Rising food costs will fire up Africa’s civil unrest hotspots

by Indigo Ellis,

Africa’s hotbeds of protest are set for a torrid year. A perfect storm of economic issues and discontent with government are gathering on the near horizon in countries across the region, but the catalyst is going to be food.

The economic knock-on effect of the pandemic on governments and populations is manifest. Falling government revenues and lockdown-related restrictions will have a devastating effect on food supplies, resulting in inevitable price rises that populations can ill afford. The countries most reliant on food imports, as well as those reliant on remittances from their diasporas, are the ones that will feel the greatest impacts.

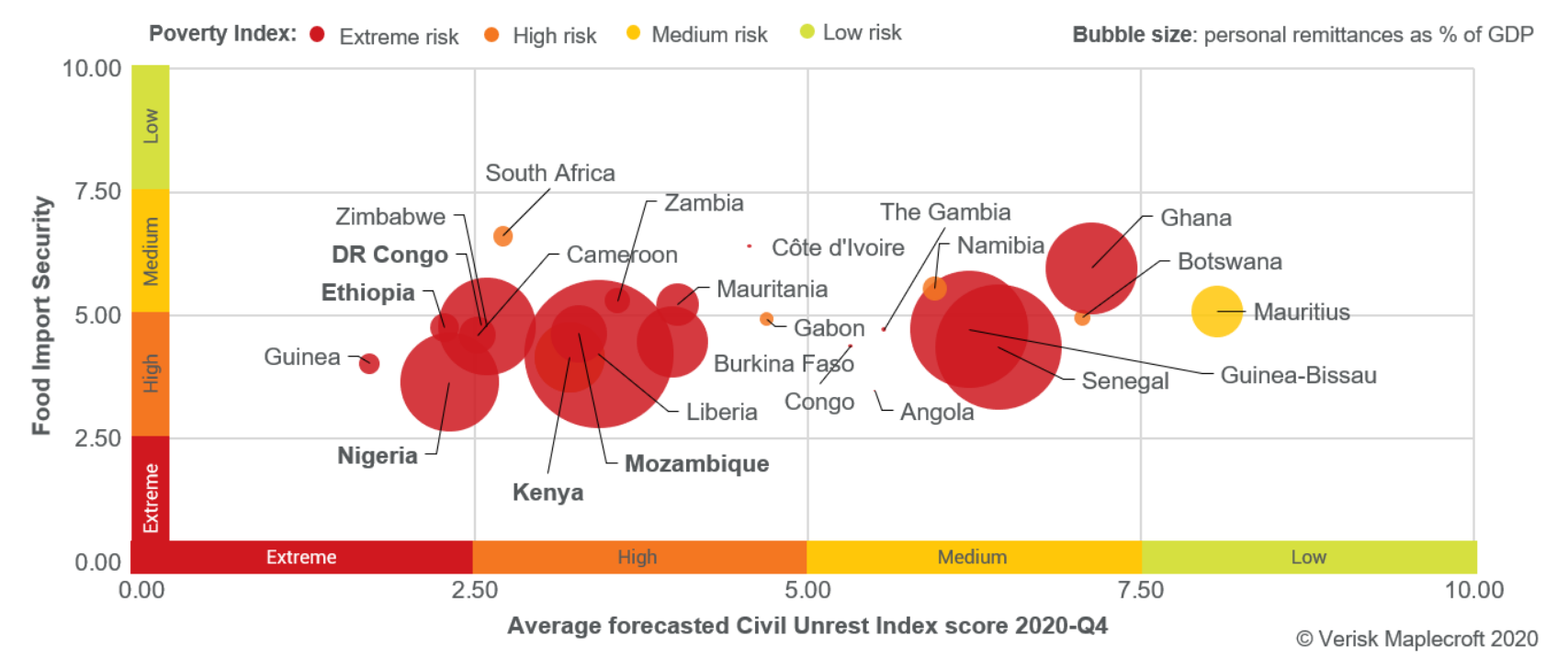

Among these are the continent’s existing hotspots for civil unrest. Nigeria, DR Congo and Ethiopia are already rated extreme risk in our Civil Unrest Index for 2020-Q2, but their scores are forecast to deteriorate over the coming weeks and months. Why? Each is also categorised as high risk in our Food Import Security Index, leaving the countries very much exposed to the fluctuating markets created by COVID-19. Kenya and Mozambique are the other ones to watch – we rate both only high risk for civil unrest currently, but their scores have the potential to deteriorate significantly since food supplies could worsen further due to locust swarms in Kenya, and Mozambique’s prolonged recovery from last year’s cyclones.

Read our article 'Latin America in line for huge surge in civil unrest'

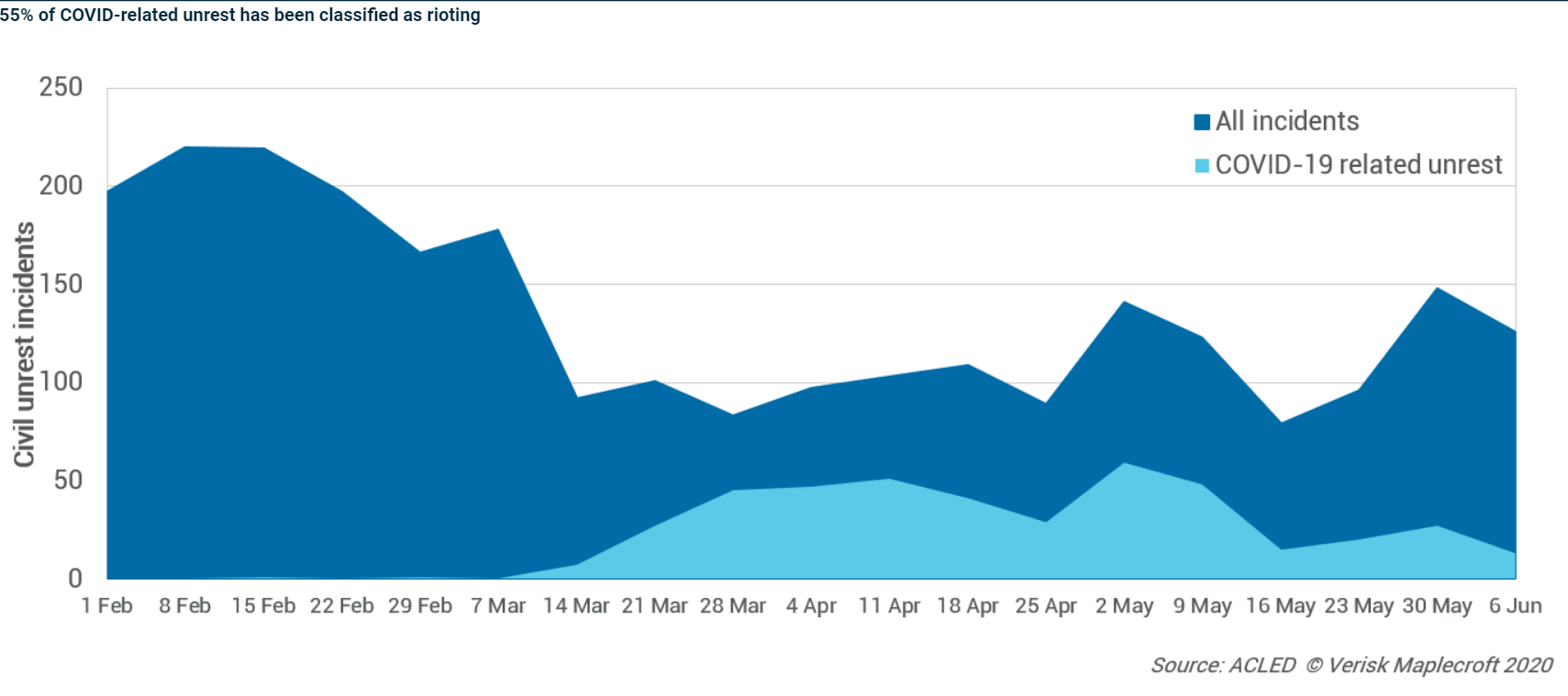

Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, our 2020-Q2 civil unrest data showed that these five countries’ scores were improving or static compared with 2020-Q1. But that is set to end.

Ethiopia, Nigeria and DR Congo are 4th, 5th and 6th highest risk among the 49 sub-Saharan African countries, and their ranking is liable to worsen as the full scale of the pandemic hits the continent. Kenya and Mozambique, sitting at 10th and 13th respectively, are likely to enter the top 10 highest risk by 2020-Q4.

Extreme poverty levels exacerbate the risks of unrest across all five, as do the nations’ inability to guarantee adequate food supplies. As lockdowns loosen, but secondary impacts of the coronavirus pandemic bed in, our 2020-Q2 Civil Unrest Index projections indicate that over the next six months these countries are more likely than other sub-Saharan African countries to witness instances of unrest motivated by food insecurity.

Companies operating in Ethiopia, Nigeria, DR Congo, Kenya and Mozambique, particularly in urban areas, will face operational disruption. Delays to transportation and road blockages are highly likely. An extreme risk scenario means reduced government stability, leading to policy uncertainty and an unpredictable operating environment.

Large informal workforces make urban centres hotspots of unrest

In Nigeria, we expect the rolling lockdown measures in Lagos, Abuja and Kano – breeding grounds of COVID-19 – to guarantee these areas remain the centres of unrest over the coming months. Lagos has seen food prices rise by up to 50% in some cases. Increasing rice production (up by an average of 1.8 million tonnes from 2017-2018) is still insufficient to feed Africa’s most populous country.

The biggest cities are similarly vulnerable in Kenya, with the worst inflationary pressures being felt in Nairobi and Mombasa, where total lockdown remains in some key neighbourhoods. At the same time, food production has been seriously impacted by extensive flooding and population displacement, as well as the ongoing devastation wrought by locust swarms.

In DR Congo, rising food prices have led to unrest in Kinshasa and some larger cities, including mining hub Lubumbashi – though the worst of the food price inflation will be felt in the restive eastern provinces, where border closures have stymied informal trade with Rwanda, a key food provider to the citizens of Goma.

We see a similar picture emerging in Ethiopia, where the state of emergency has drastically reduced the informal activities on which the incomes of most poor urban households depend, making it impossible for them to meeting the rising cost of food.

Anti-government sentiment will rise as food availability falls

While we do not foresee food security-related unrest rising to untenable levels in any of the countries mentioned here, we do expect it to impact popular support for and therefore the stability of governments. In Ethiopia and Mozambique, in particular, food insecurity will contribute to the destabilisation of both local and national governments. The fragile Renamo-Frelimo peace agreement will be tested as food supplies fall in Mozambique’s four pro-Renamo provinces, while food insecurity will add fuel to the fire of anti-government sentiment in Ethiopia, already at a high during the countrywide state of emergency.

And we may just be at the beginning of this unrest. The pandemic is still in full swing in sub-Saharan Africa, and its fallout will worsen inequality continent-wide and spur further unrest. A young, jobless population will be disproportionately affected, and as we have seen across the world, disenfranchised young protestors can be a catalyst for regime change.