Tackling climate change and modern slavery together

by Dr James Allan,

Pope Francis's call in 2015 for the world to tackle climate change and modern slavery simultaneously marked the first time a major international figure linked the two issues. Governments, businesses and civil society have taken action on both topics since then but largely in isolation.

Several governments for example - notably the UK and US - are ramping up their efforts to tackle exploitative working practices. In response, many multinational businesses are now taking steps to assess slavery risks in their operations and supply chains.

Yet eliminating modern slavery for good requires a concerted focus on the underlying causes. These causes vary across the globe but two of the most important drivers of exploitation intersect with widely recognised outcomes of climate change: forced migration and poverty.

Who is most vulnerable to both climate change and modern slavery?

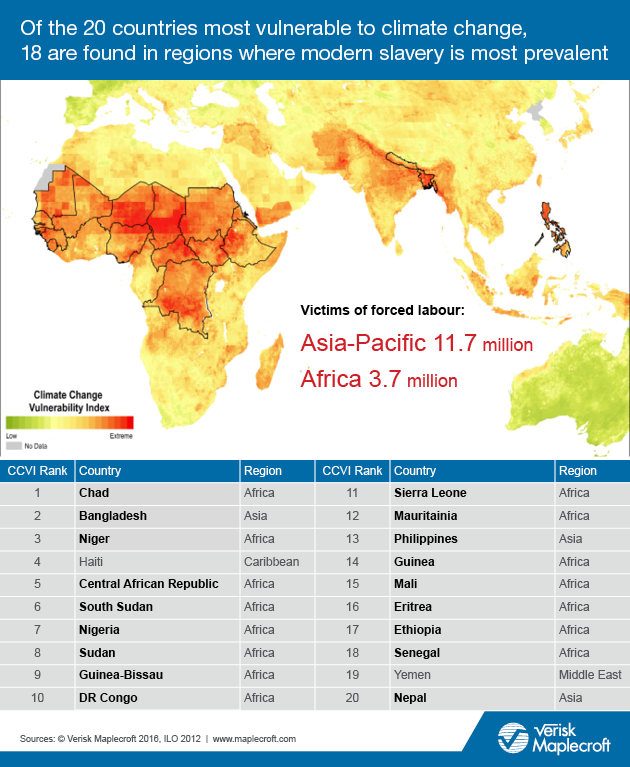

The Pope's clarion call came without specific geographic instructions. However, global environmental models and social survey results suggest there are millions of people at risk in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

According to our Climate Change Vulnerability Index 2016, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia account for 18 of the 20 countries most vulnerable to climate change. Of the almost 21 million people worldwide thought to be the victims of forced labour - one of the most common forms of modern slavery - the majority are in Asia-Pacific (11.7 million) and Africa (3.7 million)

In the Middle East, Kuwait witnessed what could be the highest ever recorded temperature on earth in July 2016 (54°C or 129.3°F), while the Levant region - Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria - is suffering from its worst drought in 900 years. International Labour Organisation statistics for the Middle East largely pre-date the ongoing Syrian conflict and associated migrant crisis, but still reveal three in every 1,000 people is a victim of forced labour.

Signals of future vulnerability

It is hard to predict how the prevalence and distribution of modern slavery will change over time. These patterns will be largely determined by the effectiveness of regulatory interventions, economic and social (in)stability, and a host of other political and social factors.

Although slavery affects all sectors, the food and beverage, agriculture and seafood, apparel, retail and ICT industries are among those most exposed to the risks of association with the practice.

For these industries, two key dynamics are worth paying close attention to.

First, extreme weather events can destroy everything people have in an instant. Left without a home, possessions or family, large groups of people can suddenly become vulnerable to slavery. Many of the Syrian migrants scattered across the Middle East and Europe are exposed to labour exploitation. The conflict which displaced these people has at least in part been linked to climate change.

The Asian countries of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar already contain disproportionately high numbers of people working in abusive conditions (including those trafficked to neighbouring countries), and are likely to experience some of the greatest effects of climate change. For example, a significant number of the slavery victims identified in Thailand's seafood industry are from Myanmar, a country repeatedly struck by natural hazards in recent years - including Cyclone Nargis in 2008, which killed 139,000 people and exposed countless others to international trafficking.

A second key area of concern is the fact that climate change increases poverty. This in turn increases the number people that are vulnerable to modern slavery.

According to the World Bank, there could be 100 million more people living in poverty by 2030 as a result of climate change. A major driver of this increase in poverty is the reduction in crop yields due to climate change and rising food prices, which can force people from their homes and into the arms of traffickers. And if food prices go up but wages don't, then risks of indebtedness grow. Africa and Asia lead the world in the proportion of people that are dependent on agriculture for their livelihoods, with over 40 per cent of workers employed in the sector.

What joined-up thinking looks like

Despite limited action to-date, social and regulatory forces are encouraging more joined-up approaches to tackle these interconnected challenges.

The new UN Sustainable Development Goals address poverty, climate change and modern slavery simultaneously. Governments, businesses and civil society around the world have committed to achieving these goals. We're also seeing companies integrating legal obligations from modern slavery laws into the same management systems and processes responsible for handling climate change.

Although clear best practices are yet to emerge, companies can address climate change and modern slavery simultaneously by:

- Creating strategy or policy frameworks through which joint action can be taken

- Integrating both issues into responsible or sustainable sourcing programmes

- Conducting capacity-building and awareness-raising activities, both internally and through collaboration with industry peers, suppliers or local partners

- Introducing CSR programmes and initiatives focused on at-risk groups

- Engaging with relevant industry and multi-stakeholder initiatives

No single company aims to resolve environmental or human rights challenges on its own. Tackling climate change and modern slavery in tandem will require a collective effort. After all, both issues are simply too important to leave to divine intervention.