Reform uncertainty in Brazil points to economic challenges ahead

by Jimena Blanco,

What are the implications for Brazilian mining, oil and gas?

Brazil’s two major extractive industries are out of sync and are experiencing the evolving business climate under President Jair Bolsonaro in different ways.

Oil and gas tenders in Q4 include the so-called transfer of rights areas, considered one of the world’s most promising offshore prospects. Meanwhile NOC Petrobras is moving ahead with plans to privatise eight refineries.

In mining, recent tragedies have left investors reconsidering their exposure to the country. BHP's co-owned Fundao tailings dam, which collapsed in 2015, is a prime example. BHP faces a new US$5 billion class action claim for damages in a UK court.

The more recent collapse of the Brumadinho dam last January has negatively impacted growth for the sector. Vale, the owner of Brumadinho, stopped production across a range of mines because of court orders demanding further safety checks.

Brazil's oil and gas investment energises the economy

Combined, the two extractive industries represent around 20% of GDP, so their fate is critical for the wider economy. Their different stories come at a time of nervousness over the government’s economic performance. Despite promising to pursue business-friendly policies, the new administration has been distracted by internal disagreements and has moved slowly on delivering change.

The good news is coming from the Brazil's oil and gas sector, which is poised to deliver the big investment inflows that the new right-wing government wants to see. This will help energise the country’s still weak economic recovery, with signing bonuses for three offshore rounds due in October and November projected to bring in USD 47 billion. Petrobras’s refineries could attract a further USD 20 billions in funds.

Safety concerns in the mining sector tell a different story

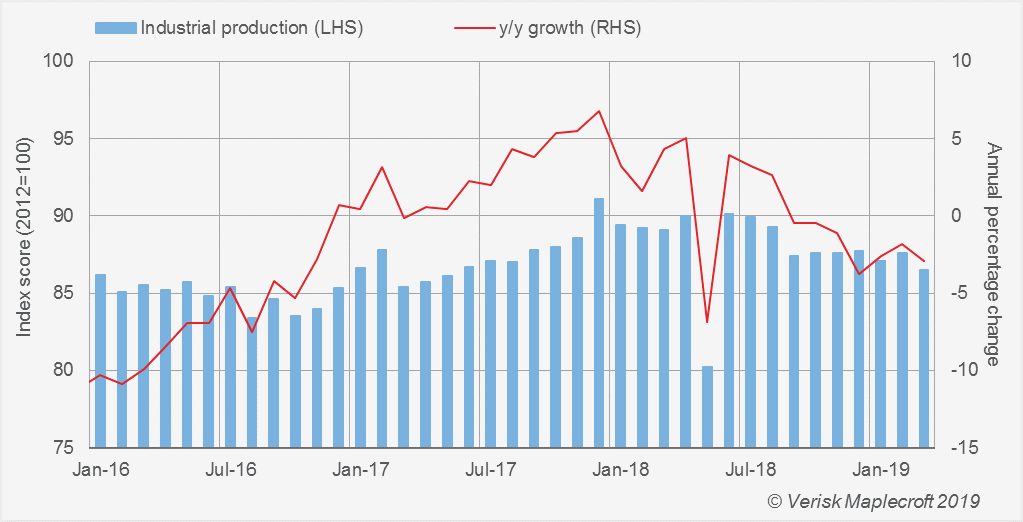

The mining story is more problematic for Brazilian mining companies, with the catastrophic failure of two tailings dams having an adverse knock-on effect on the wider economy. Lost production and shortages in Brazil’s steel and equipment industries contributed to the 2.2% fall in industrial production in Q1.

Disagreements within the cabinet are increasing the risk on sub-par macroeconomic management. Pension reform – the single most important determinant of future growth - will take much longer to get through Congress. A recent battle over control of Apex, the trade and investment agency, has resulted in the appointment of three leaders in five months. The latest head, retired Rear Admiral Sergio Segovia, begun by sacking Apex officials previously appointed by the foreign minister.

Despite these tensions, the administration has made some tepid progress such as the drafting of an “Economic freedom decree”, a new measure cutting red tape. It removes the requirement for operating licences when the activities concerned are deemed to be “low risk”.

Will the Bolsonaro government deliver economic growth in Brazil?

The economic outlook is a decidedly mixed picture. The market consensus is that economic growth prospects have been steadily deteriorating, falling to 1.49% in the latest Central Bank survey (from over 2% in January). Moreover, uncertain business confidence will keep any progress in reducing unemployment at a slow pace, with 2019-Q1 remaining at a high rate of 12.7% (but a little lower than the 13.1% registered in 2018-Q1).

Nevertheless, the bulk of the business community still trusts that the Bolsonaro government will eventually deliver what it needs. A survey of 1,000 members of the business community commissioned by BTG Pactual bank found that 59% believe the government’s performance has been “good” or “great”, notably higher than the 39% approval rating given the new government by the public at large.

Current growth is likely to continue disappointing if internal government bickering endures and the administration lacks positive news stories to tell – such as a delay in the pension reform, which should clear its first vote in the lower house by end-Q3.

Successful oil and gas auctions in October/November could also build positive momentum. But the government will need to take other actions, such as accelerating its planned privatisations, to keep the private sector expectations positive.