New Xinjiang ban will upend multiple sectors

by Sofia Nazalya,

In January 2021, the UK and US both escalated pressure against the Chinese government in retaliation for human rights violations in Xinjiang. With ramped-up measures against forced labour in the region, companies with operations in Xinjiang are now faced with ever increasing reputational, financial and operational risks. As international condemnation of abuses in Xinjiang reaches a boiling point, it is looking increasingly likely that companies operating in Xinjiang face the prospect of a total exit from the region.

Ramped up measures, but UK response remains comparably weak

The latest Withold Release Order (WRO) by the US against cotton, tomatoes and related downstream products is the most sweeping US import ban against China to date. Since the first import ban against Chinese goods began in 1991, WROs have consistently targeted specific manufacturers rather than an entire region. In this respect, the latest WRO signals an escalation in efforts by Washington to pressure Beijing on human rights in Xinjiang.

Although the UK has certainly struck a stronger tone against China on Xinjiang abuses in recent weeks, actual measures put forward are comparably much weaker than that those taken by the US. The most significant move is the announced strengthening of the UK Modern Slavery Act by introducing financial penalties for companies. Adding fines will give teeth to the law, which has long been criticised as weak due to the lack of sanctions against non-compliant companies.

However, any major improvements to the law are unlikely in the next two years, despite growing calls by human rights groups for more forceful measures against Beijing. The recent defeat of an amendment on a trade bill in the House of Commons that would have given British courts the power to determine whether genocide is being carried out in Xinjiang is a case in point. While voices across all parties have called for stronger measures against China, we expect that the UK government will continue to drag its feet, with trade and business interests likely to be a major driver.

Learn about our Commodity Risk Service

US Withold Release Order a precursor to total Xinjiang ban

The US import ban on cotton and tomato products manufactured in Xinjiang has wide-ranging implications for apparel and food producers. The WRO’s regional scope creates a presumption that all cotton and tomato products are associated with forced labour, unless proven otherwise. However, US Customs requires a high evidentiary standard which is challenging to meet. While the WRO does not bestow financial penalties onto non-compliant companies, it essentially establishes barriers that highly discourage companies from sourcing cotton or tomato products from Xinjiang. The reputational backlash of being perceived to benefit from goods manufactured in Xinjiang alone would likely cost companies dearly, with the possibility of consumer boycotts and shareholder pressure.

In other words, the WRO effectively sounds a death knell for importing cotton, tomatoes and related downstream products to the US, increasing pressure on companies to seek alternative suppliers. Uprooting suppliers and shifting operations will be a massive disruptor for businesses. However, given that this is not the first US measure against Xinjiang operations, most companies likely already have, or are in the process of creating, contingency plans.

Despite weak measures, UK companies likely to relocate voluntarily

While it is not yet clear how extensive financial penalties will be under a strengthened UK Modern Slavery Act, Raab’s statements indicate that fines will likely be sufficiently high to deter companies who flout transparency requirements. Irrespective of how large fines will be in the final version, the rapidly turning international tide against Xinjiang products is likely to encourage British companies to re-examine their operations in the region well before the change. With the UK government issuing new due diligence guidance to businesses, we expect that ultimately, the difficulties of conducting reliable audits will likely see textile and food operators gradually making an exit from Xinjiang.

Complete disassociation from Xinjiang will be challenging

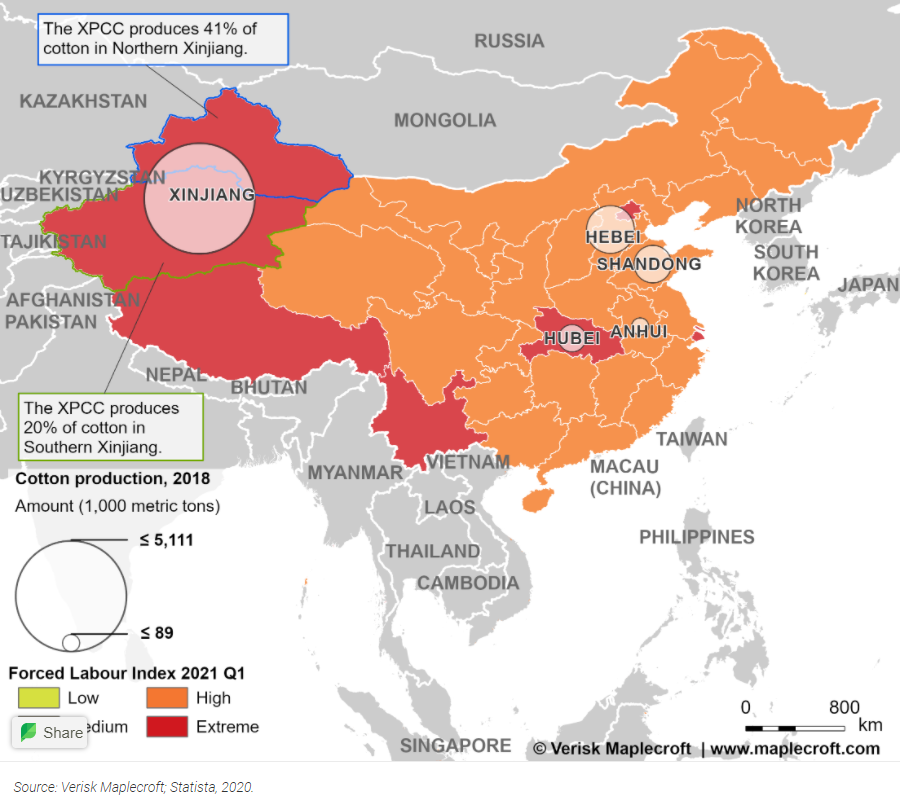

However, where international companies will relocate to is still an open question. But even if companies seek suppliers elsewhere in China, high or extreme forced labour risks will still be an issue (see visual above). Our subnational Forced Labour Index 2021-Q1 shows that, although Xinjiang records some of the highest levels of forced labour risk in country, the situation remains dire elsewhere. In addition, a recent report by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies found that the Chinese government has transferred at least 80,000 Uyghur forced labourers to work in factories in other regions. This further complicates matters as it will make it even more challenging to trace forced labour originating from Xinjiang in supply chains.

As we have mentioned previously, reducing reliance on the Chinese supply chain is challenging, given that China accounts for 50% of global exports of woven cotton fabric. Even if businesses source from outside of China, proving that their textile supply chains are completely rid of Xinjiang cotton will be a demanding task. The ability to account for all sourced products and labour sources is fundamental to successful due diligence. Currently, this is more an aspiration than reality, and will require enhanced methods of monitoring and verification.

Read more about conducting human rights due diligence

Other sectors likely to be targeted

The implementation of the WRO in the US expedites a core element of the proposed Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act – the prohibition of certain imports from Xinjiang that are made with forced labour. In our view, it is only a matter of time before the Act is passed – likely sometime this year – which will then go a step further by making it policy to assume that all labour in Xinjiang, or associated with Xinjiang’s “poverty alleviation” or “mutual pairing assistance” programmes constitutes forced labour.

As Xinjiang is also a major producer of coal, chemicals, sugar and polysilicon, these supply chains will likely be most vulnerable to disruption. If the Act is passed in its current form, it extends the presumption of forced labour from cotton and tomato products to virtually all sectors, making any form of business in Xinjiang too fraught with legal and operational risks for it to be practical.