Asia experienced one of the world’s first COVID-induced food protests when residents of Manila took to the streets on 1 April. Food insecurity has since played a role in protests across the region, including in India and Bangladesh. We expect that these initial protests are a sign of much bigger problems to come.

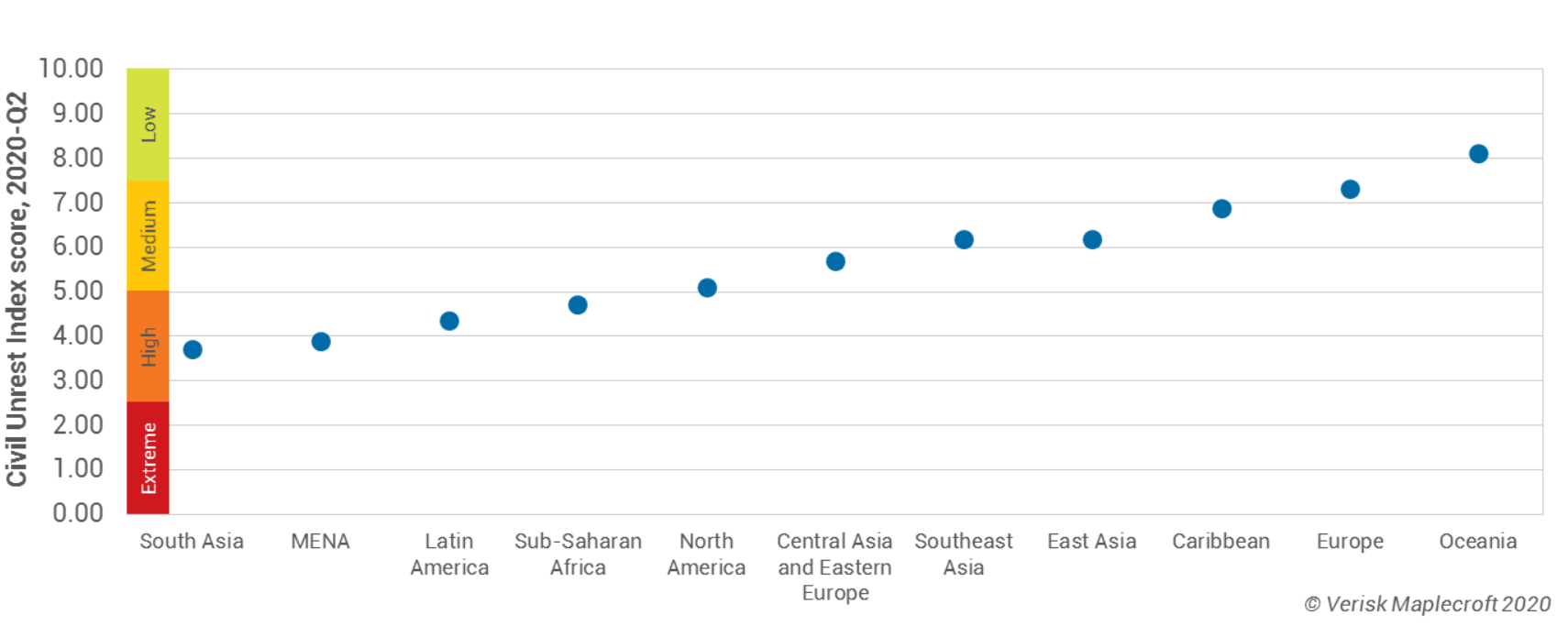

South Asia and, to a lesser extent, Southeast Asia are potential powder kegs of unrest amid a perfect storm of food shortages, higher prices, sweeping job losses and plummeting remittances. As the table below shows, South Asia is rated the highest risk region globally in our Civil Unrest Index in 2020-Q2, ahead of MENA and Latin America. This means companies and investors, already reeling from travel restrictions, lockdowns, a see-sawing stock market and oil price crash, face another headache that is unlikely to go away any time soon.

Ranks of hungry protesters to swell as economic fallout and job losses mount

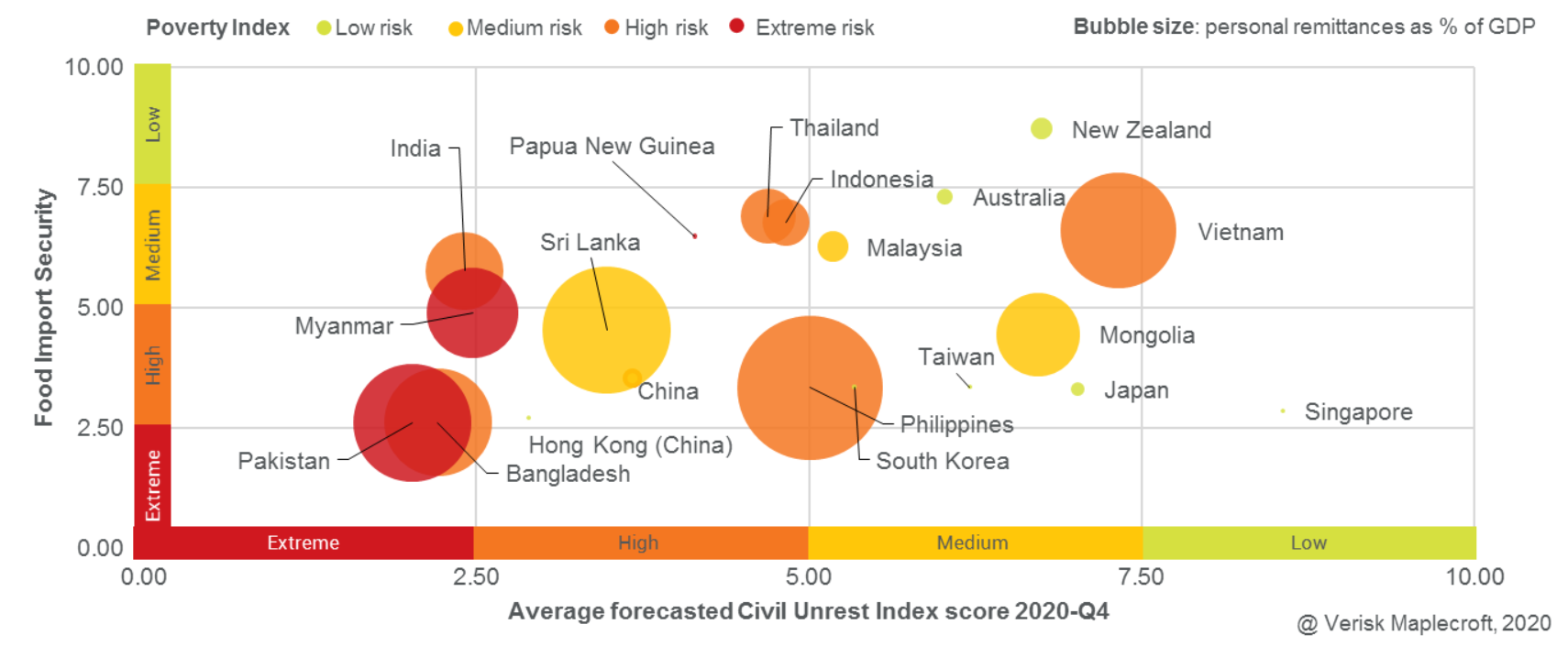

Not a single Asian country receives a low-risk rating on our Food Import Security Index, with most falling into the medium or high-risk categories. But while the risk of a surge in unrest is elevated across the region, it is most acute in three South Asian countries that already witnessed instability ahead of the pandemic.

Bangladesh, Pakistan and India are currently ranked the 10th, 13th and 19th highest risk countries globally in our Civil Unrest Index and already considered extreme risk. Alongside neighbouring Myanmar, we expect these countries to face large-scale spikes in protests that will likely see their position in the index slip even further.

As the figure below shows, all three states are also designated as extreme risk in our Civil Unrest Index projections for 2020-Q4 (located in the lower-left quadrant of the chart), as well as for poverty (red or orange bubble colour). Bangladesh and Pakistan also receive high-risk ratings in our Food Import Security Index, while India sits in the medium-risk category. Moreover, the countries are among the most dependent on remittances in APAC (denoted by bubble size). These are fast dwindling as overseas workers in the Middle East, Singapore and other developed economies lose jobs in hard-hit sectors such as construction and manufacturing.

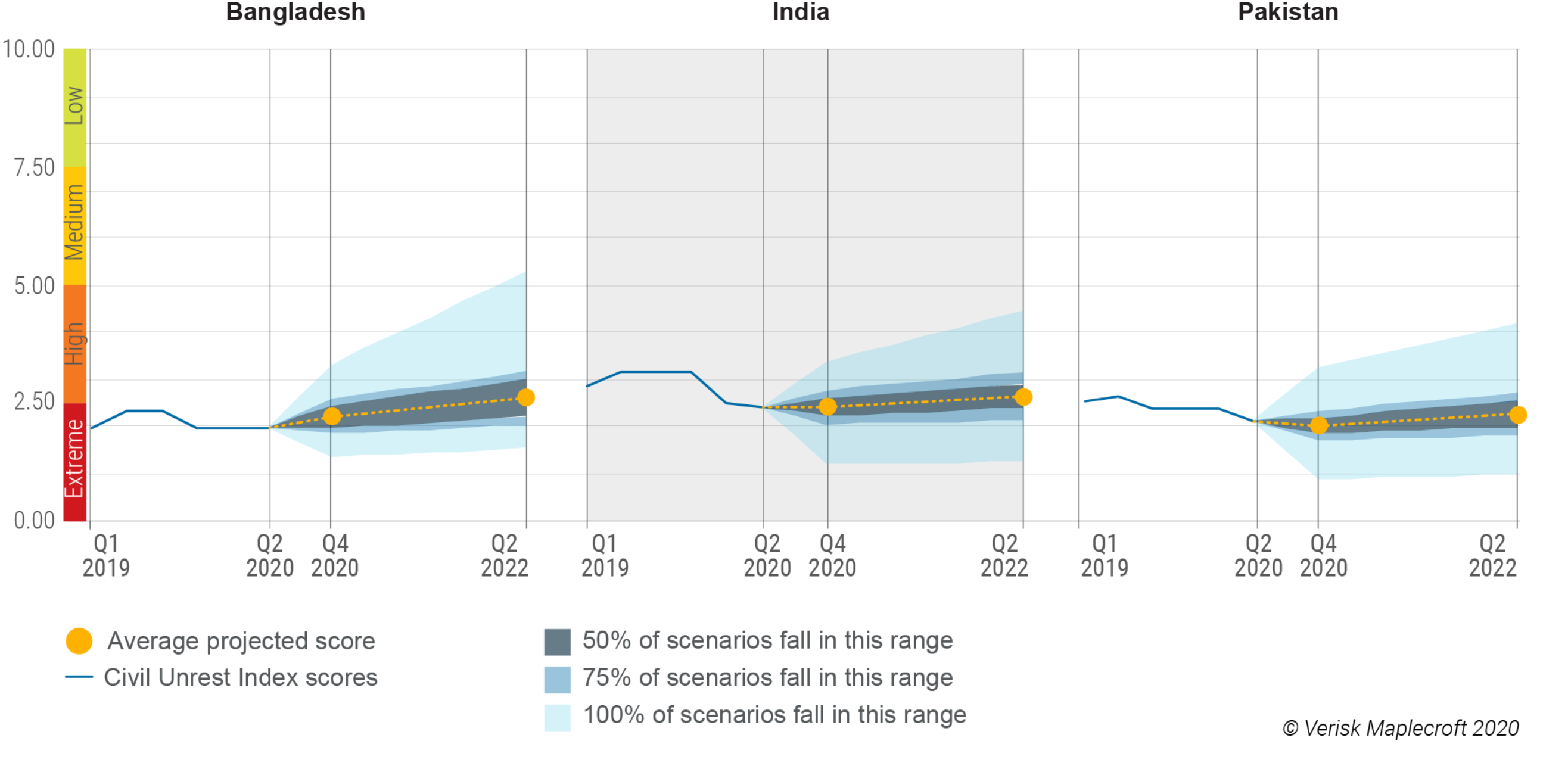

We expect all three states to remain in the extreme risk category over the next six months (see projection below). As the effect of the pandemic gradually fades, however we expect protests to wear off and the three countries to register moderate improvements by 2022-Q2.

India: End of lockdown will see return of unrest

India has accumulated a stockpile of essential staples ahead of the pandemic and out of the three countries is the least dependent on food imports. But a combination of lockdown-induced disruption and state inefficiency has already led to increased food insecurity, which is only set to deepen over the coming months as the economy sheds jobs at a rapid rate. Reports have also indicated that a number of Indians have also died from starvation during the outbreak.

As India looks to ease lockdown measures and resume economic activity, both the frequency and severity of protests are likely to increase in the coming weeks.

We expect a rapid resumption in protests over pre-existing issues – most significantly the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which saw hundreds of thousands of Indians take to the streets in the months before the pandemic.

As more people slide back into poverty, cases of protests related to food security are likely to increase and potentially blend with CAA-linked unrest, particularly in camps housing internally displaced migrant workers. This underpins our Civil Unrest Index projections for 2020-Q4, which see little improvement to India’s risk outlook and maintains the country’s extreme risk score until 2022-Q2.

Bangladesh: Garment workers hit the streets as their livelihoods evaporate

Bangladesh is currently ranked the 10th and 7th riskiest country in the world in our Civil Unrest and Food Import Security indices, respectively. Massive layoffs in the garment industry – the country’s main export sector – have come quickly amid falling global demand and supply chain disruption. These downsizings have deepened existing levels of food poverty, and will continue to fuel COVID-19 related unrest, particularly over the next six months. But we expect the hard-hit manufacturing sector to gradually get back to its feet by 2020-Q4, which will likely slightly moderate labour unrest as economic activity resumes.

Bangladesh also scores in the extreme risk category in our Security Forces and Human Rights Index. This indicates that the government will likely choose to suppress any civil unrest before it escalates to the point where it threatens domestic stability. The government’s heavy-handed response in turn makes it unlikely for localised labour unrest to persist for long bouts even amid persistent insecurity over food and employment.

Find out more in our new webcast: COVID-19 unravels labour rights in Asia’s garment sector

Register nowPakistan: Pandemic will amplify existing pressure on food supply

Pakistan is the 6th most food insecure country globally according to our data. Coronavirus-related disruption will be adding to existing pressure on food supplies, driven by factors ranging from the weakness of the rupee, to drought and historically large swarms of locusts.

Spiralling food prices have fuelled protests throughout Imran Khan’s premiership, and in February 2020 the government introduced subsidies to reduce the cost of staples.

We expect such efforts to be ineffective against a global supply crunch. Combined with rumbling disenchantment over the government’s handling of numerous other issues, we see only a remote possibility of Pakistan improving its performance in our Civil Unrest Index over the coming year. Pakistan is currently the 13th riskiest jurisdiction in the index.

Risk will remain elevated until the pandemic runs its course

Disruption in the food supply chain, rising food prices, skyrocketing job losses and dwindling remittances will create a potent recipe for instability. Compounding the problem is a likely return of protests around pre-existing grievances temporarily suppressed by the pandemic – such as around the new citizenship law in India. This means that companies and investors across the region will need to pay heed as unrest will continue to linger long after sources of more short-term disruption – such as lockdowns and travel restrictions – are lifted.