Pandemic quickens diversification of supply chains beyond China

by Dr Kaho Yu,

Co-authored with Wood Mackenzie's Min Li, Senior Consultant, Metallurgical coal

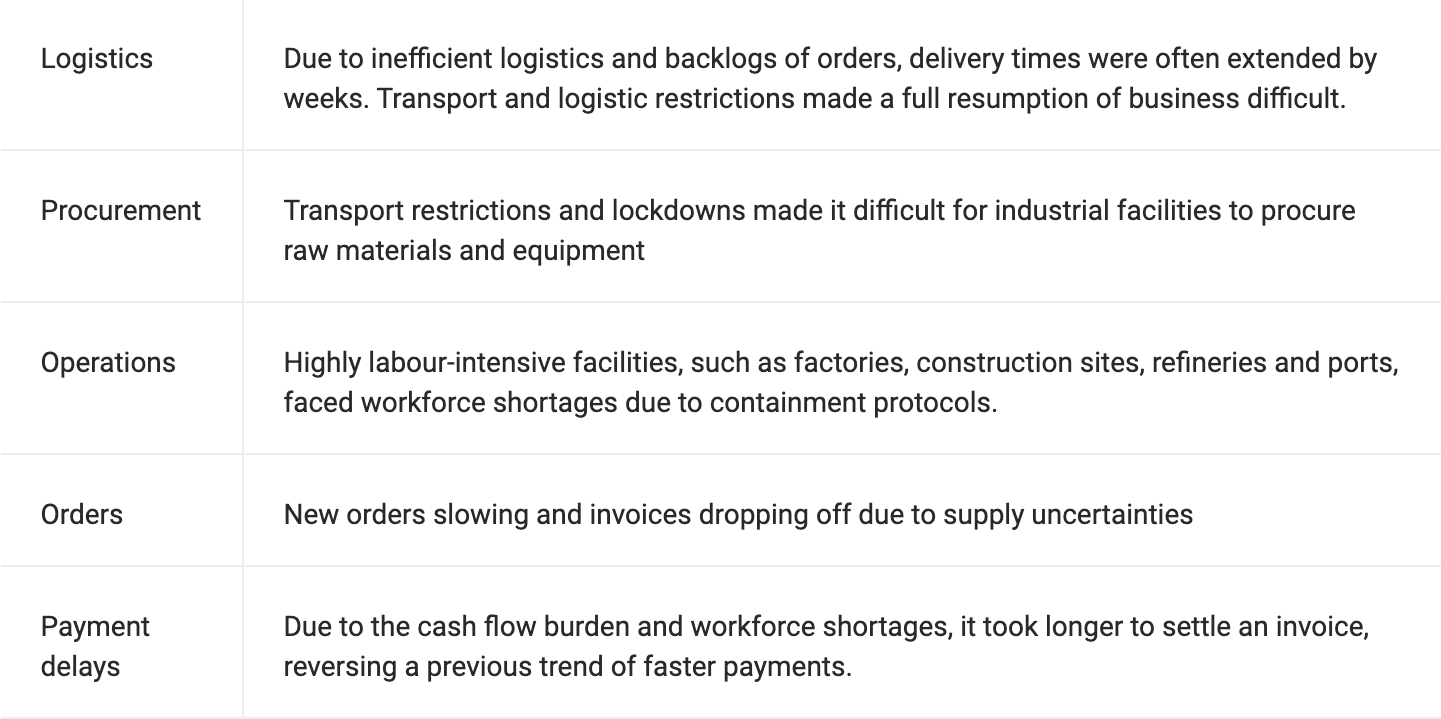

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit global trade and supply chains at an unprecedented speed and scale. Business first faced a supply shock, then a demand shock due to containment measures. The pandemic has particularly exposed the vulnerabilities of global supply chains (see Table 1) built on lean manufacturing principles and reliance on China – the world factory. The growing need for a “de-risking” strategy, namely geographical diversification and vertical integration, has become one of the main lessons of the pandemic crisis.

Companies over-reliant on China may decentralise and vertically integrate

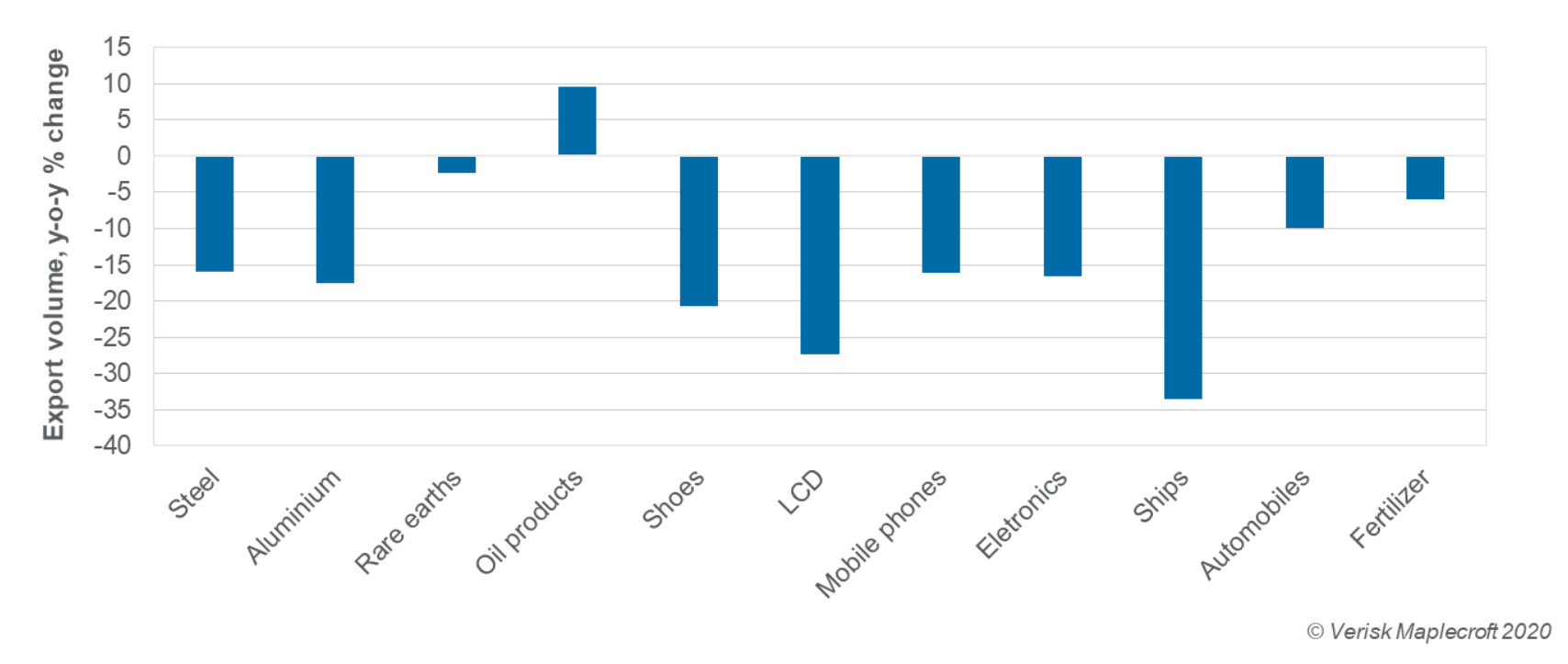

The rapid and profound impact of China’s lockdown in 2020-Q1 highlighted the problem with inflexibility in the global supply chain. Most of the affected Chinese regions are the manufacturing hubs of both raw and intermediate products, such as auto parts, hi-tech components and steel. Disruption of air travel and delayed production largely impacted companies that lack flexibility in their supplier base, but require quick delivery from China (see Figure 1). During the lockdown, these companies struggled to compete for alternative suppliers, and some were even forced to reduce or stop production.

But during 2020-Q2, the supply-side shock transformed into one of demand. Since many of China’s trading partners remain in lockdown, global orders are flatlining. Although Beijing has rolled out a stimulus package and reopened factories, China continues to feel the pressure of the global slowdown, with consumers spending less than before. It is doubtful whether the Chinese manufacturing sector can orchestrate a recovery purely on its terms. Multinational companies are facing a challenging choice between self-preservation and supplier solvency.

Together with increasing labour costs and trade regulations, supply vulnerability during COVID-19 has accelerated company efforts to diversify their supply chains outside China. We expect countries with lower operational costs such as Vietnam, Thailand, India and Mexico to be the key beneficiaries. Some larger corporates will also further vertically integrate throughout the value chain outside China, in order to secure more control over raw material prices, quality and supplies. Another expected trend is the decentralisation of manufacturing capacity, with companies looking to bring production home and rely on automation and small batch production to reduce cost.

No mad rush out of China but structural change is needed

The increasing need for supply chain diversification does not necessarily mean relocating the entire business outside China at once. Instead, it is more about adopting a “China plus one” strategy to structurally reduce over-reliance on China and to move part of the supply chain outside of the country.

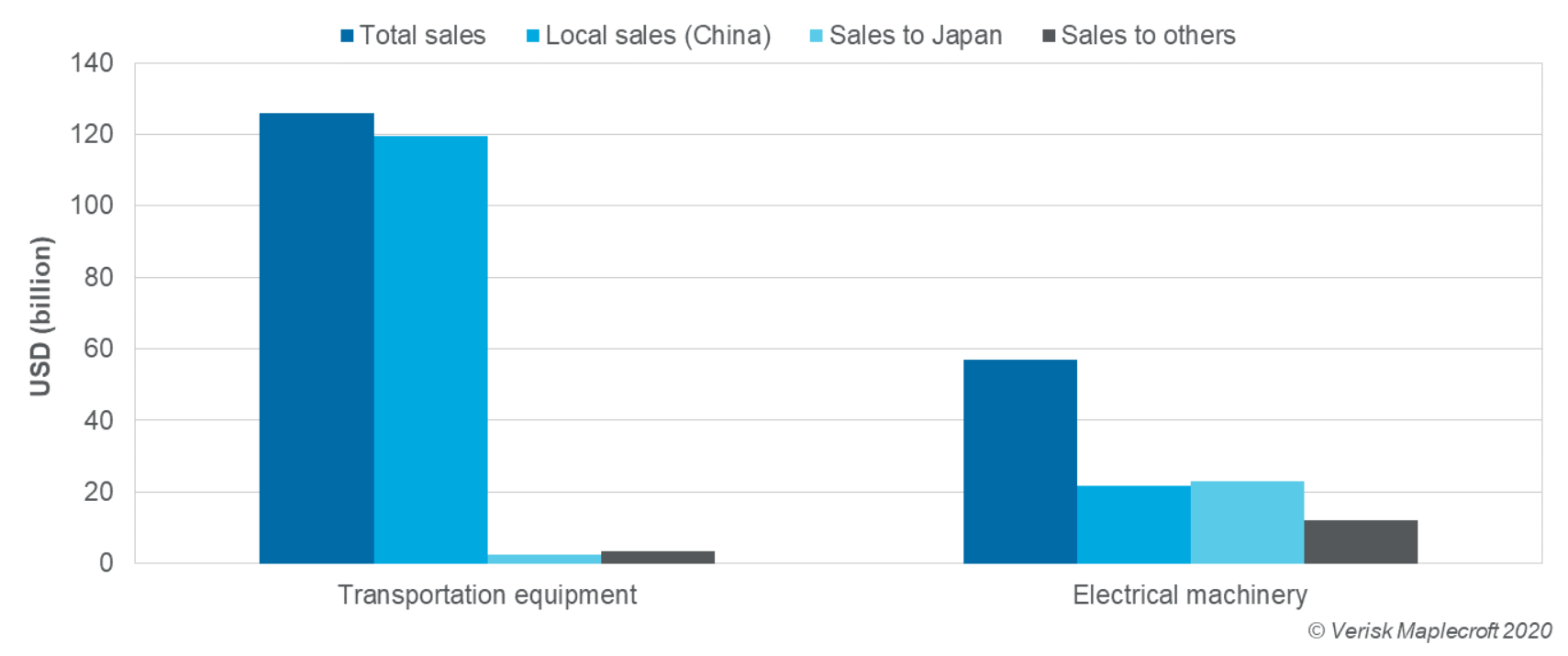

Foreign manufacturers – for example, Japanese automotive and machinery subsidiaries – were among the most affected during the lockdown in China. However, we expect that many of these manufacturers can only partially relocate their business outside China because most are “in China for China”. For example, Japanese automakers in China mainly manufacture for Chinese domestic buyers (see Figure 2). We expect them to remain in the country as they are prioritising “just-in-time” production and proximity to the consumers. In contrast, more OEM auto parts and electrical machinery produced in China are shipped to Japan, demonstrating more flexibility for supply chain diversification.

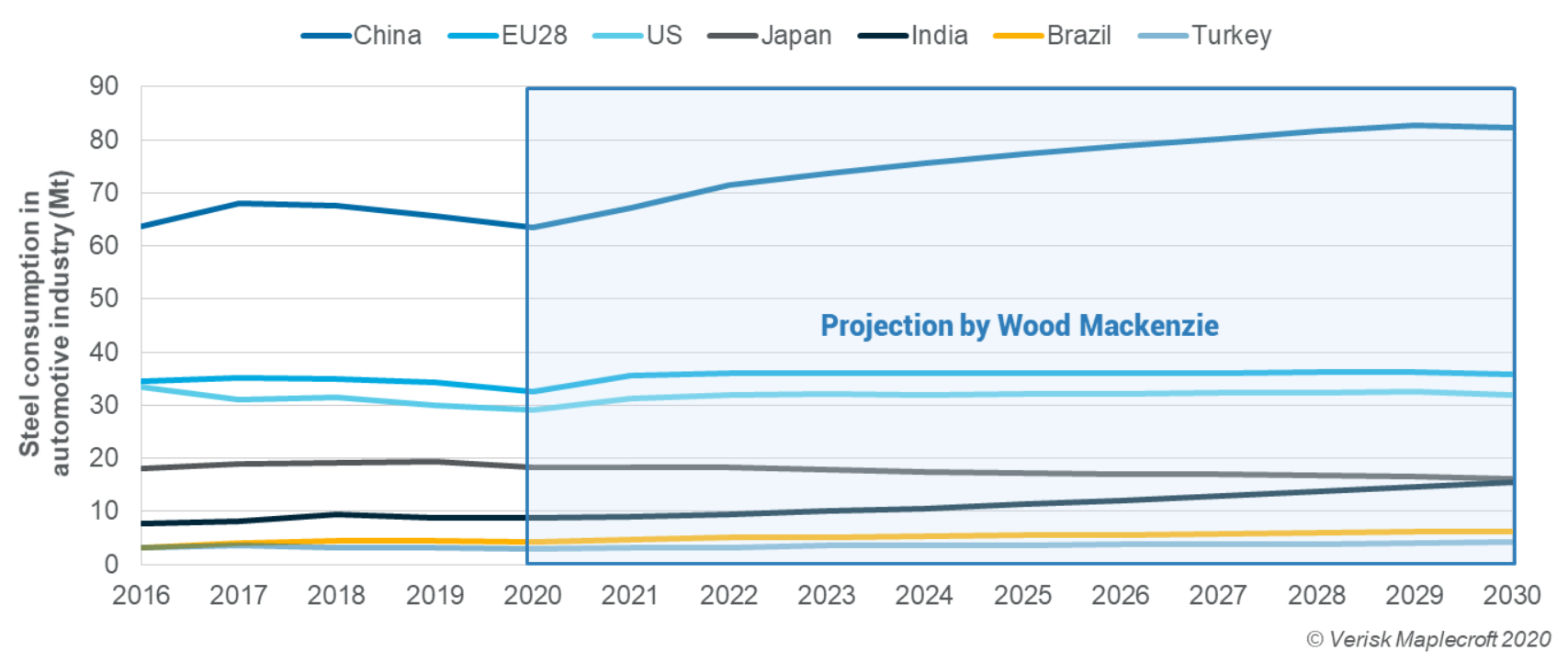

Therefore, we do not expect a mad rush out of China, despite a partial diversification of supply chains. In the long run, the country will remain a key production base for domestic consumers. This is in line with Wood Mackenzie’s steel consumption projection across varies Chinese sectors, in particular the automotive industry (see Figure 3).

To where should businesses relocate?

The growing trend of supply chain diversification has incentivised governments to provide preferential policies to attract business as part of their post-COVID-19 recovery plan. For example, while the US and Japan are willing to provide financial assistance to firms to relocate out of China, Vietnam has been rolling out preferential tax and land policies to attract foreign investors.

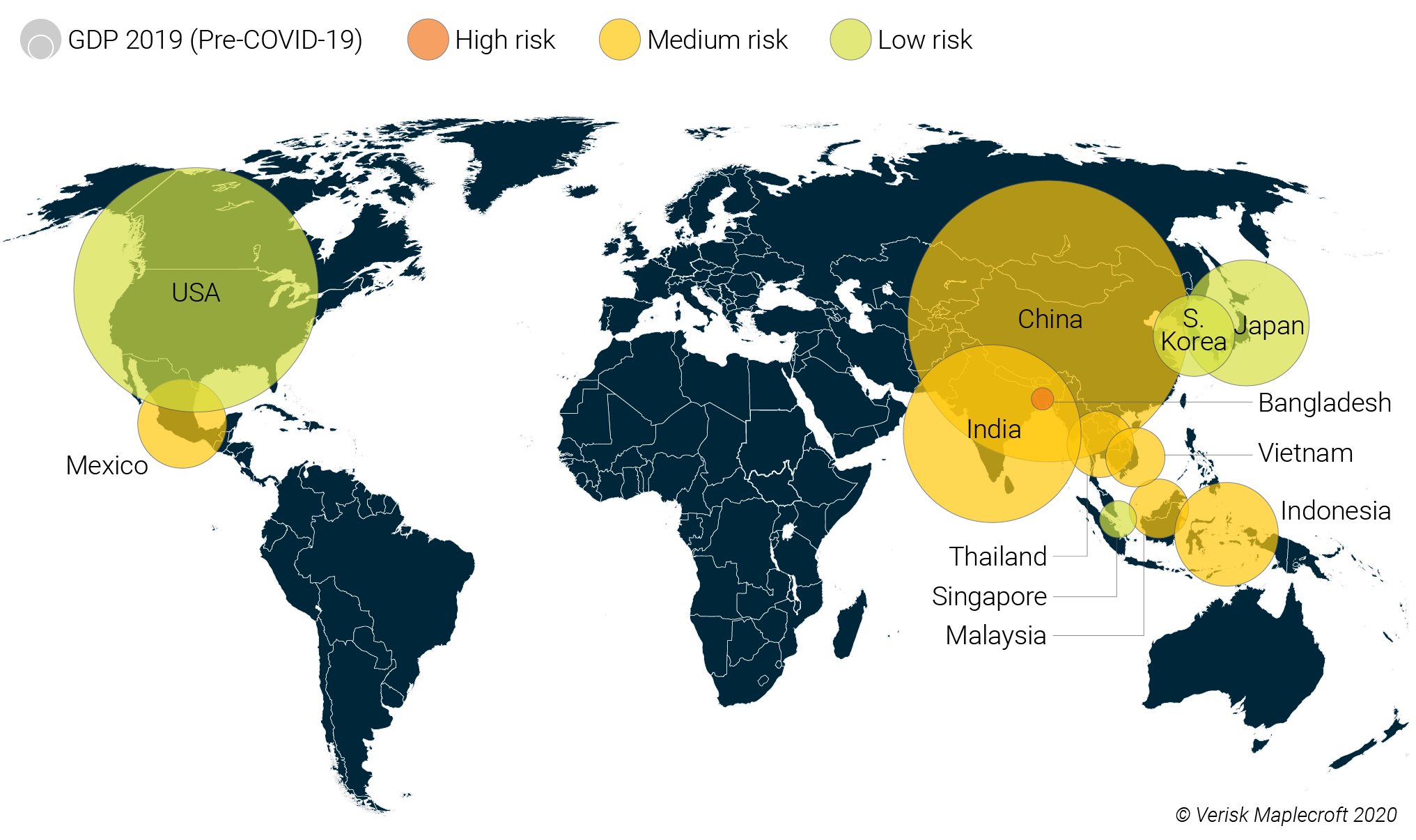

Beyond emergency stimulus packages, there are structural factors that determine the resilience of a country to recover or “bounce back” from COVID-19 in the medium to long term. It is crucial for any business with a diversification plan to evaluate the post-COVID-19 recovery prospects of alternative production bases. Our Recovery Capacity Index uses a five-pillar framework to assess the ability of countries to bounce back after the pandemic. Using this index, we have evaluated and compared 11 countries (see Figure 4).

The index categorises China as medium risk, ranked 76th in the world. Thanks to its robust institutions, China’s overall score is marginally better than that of some developing countries. Yet, its performance on compounding factors is among the worst 20 countries. These factors, including civil unrest and trade tensions will continue to undermine its long term recovery prospects. Developed countries such as the US, Japan and Singapore have a better recovery capacity but are not ideal choices for diversification plans due to high operational costs. Comparatively, countries like India, Mexico, Vietnam and Thailand are more feasible post-COVID-19 options.

Supply chains cannot be established overnight, and companies still have to overcome the expensive and time-costly process of relocation. Yet, one lesson from COVID-19 is that the performance of many multinational companies is highly weighted towards the level of exposure to China’s supply chain. There will be an increasing need for a diversification strategy that takes post-COVID-19 recovery capacity into account.