Russian-aligned African states face worsening social and governance profiles

by Eric Humphery-Smith and Maja Bovcon,

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has thrown sub-Saharan Africa into another round of Cold War dynamics. While the West is ramping up sanctions on Russia in a bid to force the Kremlin to end the war, the increasingly isolated Putin regime is scrambling to secure the support of its allies in the region.

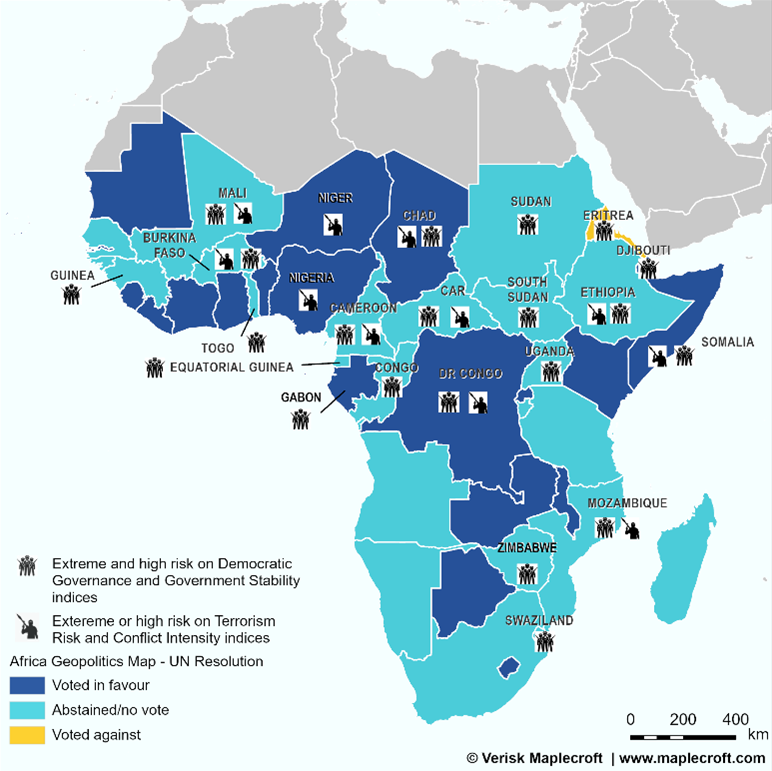

Renewed tensions between Moscow and the West threaten to destabilise the African countries that fall within Russia’s sphere of influence – the majority of which have poor social and governance credentials. Indeed, 75% of the countries in the extreme risk category – and eight of the 10 worst performing countries - on our Democratic Governance Index (DGI) did not vote in favour of the UN Resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Continued alignment with Moscow carries the risk of isolation from global markets. But a host of African states are heavily reliant on Russian extractives projects and military assistance, limiting their ability to cut ties with the Kremlin. For these countries, the uncertainty resulting from Russia’s growing isolation threatens to worsen an already bleak outlook for regional social and governance profiles.

Russia’s sphere of influence gravitates towards countries with poor governance

African countries with poor S and G credentials tend to side with Moscow. This includes autocratic (Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Angola, Zimbabwe, CAR) and military regimes (Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Sudan) - all of whom failed to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (see map below). While some countries forged links with Russia in the context of the Cold War (Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, South Africa), others have more recently fallen within Moscow’s sphere of influence (Mali, CAR).

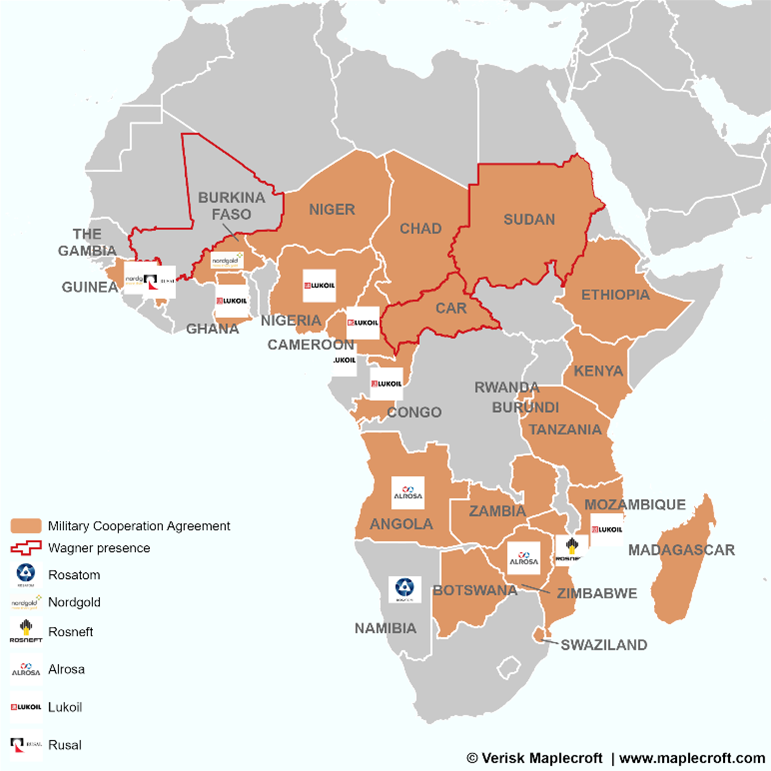

Russia primarily projects its influence through military assistance. This includes official military cooperation agreements and the sale of weapons, with Russia accounting for 44% of arms imported to Africa between 2017 and 2021. Kremlin-linked private security companies are present in several African countries. This includes the Wagner Group, which is reportedly financed by pro-Putin oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin (see below).

In return for its support, Russia is looking for access to natural resources (diamonds, gold, oil) and geo-strategic opportunities, including votes in the UN or the ability to establish military bases at strategic locations, such as the planned naval base on Sudan’s Red Sea coast.

Sanctions likely to disrupt Russia’s businesses, straining relations with host countries

We expect African countries that rely significantly on revenues from Russian extractives projects to remain pragmatic and allow their operations to continue despite sanctions imposed by the West. However, sanctions targeting Putin allies, Russian banks and certain companies and products are nevertheless likely to force Russian businesses to delay or even cancel planned investment in sub-Saharan Africa due to restricted access to capital and disruptions of supply and sales chains.

Examples from the mining sector:

- Rusal, one of the key bauxite miners and the only alumina producer in Guinea, has reported disrupted access to equipment, alumina (20% of which the firm sources from Australia) and refineries. Most of the bauxite extracted at Guinea’s Kindia mine used to be refined in the Ukrainian city of Myoklaiv, which has been under intense attack by the Russian forces.

- Nordgold group has struggled to export gold from its mines in Burkina Faso and Guinea, after Swiss-based MKS PAMP refused to refine the company’s gold over the Ukraine war.

- Sanctions against Russian government-backed Alrosa diamond company will not directly affect Catoca mine in Angola because the firm owns less than 50% of the mine. However, Alrosa’s exclusion from the US banking system and trade will reduce the company’s access to capital, likely limiting its ability to finance Catoca operations.

Examples from O&G sector:

- TotalEnergies has decided not to contract Russian pipe producer ChelPipe for the construction of the pipeline from the French firm’s Tilenga oil project in Uganda to Tanzania’s port of Tanga.

- In 2019 Lukoil was awarded a licence by the Equatoguinean government to develop the Fortuna gas field, but it is increasingly unlikely to find the finances and partners needed to finally kick-off the project. Restricted access to credit will also make it difficult for Lukoil to honour its cash calls on Eni-operated fields on Marine XII block in Congo.

- While Rosneft and Novatek qualified in April 2022 for Mozambique’s sixth licencing round, sanctions against Russia increase the chances that their bids will not be successful.

A shortfall in state revenues due to project delays or cancellations by Russian companies are likely to irritate host governments, putting pressure on their relationship with the Kremlin. This is particularly true for countries such as Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Mozambique, where there is reported interest in investment from other operators.

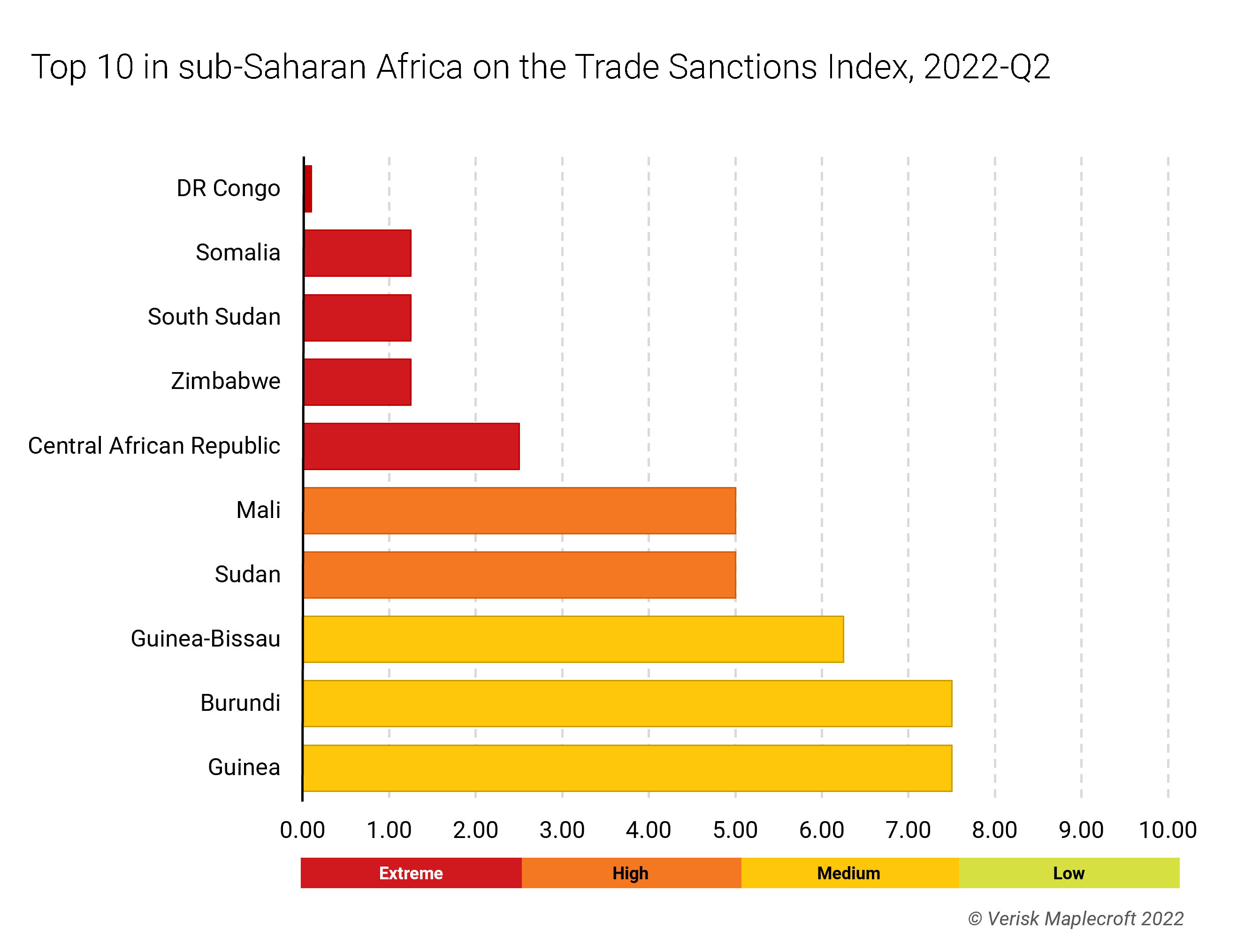

Russia betting on disinformation and military cooperation

Due to Russia’s increasing diplomatic and economic isolation, the Kremlin will likely try to preserve its sphere of influence in Africa by concentrating its disinformation campaign and military assistance in key jurisdictions. Resource-rich fragile states, some of which are themselves subject to international sanctions - including Mali, CAR and Sudan - are particularly susceptible to Moscow’s advances (see below).

Yet, while the provision of military personnel training and the transfer of technology are unlikely to suffer, sanctions imposed on the Russian defence industry will likely undermine the delivery of military equipment and impair its repair and maintenance support. Any major disruptions to the delivery of Russian military hardware are likely to prompt African countries to diversify their supply base away from Russia, most likely in favour of China and the West.

Sanctions affecting legal Russian businesses are also likely to result in a proliferation of illegal activities by Wagner mercenaries as an alternative source of revenues and gold reserves, as well as intelligence and diplomatic services for the Russian government.

Russia’s fight to retain influence set to bring more instability, worsen governance

Even before the Ukraine war, Russia’s sphere of influence in sub-Saharan Africa relied significantly on military cooperation with regimes with poor S and G records. Russia’s increasing isolation is likely to worsen this trend. African countries are likely to distance themselves from Moscow in the event that sanctions on Russian businesses cause a shortfall of revenues due to project delays or cancellations. Fragile states are more susceptible to Russian disinformation campaigns and will continue to welcome its state or para-statal military support in exchange for mineral resources.

Yet the proliferation of such activities is likely to further destabilise these countries and exacerbate their governance risks, making them even less attractive for ESG-beholden investors. Indeed, aligning with Russia will restrain these countries’ access to the Western financial system and markets, which will have negative consequences for sovereign debt performance and investor confidence.