Public grip on water security tightens in Chile, risking mining supply

by Mariano Machado,

Chile has entered the 10th year of its worst drought in six decades, and the country is expected to face more extreme and the most severe water stress in the Western Hemisphere over the next 40 years. Access to water is a massive challenge, particularly in Northern Chile, and improving the management of the country’s resources is key to balancing water security for its citizens as well as for key mining operations.

Over the past two decades, piecemeal attempts to reform the 1981 Water Code – the cornerstone of water governance – failed to quell the public controversy and, instead, eroded the legitimacy of the system itself. Furthermore, an excessive number of failed efforts have now refuelled the focus of new generations on the issue of how Chile’s water resources are managed.

The latest strain of debates has focused on desalination – currently, the most reliable solution to overall scarcity – and particularly on the ownership of processed waters.

Indeed, on 5 April, the Senate resumed the debate on a parliamentary motion to establish that the water produced via desalination is a national asset for public use. In other words, that this water would be publicly owned and that access to it would be guaranteed to all Chilean citizens – in line with the parallel goal of enshrining such a principle in the Constitution and steering away from the current approach regarding water rights as private property.

The bill, if approved, would alter the rules of what was perceived as the solution to extreme water scarcity in Chile's northern mining hub.

Investment in desalination could be jeopardised

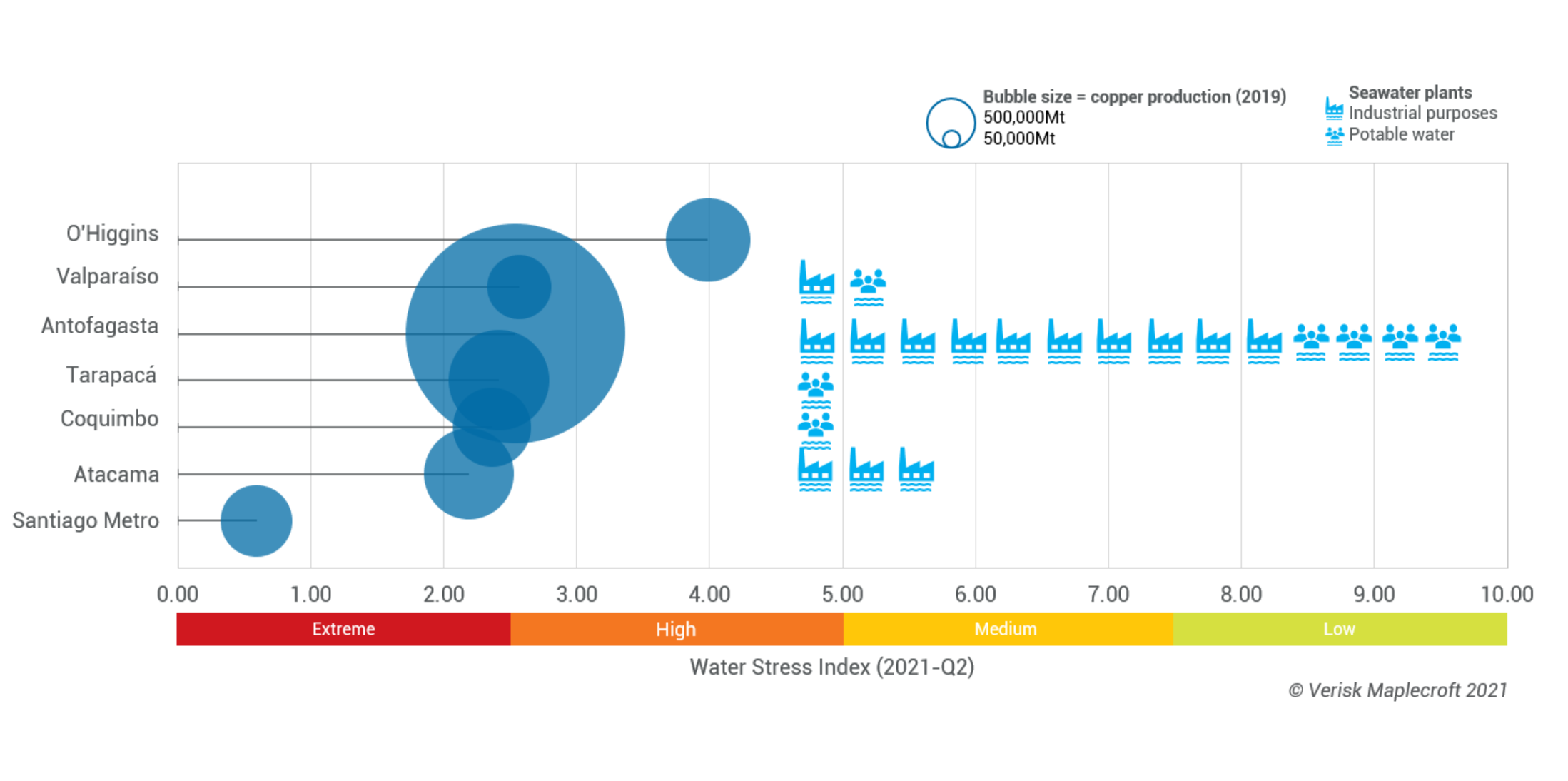

The use of seawater in Chile has increased – on average – 43% per year between 2010 and 2019. With 100% of Chilean copper production occurring in high or extreme water stress regions (see below), the mining sector has spearheaded this increase in seawater usage and owns 14 of the country’s 23 desalination plants.

The trend looks set to continue, and Chile’s copper commission, COCHILCO, estimates that USD3.25 billion expected investment in new desalination facilities could come online by 2028. This would mean that roughly half (47%) of the sector's non-recirculated water use would come from seawater by 2031 – a 14 percentage point increase from current levels.

But desalination plants are capital-intensive projects, and should regulatory frameworks remain in a state of flux as part of Chile’s ongoing change process, current discussions risk delaying investments in new facilities.

The main deterrent to investment is that – should the bill pass– operators could see the water from plants being redirected by the state to cover shortages, regardless of the public or private nature of the facility processing it. Water scarcity is already a reality in northern Chile, and climate change is set to increase water stress levels in the coming decades.

Even if the public sector decides to lead the charge on the massive investments required to increase desalination capacity, tensions with local communities around the impacts of removing salt from the waters off Chile’s shores could create barriers for securing needed private funding from foreign investors. Chief among societal and environmental concerns is the effect on fisheries and coastal livelihoods of dumping the concentrated water produced by desalination back into the ocean.

Debate around water governance will remain unrelenting

Discussions on the bill will carry on throughout 2021-Q2, with the Special Committee on Water Resources expected to issue a complementary report on the bill by late April.

At this stage, it is very hard to say what the outcome of the vote will be, but what’s clear is the scale of the overhaul being considered. Hence, regardless of the outcome, the debate around changing Chile's fully privatised water ownership and management will continue its unstoppable march through all available channels – both in Congress and in the soon-to-be-formed constituent body, charged with drafting a new Constitution.

At the same time, we expect President Piñera’s administration to continue devoting relentless efforts to funnel the conversation toward executive-driven initiatives, seeking to shape the discussion during the rest of his term (until March 2022) and the first half of the constituent body's drafting process. The recent upgrades to the institutions dealing with water issues – including the creation of the Ministry of Public Works and Water Resources, and the promotion of the former Water General Directorate to Undersecretary level – underpin our views on the government’s efforts to drive the conversation.

These congressional discussions are also setting the stage for discussions in the constituent body. With more than half of the candidates for the constitutional convention willing to introduce changes to water governance, we expect a cross-party ‘water bloc’ to emerge at the core of the drafting body set to guide the conversation and craft the necessary two-thirds majority required to approve changes.

Consequently, changes to water governance are not a matter of if but when, how radical will they be, and how much time will users and rights holders have to adapt to the new landscape.