Rising legal risks up the ante for corporates bluffing on human rights

by Sofia Nazalya,

Ever since the endorsement of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) a decade ago, the conversation on corporate accountability for human rights abuses has seen remarkable shifts. In the last ten years, human rights due diligence laws have developed and evolved rapidly, reflecting increasing expectations of businesses to perform better. We are now reaching the stage where just identifying human rights risks in their supply chains might not be enough though. Moving forward, companies are going to have to play more of an active role in mitigating these risks and enhancing their social footprint to prove their sustainability credentials to consumers and investors.

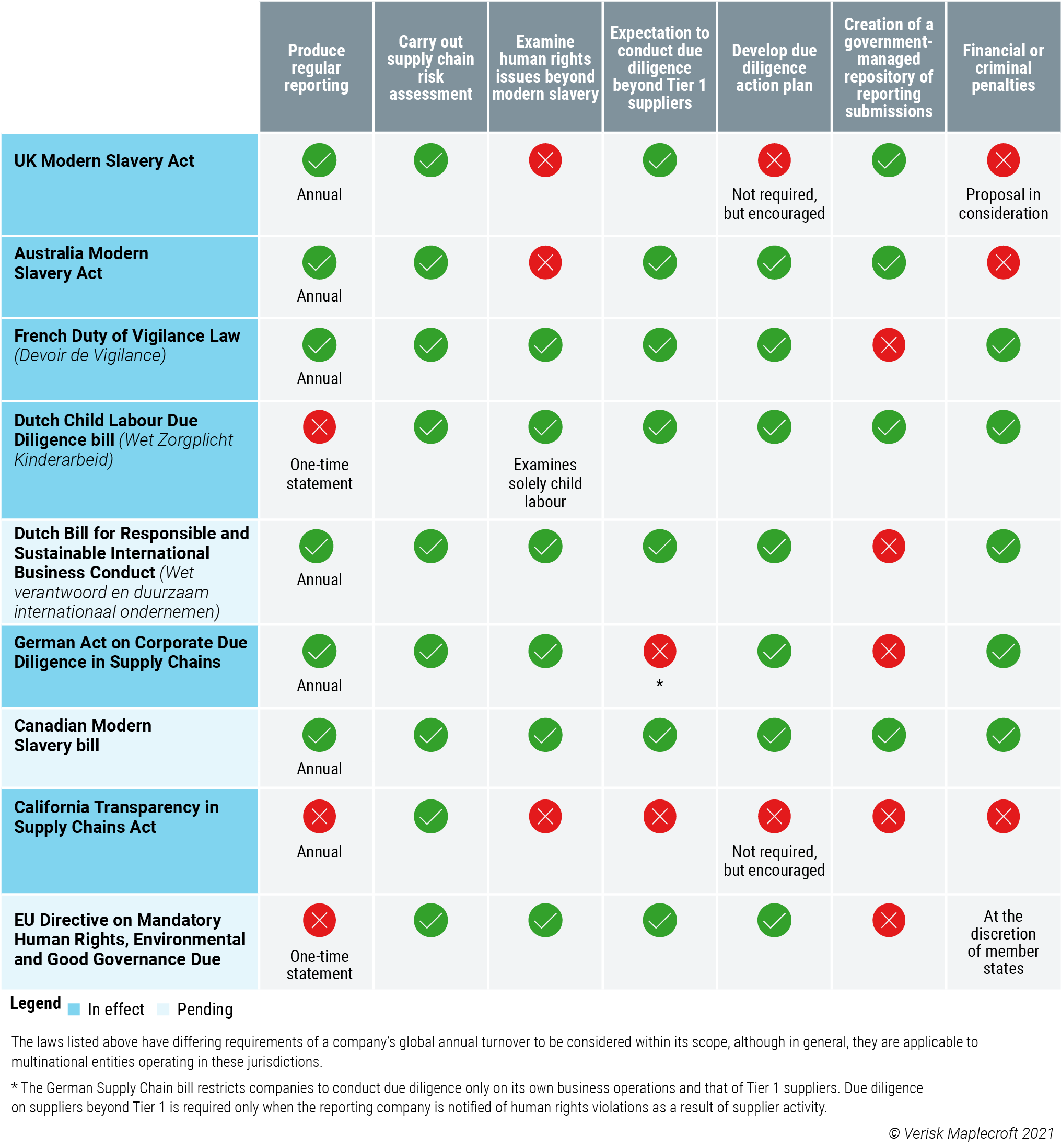

Getting ahead of new and emerging legislation will be key to this. We’ve mapped out nine leading human rights due diligence laws that have far reaching implications for large companies, giving a more comprehensive picture of current and upcoming obligations. By examining these laws – that are either already in effect or are expected to be enacted in the next year or two – we assess their scope, coverage and applicability to help companies understand where they are and, most importantly, where they need to get to.

More rigorous legislation on the way

As illustrated above, companies must navigate through a complex web of legal requirements that involve various standards of mandatory reporting and due diligence requirements. The French Devoir de Vigilance law is the most stringent and comprehensive human rights due diligence law currently in effect. Unlike the UK and Australian Modern Slavery laws, the French law requires companies to not only carry out internal supply chain risk assessments, but also imposes financial penalties in the event of non-compliance.

Increasingly, we are seeing emerging legislation taking a leaf out of the Devoir de Vigilance book by way of adopting a more rigorous approach that aims to hold businesses to account. As the Dutch, German, Canadian and EU bills suggest, laws are trending towards imposing financial or criminal penalties, and increasingly expect companies to develop action plans in response to identified violations.

Another trend is the tendency for human rights laws to now encompass issues far broader than modern slavery alone. As with the French Devoir de Vigilance, European companies are increasingly expected to perform due diligence on a diverse range of both human rights and environmental issues. Companies must therefore prioritise the use of credible ESG data to accurately inform their risk assessments.

At the heart of these legislative shifts is a push for compliance designed to genuinely eliminate, or at least reduce, human rights violations, with companies expected to take a leading and active role. Companies will therefore face a more comprehensive landscape of human rights legislation that will increasingly carry greater material risks in the event of non-compliance. More rigorous laws demand companies to reframe their approach to human rights. The conversation changes from one primarily concerned with public relations fallouts, to a more holistic framework that incorporates legal, financial, and ethical perspectives.

Landscape to rapidly change in next few years

Several key developments are likely to take place in the coming years. The aforementioned bills are likely to be enacted in 2022 to 2023, including the EU Human Rights Due Diligence bill, which will be the first to mandate human rights due diligence on an EU-wide level. Once the EU Directive becomes law, more EU member states are likely to enact their own human rights due diligence laws, however the strength and scope of these will vary greatly from state to state.

Proposals to introduce fines to the UK Modern Slavery Act will likely be approved within the next six months to a year, which will add some long missed legal teeth. We expect that financial or criminal penalties will increasingly be the norm with future human rights legislation to ensure greater corporate accountability. As with the German bill, where fines can go up to 2% of a company’s annual revenue, future laws are likely to include severe penalties that go beyond a mere slap on the wrist.

Amendments to both the UK and Australian laws are increasingly likely in coming years, although uptake may be slow. More robust requirements, such as establishing minimum standards of supply chain transparency, will be driven by increasing domestic pressure for greater corporate accountability, but also as a response to global events – not least, high-profile forced labour and human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Find out more about our Human Rights risk indices

Loopholes hinder corporate accountability

While stronger laws are a step in the right direction for enhanced corporate social performance, legal loopholes will continue to weaken accountability. The German Supply Chain Bill’s limitation of conducting due diligence only onto Tier 1 suppliers, for example, effectively disincentivises companies from proactively examining their entire supply chain – particularly as human rights risks tend to increase when examining upstream or secondary suppliers.

A key differentiator of the EU Directive is the inclusion of SMEs in its scope, broadening the range of companies required to perform due diligence. While it’s likely that this provision may be excluded from the final text, it signals that smaller enterprises may no longer be given a ‘free pass’ in the future. The current exemption of SMEs in these laws has and will continue to a be a rallying point for civil society observers. It is certainly not outside the realm of possibility that smaller enterprises will one day be bound by the same due diligence standards as MNCs.

Only the beginning for ‘S’ in ‘ESG’

As due diligence requirements become increasingly stringent, companies that stay ahead of the curve will not only find greater success in mitigating risk, but also in enhancing their social impact. These laws are only the first link to an evolving chain of tools targeted to improve not only corporate social impact, but environmental performance too. As governments and investors alike prioritise sustainability, the ‘S’ in ESG will become an increasingly important component. This is where the increasingly intricate web of human rights laws will have a transformative impact on the way companies do business. For some, this means simply ticking boxes will no longer be enough.