The COVID-19 pandemic has handed us a global lesson on the prudence of being prepared for a ‘grey rhino’ event – high impact incidents that are likely to happen but are commonly overlooked. But even with this first-hand experience, will this translate into proactivity on the other obvious global risk parallel: climate change?

Below, we examine seven ways COVID-19 has complicated the global climate agenda

1. COVID response relegates climate action

That the Madrid conference centre that hosted COP25 and the planned venue for COP26 in Glasgow are now both field hospitals on the front line of the battle against coronavirus is a stark manifestation of how the immediate threat has eclipsed a longer-term risk. In theory, postponing COP26 until 2021 gives states extra breathing room to enact the policies they pledged under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

But motivated parties and civil society will expect countries to arrive at the rescheduled summit ready to address key unresolved issues around finance, the rulebook for ratcheting up climate goals, and monitoring and reporting requirements. Yet governments now need to balance the cost of transition policies with the economic recovery from COVID-19, threatening forward progress on policy implementation.

2. Chance to rehash environmental standards

With so many impacted sectors asking for help, lawmakers will find arguments to deprioritise climate regulation over maintaining basic commercial viability are difficult to ignore. Already, the Trump administration has framed the situation to further its deregulatory agenda, softening enforcement of certain standards during the outbreak and rolling back Obama-era auto emission levels.

Similarly, European airlines are demanding delays to new environmental taxes designed to limit air travel emissions, citing the significant financial impacts the industry is experiencing as a result of restrictions on movement to combat the virus spread. Globally, the industry is also amend its carbon reduction scheme fearing that using 2020 as a base year for emissions will make targets much tougher to meet.

But such opportunism will elicit a strong reaction from campaigners and near-certain litigation.

3. Emissions reporting up in the air?

Air quality has already improved as the global shutdown dramatically reduces company activities. With a near inevitable concurrent reduction in GHG emissions, carbon reporting for this year is likely to show positive year-on-year comparisons. But will this spur companies to continue to maintain improved performance levels to avoid negative comparisons in future years or foster complacency if their targets are met early? With sustainability increasingly driving investor decision-making, this will be a tough decision for companies placing value on ESG performance but under pressure to make up losses from the downtime.

4. Uncertain carbon markets undermine low carbon push

Carbon markets are down to their lowest point in two to three years as energy demand falls. This risks repeating a glut of surplus credits similar to that the EU emissions trading scheme (ETS) had after the financial crisis, which weakened the commercial case for low carbon investments and effectively allowed companies to pollute for free. Regulators will need to tinker in the markets, potentially introducing mechanisms to remove surplus credits similar to the EU’s market stability reserve. The uncertainty could also put off countries looking to launch schemes or expand emissions trading schemes a severe blow for global climate action, which hinges on expanding carbon pricing.

5. Opportunity for renewables hinges on recovery policies

In the short term, corporate investments in renewables may tail off amid more immediate financial concerns and falling power demand. But, countries will look to major infrastructure projects to kickstart their economies after the pandemic. Much will depend on whether lawmakers aim to prop up the status quo or grasp an opportunity to rewire their economies to support a low carbon transition. The United States’ USD2 trillion stimulus package has largely missed the mark on low carbon, but China and the EU are more likely advocates. Indeed, China’s 14th five year plan, covering 2021-2025, has the potential to be the most important climate policy document in history to date.

6. Respite from climate protests – for now

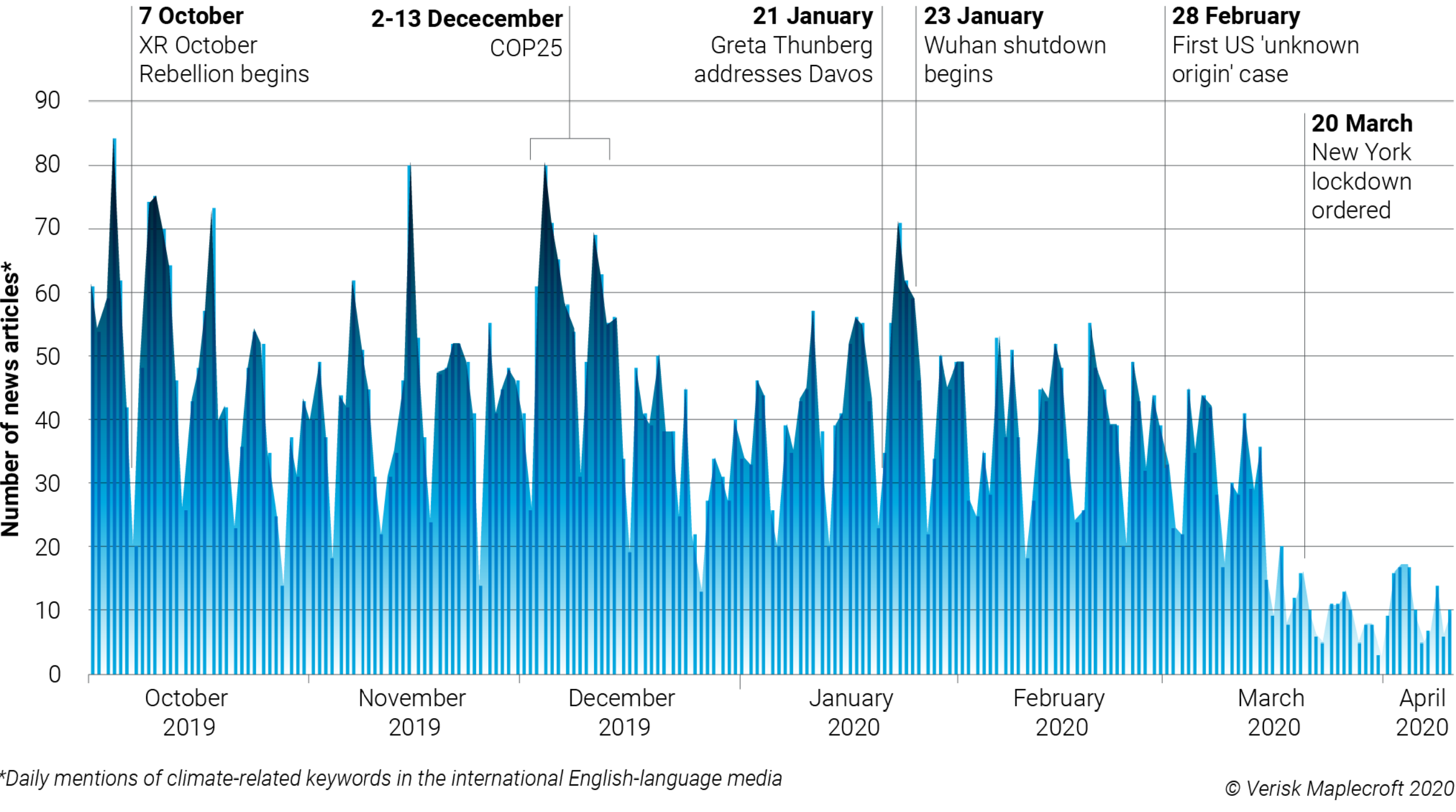

Lockdowns and self-isolation measures have pushed the climate action movement that gained so much momentum in 2019 off the streets and onto online platforms. While this doesn’t negate the potential for disruption via social media channels and cyber attacks, striking at home school doesn’t grab media attention. In the first three months of 2020, the number of media stories referencing ‘climate change’ plummeted. The absence of visually compelling protests lifts external pressure on companies for the time being. However, we would anticipate a boom in post-lockdown street action as in-person interactions take on a new level of appeal.

7. Business travel grounded for good?

The impromptu worldwide experiment with home working will change corporate culture for many businesses. Companies will certainly appreciate the boost for corporate carbon goals and reduced operating costs as workers become accustomed to Skype and Teams in place of travel and in-person meetings. The extent to which this will continue depends on how companies weigh these benefits against the loss of social capital that comes from meeting face to face. It may be too soon to predict a fully decentralised workplace, but large travel overheads and significant investments in corporate real estate will certainly start to be questioned.

A test of commitment to the low carbon transition

Clearly, the climate agenda in the post-virus world will have shifted from the standard experience so far. Whether it’s for better or for worse will depend on how long the restrictions last and how governments and business choose to recover from the economic damage sustained. The concern for long term climate goals is that economic recovery is seen as the only imperative and sustainable growth is put to one side.

2020 can still be a transformational year for the climate if businesses are prepared to step up to the plate, recognise that we can’t go back to business as usual, and look beyond the current crisis with the aim of avoiding the next one.