Political risk to curb African green hydrogen potential

by Eric Humphery-Smith and Hamish Kinnear,

Well before a deal was struck at COP26, green hydrogen was attracting global attention. To its advocates, green hydrogen is seen as the only viable option for weaning heavy industry, transport or even heating off fossil fuels. Whether green hydrogen production can be scaled up, however, depends largely on how and where its two key inputs – water and clean energy – can be sourced.

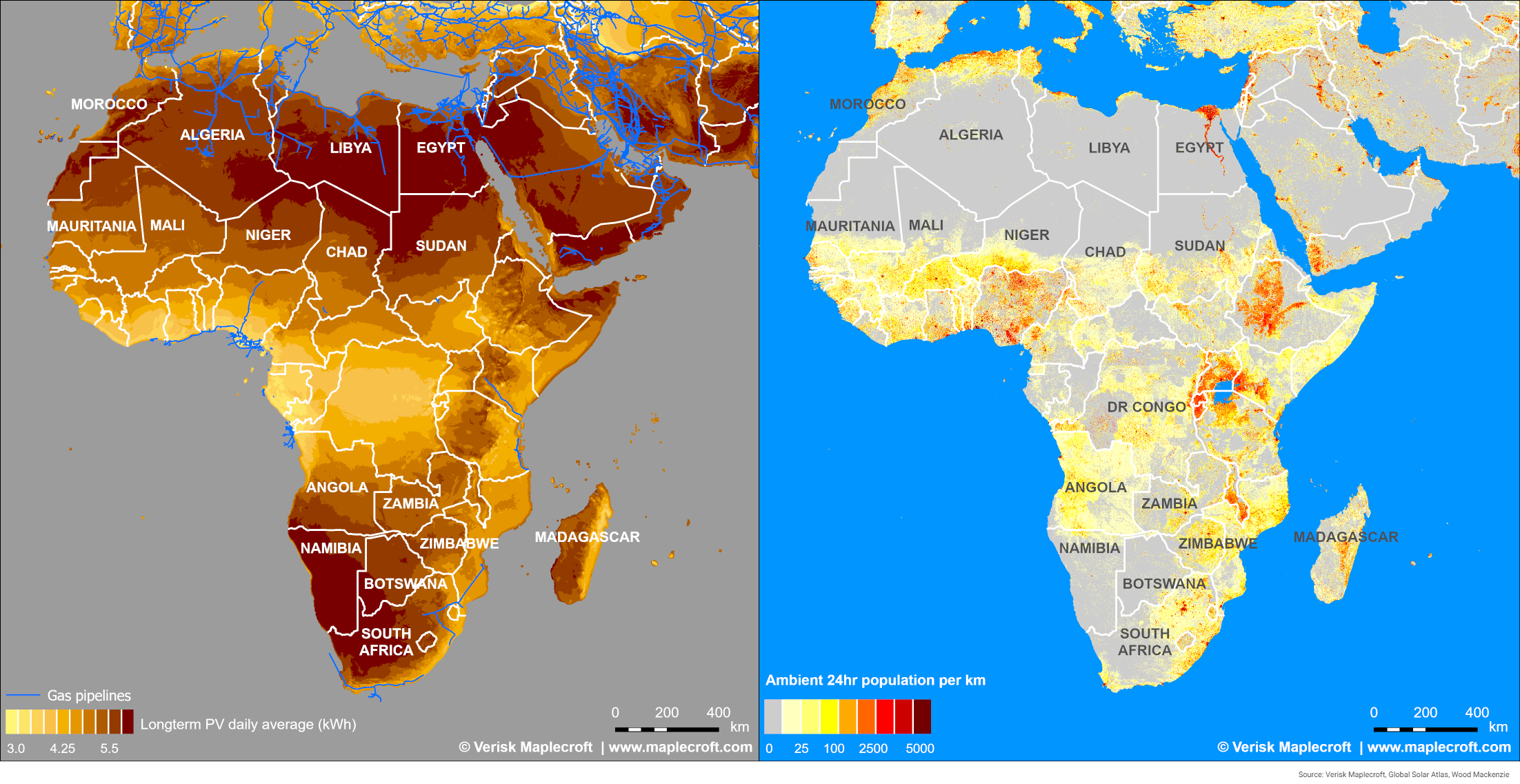

A string of lofty strategies and memoranda of understanding (MoUs) suggest that there is no shortage of interest in Africa being a future hub of green hydrogen production, particularly North Africa and Namibia. High solar potential, low-cost land (we refer to population density as a proxy) and its proximity to European markets are key advantages (see maps below). Few projects, however, have a timeline for launch, and the stratospheric capital requirements will be hard for investors to meet. We examine just how (un)realistic the drive for green hydrogen in Africa is.

Why are investors seeking out Africa for green hydrogen?

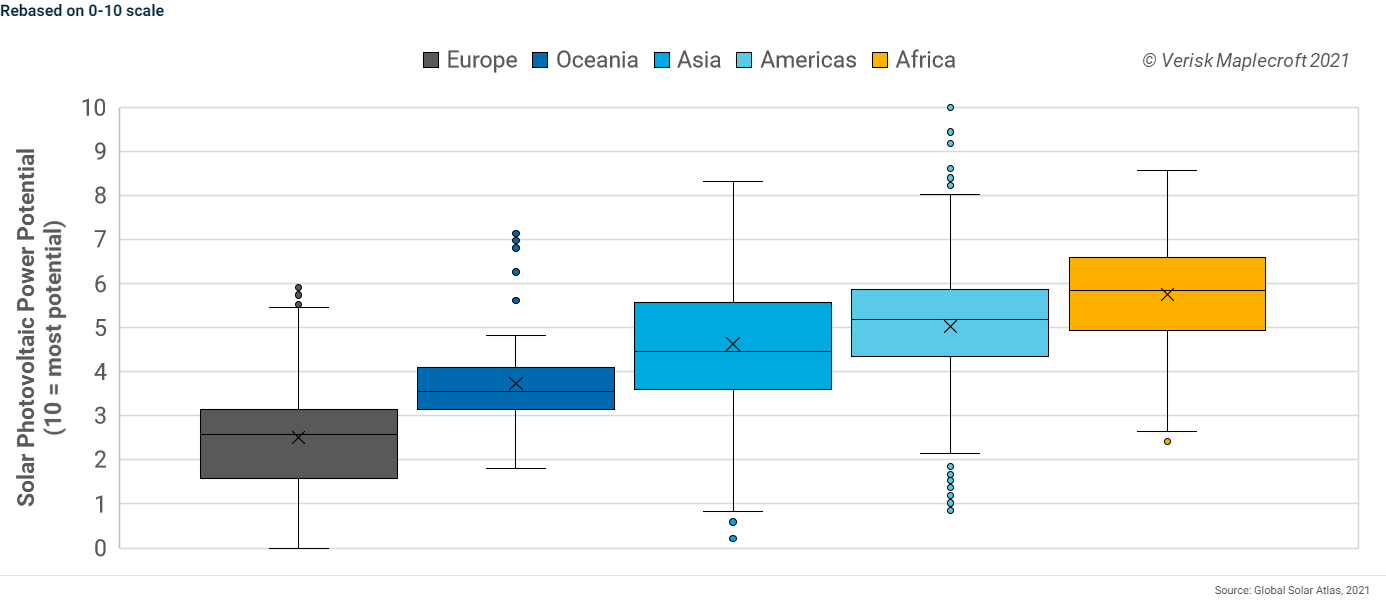

High solar irradiation is the main factor pushing green hydrogen ambitions in Africa. Chile, Bolivia and Argentina have the areas with the highest solar irradiation on the planet, but as can be seen in the chart below, the average on the African continent is far higher.

What sets Africa apart from the Americas in terms of potential scale is its proximity to Europe, a major future demand centre for hydrogen. According to a comparison of energy scenarios by the EU Joint Research Committee, hydrogen and derived fuels will account for between 10% and 23% of EU's energy consumption in 2050. This is especially pertinent for North Africa, where export costs are likely to be highly competitive if producers can use or upgrade existing gas pipeline infrastructure or liquefaction facilities.

Africa also has the sparsely populated deserts to host the colossal solar farms required to create the energy necessary to produce green hydrogen. The largest projects to be announced in the last year alone – in Mauritania and Namibia – total over USD50 billion and illustrate this confluence of favourable conditions to develop mega-scale photovoltaic solar projects.

The catch is that accessing European markets depends on how the EU progresses with its own strategy, which currently does not factor in future African supply. Rather, the EU Hydrogen Strategy launched in July 2020 seeks to be mostly self-sufficient and targets Eastern Europe (and in particular Ukraine) as the priority investment area for green hydrogen.

E and S factors a potential hurdle, but not for all African markets

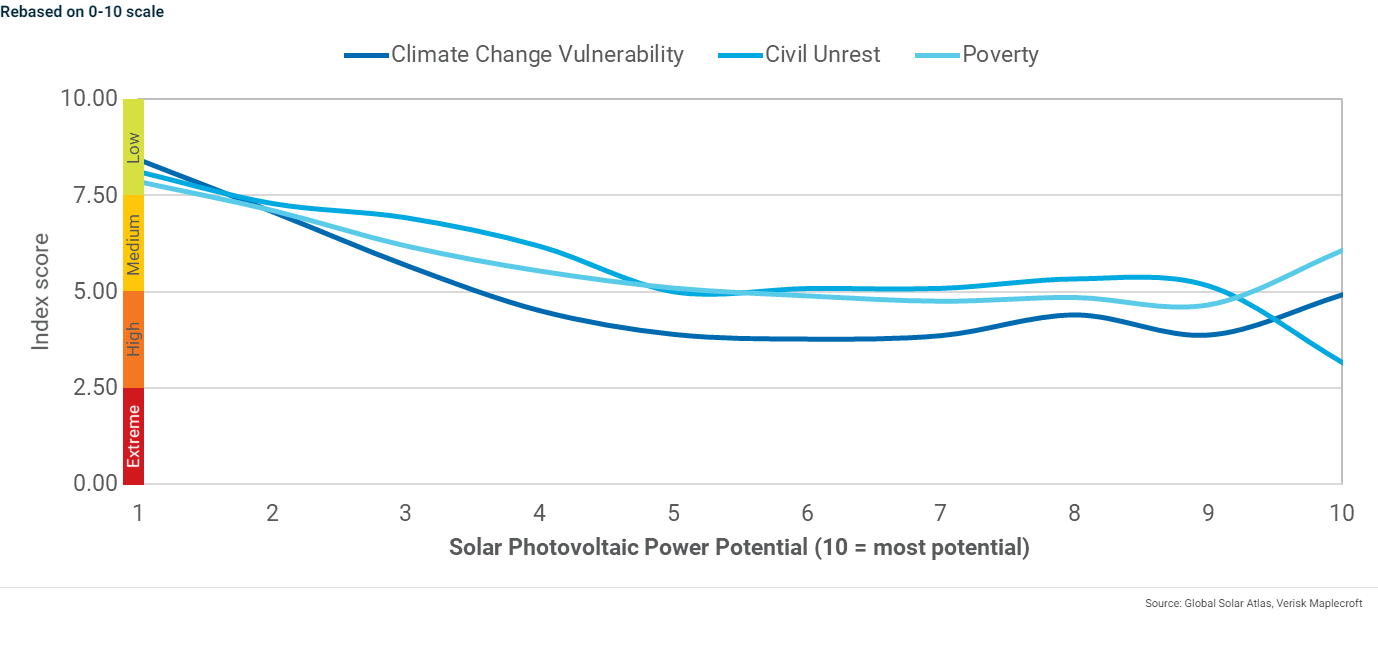

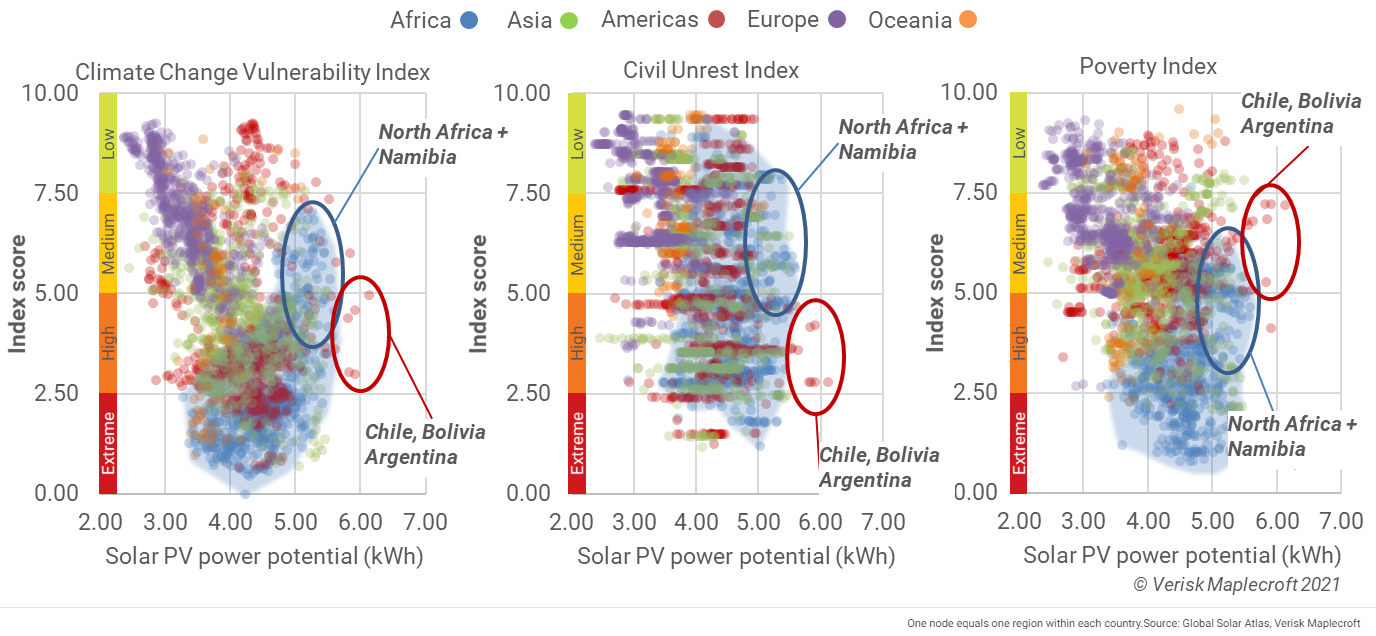

A global analysis of our data shows that there is a moderate correlation between a country's performance on our environmental (E) and social (S) indices and its solar power potential. The strongest correlation is with our Climate Change Vulnerability, Poverty and Civil Unrest indices: the chart below shows that, on average, these risks are highest in countries where the solar power potential is also higher.

In Africa, however, the areas with highest solar power potential are the least risky on each of our Climate Change Vulnerability, Poverty and Civil Unrest indices, and less risky than Chile, Bolivia and Argentina. For example, large-scale solar investments in South America are more likely to be exposed to climate risks such as desertification and sea-level rise, and to disruption from protests. Poverty levels in North Africa and Namibia exceed those in South America but are markedly lower than in the rest of Africa, which will help mitigate social risks for green hydrogen developers (see chart below).

Political instability weakens prospects for North Africa

While North Africa has the potential to be the most competitive subregion on the continent, geopolitics and civil strife could stifle green hydrogen initiatives. Algeria and Morocco, for example, remain at loggerheads over Western Sahara, and a gas pipeline linking the two – the only substantive economic connection between the countries – was closed in October. In Algeria itself, a poor regulatory environment alienates most businesses other than the oil and gas sector. An uncertain political outlook for Libya and Tunisia rules out most greenfield investment for now.

This leaves Egypt, Morocco and Mauritania as the most viable investment destinations for green hydrogen projects in North Africa. Egypt is formulating a green hydrogen strategy and will have the chance to showcase its efforts as it hosts COP27 next year. Morocco is also looking into the viability of exporting green hydrogen and signed an MoU with Germany in June 2020 for the development of the sector, but it may end up trimming its ambitions and use domestically-produced hydrogen to produce 'green' ammonia and fertiliser instead.

Mauritania is the leader on the continent in terms of private investment commitments, with over USD40 billion announced, but this is almost exclusively in the form of non-legally binding MoUs. These projects therefore remain hard to visualise given the authorities' historical difficulties in attracting and securing investment at this scale across a wide range of sectors.

By contrast, the announcement by the Namibian government to appoint HYPHEN Hydrogen Energy as the preferred bidder for a USD9.4 billion green hydrogen project, in a competitive tender, appears to be the real deal. This could enable the Southern African region to become the out-and-out regional leader in green hydrogen production, especially given the comparatively stable investment environment. The relative geographical isolation of Southern Africa, however, may mean that finding markets will be trickier unless seaborne hydrogen exports become economically viable.

Securing markets and a regional strategy are key

The low cost of land, proximity to Europe and its availability of solar energy-rich areas could give North Africa a competitive edge over the EU's preferred future sources in Eastern Europe – but taking green hydrogen from isolated MoUs to production and exports at scale is unlikely without a regional strategy to meet future EU demand. Political and economic realities across North Africa suggest that there is only a slim chance that it will become a green hydrogen hub this decade.

Political realities may be less of a hurdle in Southern Africa, but finding markets that could justify a rapid scaling-up of production is likely to be more challenging if export markets prove hard to access.