Despite rising perceptions that Russia is extending its geopolitical reach, the foundations of Moscow’s claim to renewed global influence are shaky at best. Moscow spent much of 2019 trumpeting diplomatic re-engagement with Africa, piggy-backing on the spread of Russian private military contractors (PMCs) – particularly the infamous Wagner group – across the continent.

With its domestic economy stagnating and protests growing, the Kremlin wants to burnish Russia’s credentials as a global power. However, the reliance on PMCs and non-state actors to underpin Russian power projection means these efforts are driven more by commercial than political logic – in other words, the tail is wagging the dog.

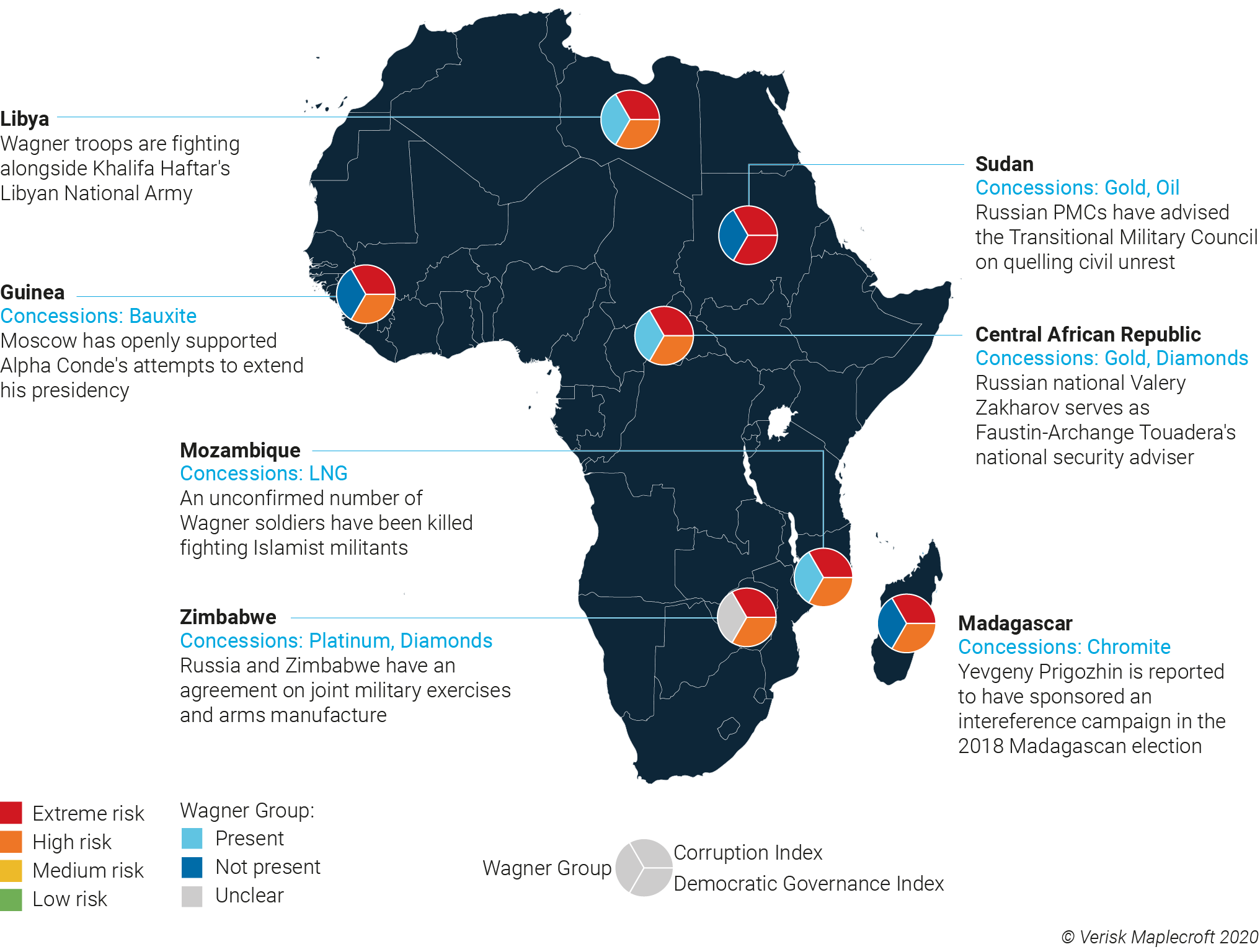

African state clients have tended to pay for Russian support through shares in mines and natural resource deposits, with PMCs providing the logistics and security needed for commercialisation. This means deployments have generally focused on states with weak democratic and legal norms and, in some cases, where the government’s hold on power is tenuous.

Register for our Political Risk Outlook 2020 webinar

PMCs can provide a veneer of stability, but their capabilities are too limited to provide a foundation for more permanent Russian influence. Russia’s attempts to provide political and campaigning support have generally backfired due to lack of local knowledge. This creates a scenario in which Russian claims to a host of resources, many vital for the production of electric batteries and other next-generation technologies, are dependent on the good will of governments that Moscow is ill-equipped to maintain in power.

Commercial opportunism, not strategy, guiding Africa policy

It is financial gain that is driving Russia’s newfound foreign policy assertiveness in Africa. Russian companies – including major established miners and secretive offshore holding companies (many of which are linked to Yevgeny Prigozhin, the alleged founder of Wagner) – are increasingly gaining control of mineral rights and concessions in exchange for ‘services’ rendered.

As Figure 1 illustrates, Russia’s preferred partner states in Africa are characterised by weak democratic governance and all are in the extreme risk category in our Corruption Risk Index. These factors make it easier for host governments to sign over these rights with minimal oversight.

The use of PMCs and other private sector resources, such as political ‘technologists’, minimises the resources Russia must expend to financially benefit from these arrangements. Utilising deniable mercenary troops also means that when contractors die in combat – as an unconfirmed number of Wagner soldiers did in Mozambique in October 2019 – the Kremlin does not take a political hit.

When Russia has attempted to operate in more stable locations – usually by conducting electoral interference on behalf of favoured candidates – the results have been less successful. A case in point is Madagascar, where Russia was obliged to switch candidate mid-campaign when it became clear that its first choice would finish a distant third in first-round polling.

What is the market impact?

Guinea is an example of the potential downside for Russia if local allies fail. Prompted by Guinea’s importance as a supplier of bauxite for Russian aluminium producer Rusal, Russian diplomats in the capital, Conakry, have openly supported President Alpha Condé’s efforts to extend his term in office; this has helped fuel months of increasingly bloody civil unrest.

Presidential and legislative elections in Guinea are due in 2020, and China is also competing with Russia for access to its bauxite and iron ore deposits. A scenario could arise where a new leadership could challenge or reverse mineral deals agreed by President Condé. At that point, who ‘owns’ Guinean bauxite or iron ore becomes a matter of dispute once it hits world markets.

Download the Political Risk Outlook 2020

This presents a substantial risk to ensuring the integrity and sustainability of supply chains across the region, as well as compliance with sanctions (Prigozhin and his business interests have been subject to extensive US sanctions). While Russia’s renewed presence in Africa is causing concern in many Western states, the real problems may only present themselves with changes in a country’s leadership.

What if… Russia’s client governments collapse?

It is not just in Africa where Russia’s commercial interests may be difficult to enforce when facts on the ground change; the claims themselves can be used as a bargaining chip. In Venezuela, Rosneft has provided billions in loans to the oil and gas sector, with equity stakes serving as collateral. In the event of regime change in Caracas, and a successor government supported by the West takes power, Moscow can use these debts as bargaining chips to secure a seat at the table during the transition and ensure Russian interests are taken into account.

In Venezuela, Russia has a larger footprint, greater local knowledge and economic commitment. If Russian PMCs are driven out of Sudan or Central African Republic, the Kremlin may have a tougher time gaining a seat at the negotiating table. But that doesn’t mean that Russia will cut its losses – instead, Moscow is likely to continue pushing its claims and enlist allies in doing so.

This opens a scenario in which the legal owner of a particular ingot of bauxite or nickel is a matter of international dispute. As the transition towards renewable energy continues apace, demand and competition for African minerals is set to intensify. If ownership disputes become a part of that competition, ensuring the integrity of supply chains in advanced manufacturing will become exponentially more difficult.