Pandemic crisis deepens global divisions on climate action

by Franca Wolf,

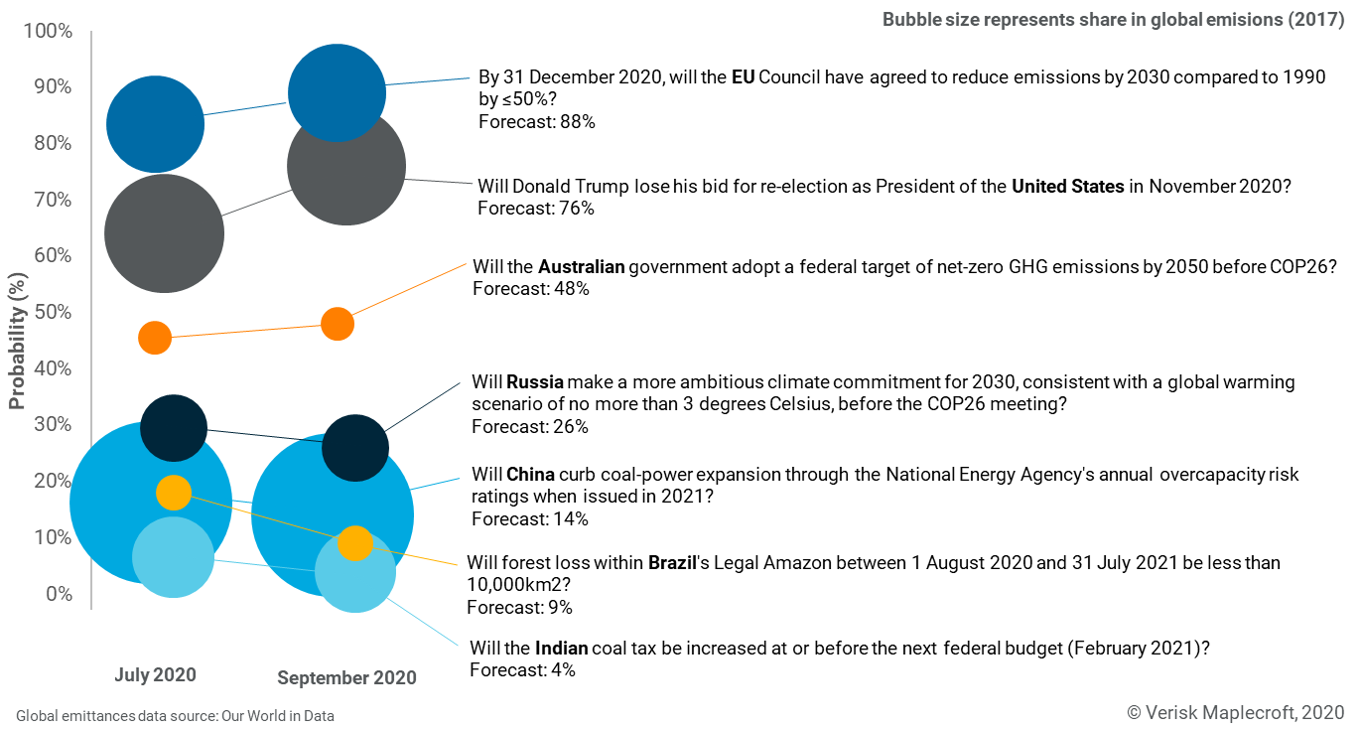

As the pandemic keeps a tight grip on nearly all countries, the gap between the world’s major emitters on their response to the crisis has also deepened. We have become more certain in our assessment that the EU and US will advance their energy transition, while we have raised the likelihood that emerging markets will, conversely, prioritise any economic recovery over a green economic recovery (see visual below).

Developed countries: climate inaction as electoral liability

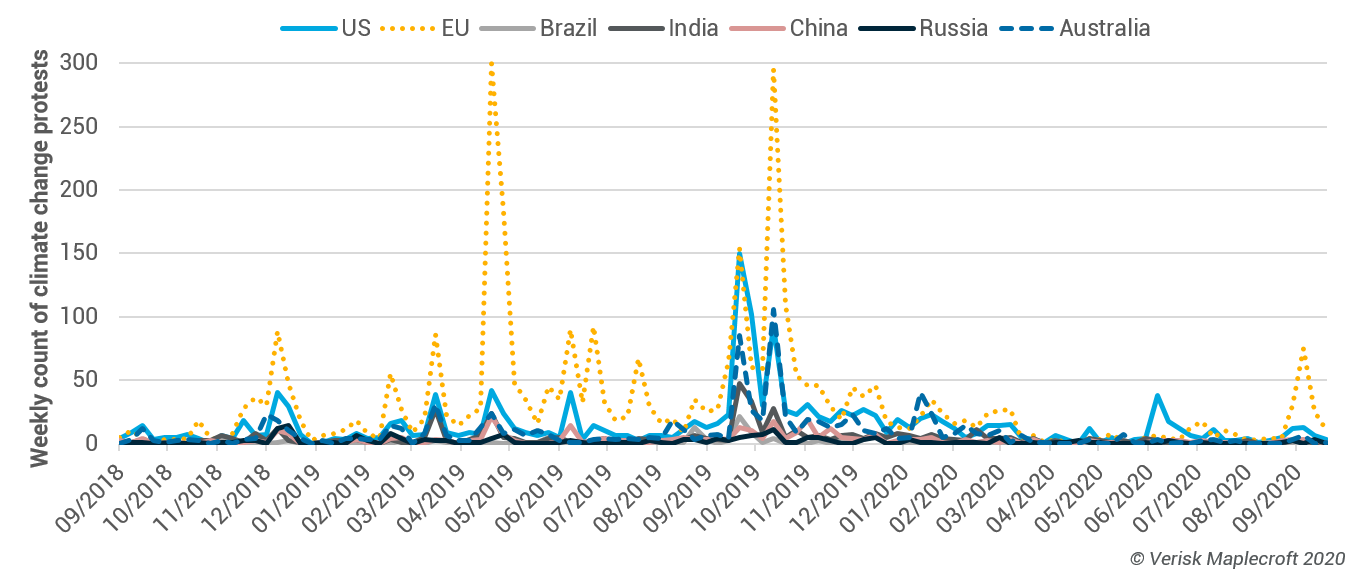

The pandemic has exacerbated long-running fault lines between developed and emerging markets on climate action. A key differentiator is the public demand for governments to act on climate change. Our data on the frequency of climate protests in the seven major emitters of our forecast series highlights the varying significance of climate change as a public concern (see visual below).

Since late 2018, the EU has by far registered the highest count of climate protests among the seven emitters, demonstrating a strong public demand for increased climate action. Moreover, the electoral success of Green parties in major EU economies highlights that climate inaction has become a political liability. Consequently, we have raised the likelihood to 87% for the third-largest emitting actor to raise its 2030 emissions reduction target on the pathway to 2050 carbon neutrality.

Meanwhile, we now forecast a 76% likelihood that Democratic candidate Joe Biden will beat US President Trump in November’s election. With Biden having likewise pledged to make the US carbon-neutral by 2050, this would see the US advance its energy transition – also as a result of a growing public demand for climate action.

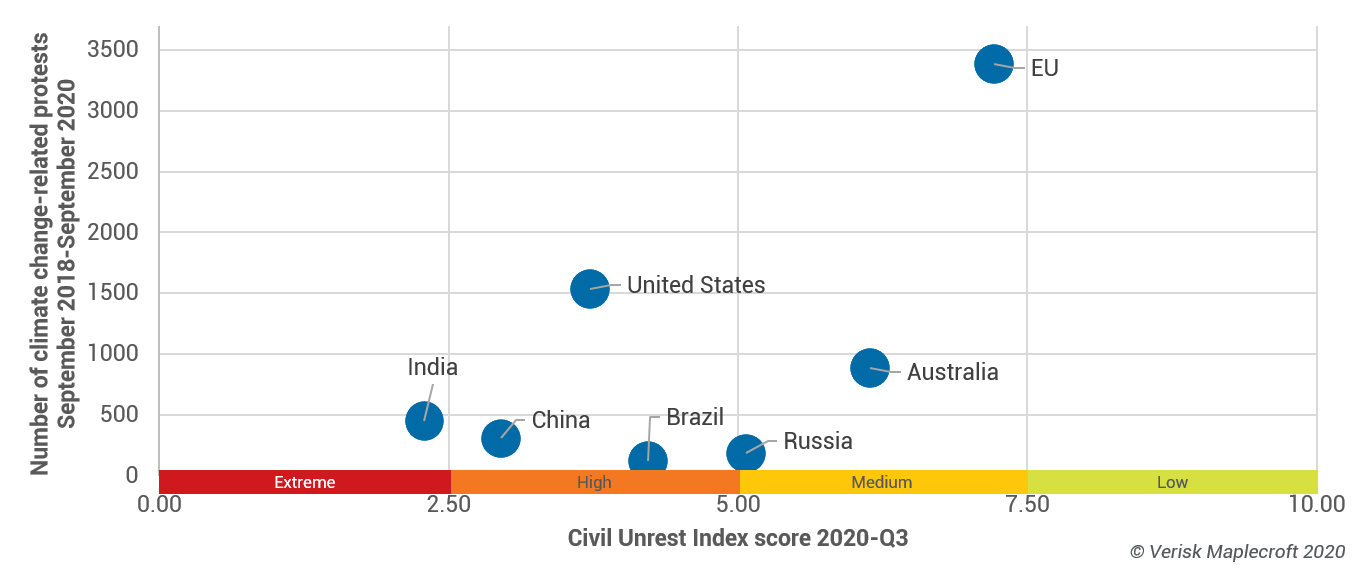

Emerging markets: climate change as one protest driver among many

In contrast, climate action has often been overshadowed by other economic issues in emerging markets. Although India, China, Russia and Brazil record only a low number of climate change-related protests, they score in the high- or extreme-risk category in the Civil Unrest Index, highlighting that unlike the EU, issues other than climate change are driving social discontent (see visual below).

Russia provides an instructive counterpoint to the EU. The pandemic has exacerbated stagnating Russian economic growth and falling living standards have driven civil unrest. In turn, the low number of climate protests highlights limited public concern with climate action. While Russia is experiencing negative impacts from climate change, it lacks a robust civil society that can turn localised fears into concerted public pressure. This contributes to an only 26% likelihood of the Kremlin significantly raising Russia’ 2030 climate commitment before COP26.

China has recently committed to a 2060 net-neutrality target. However, the softer target, compared to the EU's and Biden's 2050 date, and a lack of detail drive concerns that the move is more about placating an international audience than robust climate action. We forecast only a remote likelihood that Beijing will curb coal-fired power expansion in the short term, as it doubles down on coal to spur an economic recovery.

Australia is an outlier in the developed-emerging market dichotomy. Canberra remains unlikely to adopt a 2050 net-zero target, but the forecast has increased marginally to 48% from 45% in July. This represents a high degree of uncertainty, but once again public pressure is a central factor deciding the government’s commitment to climate action. The October Queensland election and the impact of the next wildfire season on public sentiment are key signposts for the Coalition government considering its pro-coal stance.

Global impact of national climate action

The EU appears to be willing to strengthen its own climate mitigation framework without waiting for reciprocal action from other major emitters, but its actions will impact others. Raising the 2030 emissions reduction target will only be a first step, as the EU Commission will propose further initiatives in summer 2021, potentially including a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

Find out more about Climate change and environment

The specific design will only become clearer as we approach the instrument’s proposal. Yet, by seeking to ensure that EU producers are not disadvantaged by the EU Emissions Trading System’s (ETS) carbon price vis-à-vis non-EU producers, the latter will likely face a monetary burden linked to the carbon content of their products.

We can expect fierce lobbying around the EU Commission’s CBAM proposal. The US, China and Russia have already criticised plans to introduce a CBAM and are more likely to fight the initiative than introduce corresponding carbon pricing initiatives that would shift the carbon pricing revenue from the EU to their own coffers.

What is the conclusion?

Public demands for climate action are a key factor to watch in predicting governments’ commitment to the energy transition. Among the world’s seven major emitters, we forecast emerging markets China, Brazil, Russia and India to continue prioritising economic recovery over climate action, as economic concerns outweigh calls for decarbonisation.

In turn, a strong climate protest movement has been a driver behind our expectation that the EU will raise its climate commitments this year – and follow with new regulations in 2021. Yet, just as pollution leads to climate change impacts beyond the polluters’ borders, EU climate action such as the potential introduction of a CBAM would have implications for business globally.