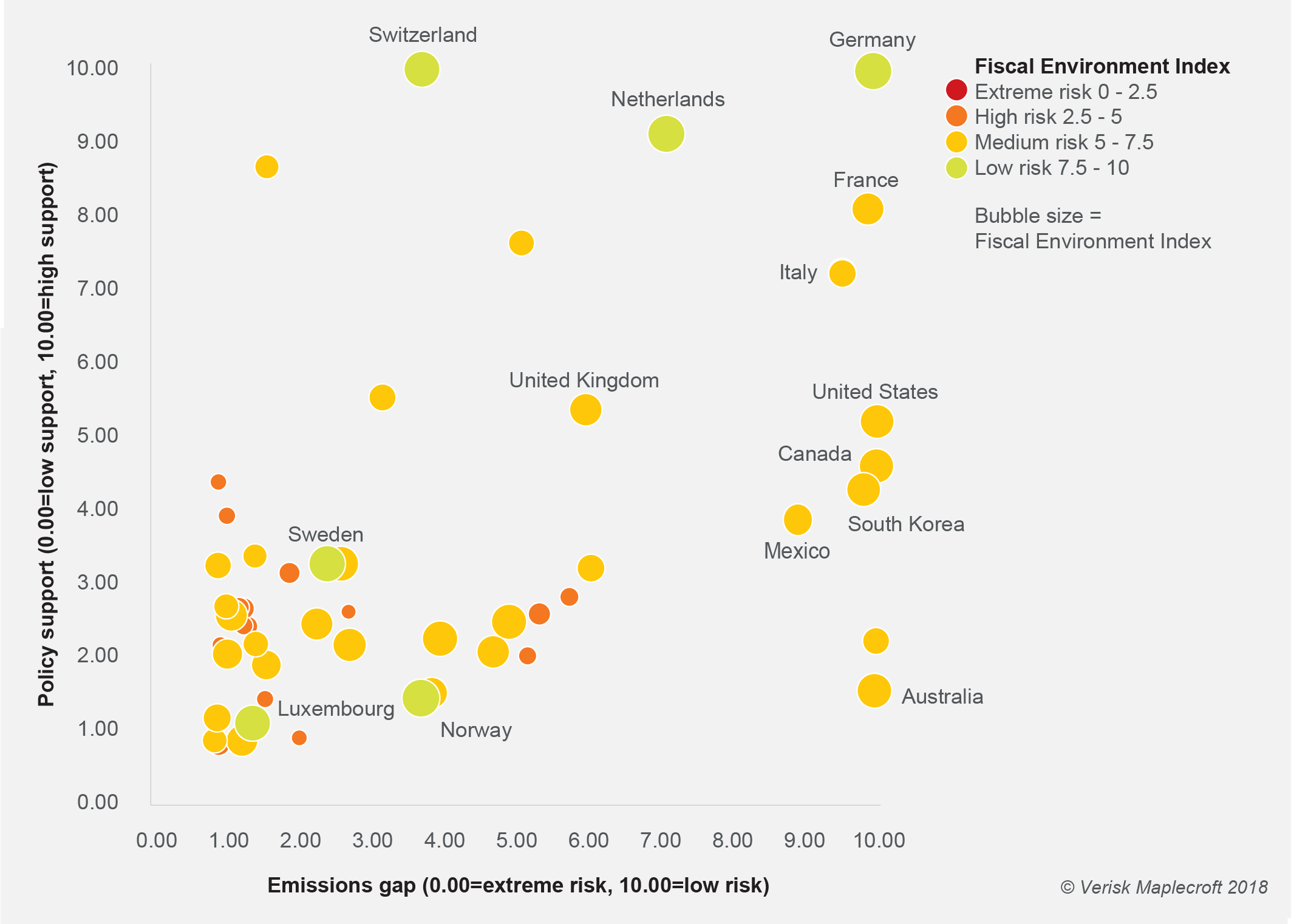

To gauge which countries might be next to issue a green bond, we identified nations that have both the need and the capacity to make climate-related investments. In the figure below, we’ve focused on sizing the need for renewable energy investment – the largest recipient of green bond investments to date. Using data from our Carbon Policy Index , countries are plotted based on with emissions gap – the difference between their current emissions and stated goal under the Paris Agreement – and support for renewables through policy incentives. The bubble size represents the country’s score on our Fiscal Environment Index , which is a proxy for sovereign credit risk.

Clearly, OECD countries look best positioned to issue a sovereign green bond, notably Germany, Italy and France, which has a green bond under its belt already. The US and UK also appear to be good candidates on the graph, but neither are likely to issue a bond in the coming year.

The Trump administration has shown little appetite for emissions reductions and has moved to rescind the Clean Power Plan and exit the Paris Agreement. However, states and cities picked up the baton on climate action and, given the US is the biggest market for green bonds below state level, we expect to see more sub-national issuances here. The UK has a highly privatised energy sector, which raises the potential for corporate bonds, but could rule out a sovereign green bond.

Emerging markets are largely absent from the picture, partly because under the terms of the Paris Agreement many can increase their overall emissions, albeit to a level below business-as-usual projections. These countries will instead need to direct investments towards adapting their economies and infrastructure to a changing climate.

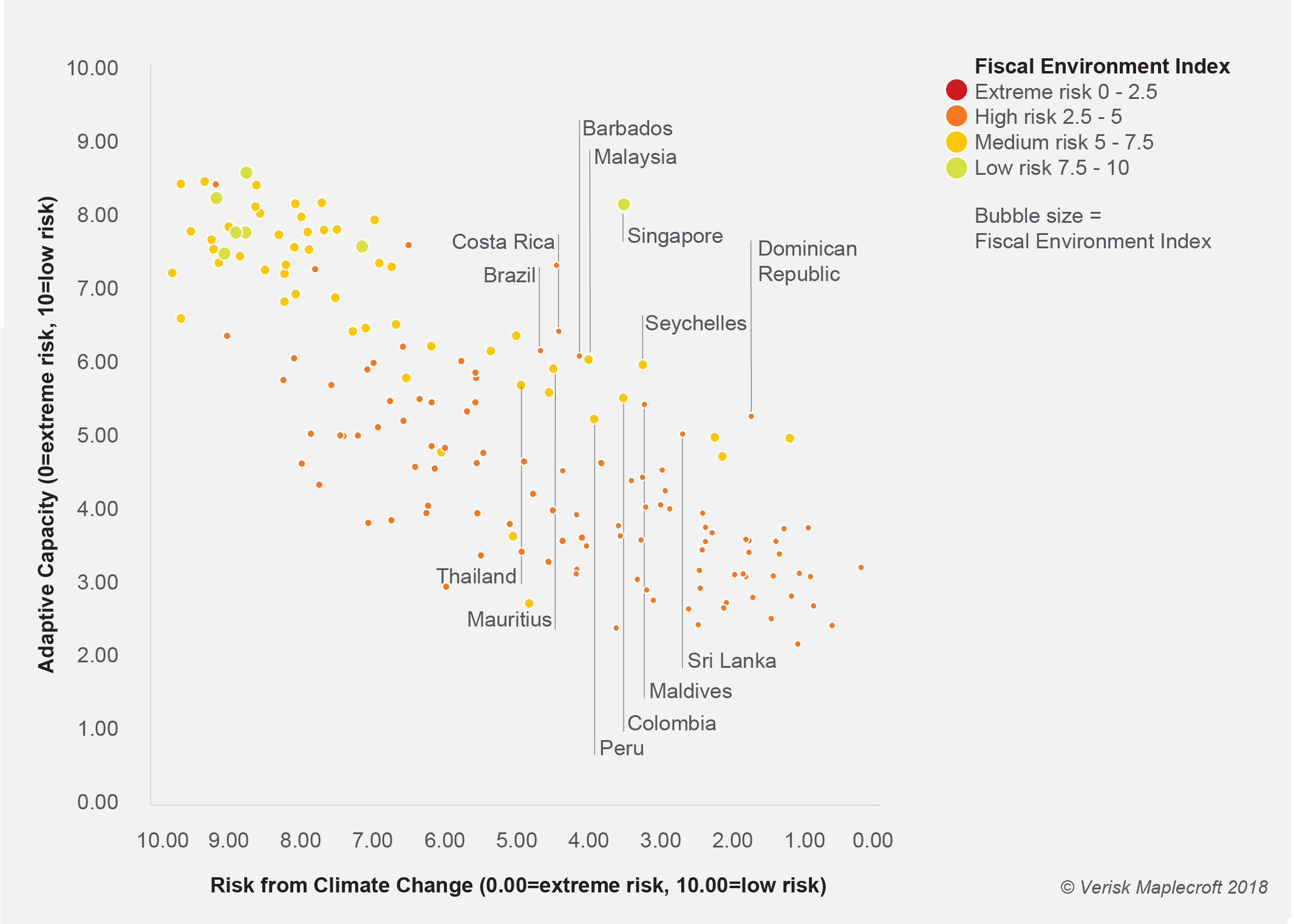

We’ve examined the need for investments in adaptation to climate-related impacts. This is a combination of our Climate Change Exposure and Climate Change Sensitivity risk indices to demonstrate need for resilience measures, plotted against the Climate Change Adaptive Capacity index (see Focus box below). Again, bubble size corresponds to our proxy for credit risk.

This tells a very different story, one where emerging markets offer the greatest opportunity for green financing. Singapore stands out as a country facing significant challenges from climate change, but able to tap financial markets relatively easily. Relatively wealthy economies like Colombia, Malaysia, Brazil, and Thailand lack Singapore’s stellar fiscal environment, but could reap the benefits of green bond financing if the oversubscription of issuances by the likes of Nigeria and Fiji is repeated.

Turning green bonds vanilla

We recognise sovereign bonds are likely to remain a small part of the wider green bonds universe, at least in the next few years. Political will, the division between public and private ownership, and the extent of government decentralisation will all impact whether a nation sees green bonds as part of its toolkit. Countries that find it difficult to borrow on international markets, a cohort that overlaps significantly with those nations most threatened by climate change, have other funding options, ranging from public revenues to international donations.

However, improved verification of issuances and wider application of the Green Bond Principles, voluntary guidelines created by a host of financial sector companies and stakeholders, will add transparency to an inconsistently regulated market. And should new issuances from Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Hong Kong and Sweden prove as attractive to a diverse investor base as sovereign green bonds to date, other nations may follow suit.

As much as USD1 trillion in annual green bond issuances will be needed by 2020 to meet the Paris Agreement goals for carbon mitigation and climate adaption. As the market looks to close the gap, this research gives investors the tools to identify the most promising opportunities.