LkSG supply chain law presents German companies with environmental challenges close to home

by Jess Middleton,

Germany highest risk globally for environmental harms laid out in LkSG

German companies are the most exposed globally to a host of environmental risks that larger businesses are now obligated to report on under Berlin’s new Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, the ‘LkSG’, according to our latest data.

The law, which came into effect in January, will fundamentally change the way organisations identify, manage and disclose waste, pollution and human rights harms in their supply chains – those that do not will face a range of punitive measures.

Our newly released LkSG Risk Analysis Dataset helps companies analyse all LkSG risks across their global operations and supply chains. It features 25 indices mapping the entire range of human rights and environmental risks defined in the law from country, sector and raw material-specific perspectives. These include child labour, forced labour and water stress, as well as appropriate context-dependent factors, such as conflict and civil unrest, freedom of expression and indigenous peoples’ rights.

The data shows that Germany ranks among the 10 highest risk countries for Mercury Pollution, Hazardous Waste and Persistent Organic Pollutants – the three environmental factors referenced in the law, for which we have created bespoke risk indices.

The findings suggest that the LkSG’s consolidation of human rights and environmental concerns – part of a broader push to recognise the universal right to a healthy environment – could create new, possibly unforeseen, domestic regulatory challenges for companies, many of whom are already contending with upticks in civil and labour rights risks across major sourcing countries.

“The LkSG marks a paradigm shift in the regulatory landscape governing supply chain due diligence, which has typically centred on social risks associated with sourcing from the Global South,” says Dr James Sinclair, our Director of Human Rights. “Major polluting countries in the Global North will now find themselves under the legal microscope, including Germany itself.”

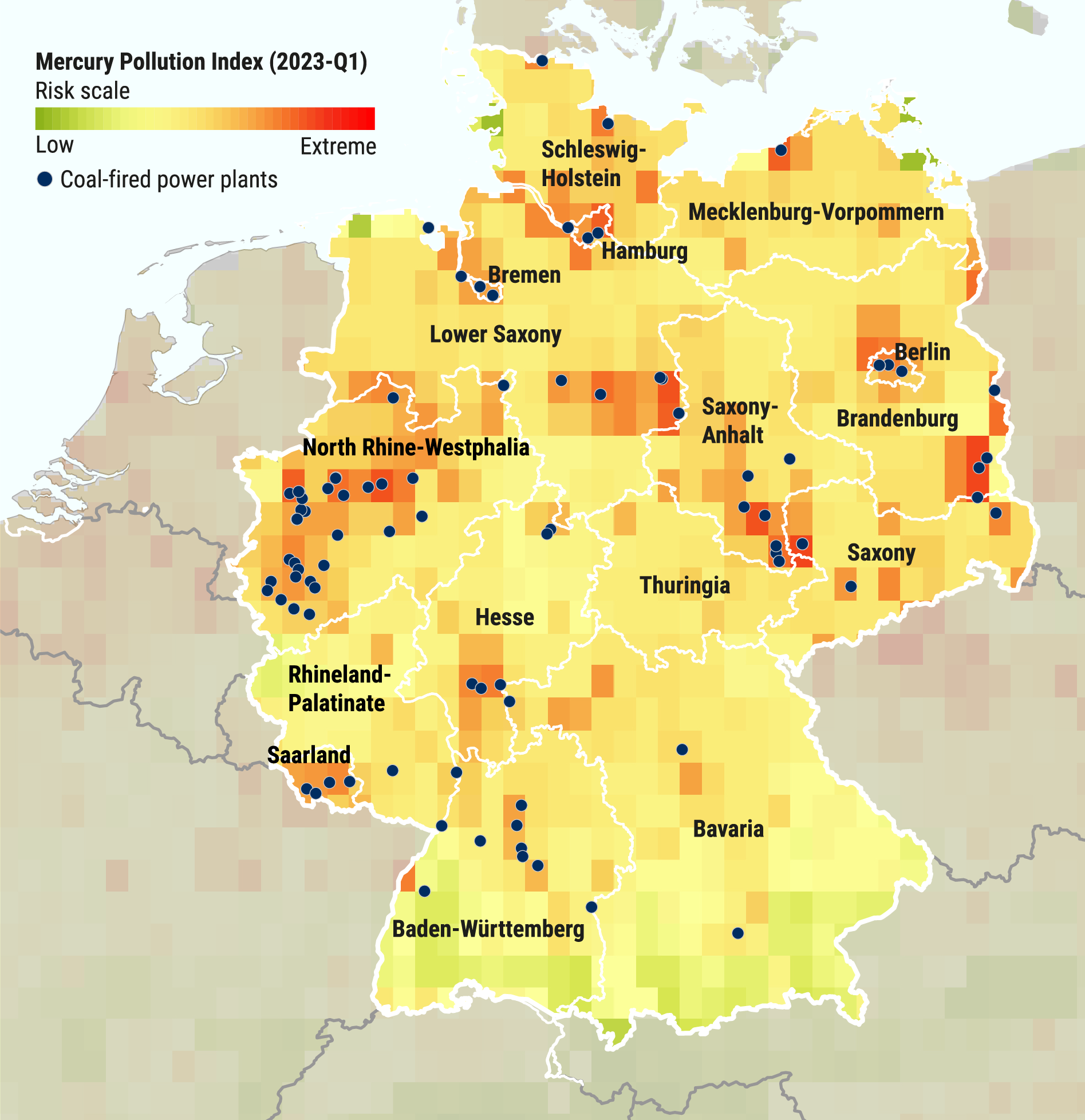

Mercury pollution a major concern in Germany’s industrial areas

Our subnational Mercury Pollution Index assesses the amount of mercury depositions and emissions in a given environment. Focusing on the 50 top commodity producing countries globally shows that Germany ranks 3rd highest risk in the dataset, behind only the Czech Republic and South Korea, despite its full ratification of the Minamata Convention on Mercury.

This is primarily a result of the burning of coal: the fossil fuel still makes up 18% of Germany’s total energy supply, despite accounting for 70% of the country’s mercury emissions. This means that larger companies using power from German energy suppliers burning coal could fall foul of the LkSG’s risk management requirements, and also face tough scrutiny related to their scope 2 emissions.

The German government had plans to phase out coal by 2030 in favour of cleaner alternatives, but these were shelved in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Several German coal-fired power plants have since been reactivated as part of the country’s push to reduce its dependence on Russian energy.

Unsurprisingly, these risks are most pronounced in areas associated with heavy industry (see Figure 1). Indeed, beyond the city states of Hamburg, Bremen and Berlin, our subnational data flags Saarland and North Rhine-Westphalia – both situated in the industrial Rhineland – as the two highest risk German federal states.

Germany performs similarly poorly on our Persistent Organic Pollutants Index, where it ranks 2nd highest risk globally, and the Hazardous Waste Index, where it ranks 7th highest risk for the generation of toxic, infectious and/or radioactive properties.

Environmental and social risks collide in world’s key sourcing hubs

German-owned companies are far from the only organisations facing a complex global challenge in complying with the LkSG. Thousands of firms worldwide will eventually fall within scope of the law, which encompasses the operations and supply chains of larger businesses registered in Germany, including branches of foreign companies.

When conducting their LkSG risk analysis, these companies must also consider ‘context-dependent factors’, including political framework conditions and the presence of potentially vulnerable groups of people.

To better illustrate what this means in practice, we mapped our Mercury Pollution Index against our Migrant Workers Index. Doing so brings a host of major Asian sourcing hubs into view.

The risky top right of Figure 2 shows countries where companies are most exposed to a combination of mercury pollution and social risks, whereby vulnerable groups may be more likely to bear the brunt of any damage dealt to the local environment. Indeed, various studies have linked severe health issues such as nerve damage and even certain cancers to mercury pollution, with pregnant women, young children and babies especially vulnerable.

These countries include China, India and Bangladesh – adding to a trend whereby companies with global supply chains are increasingly exposed to escalating human rights risks, including modern slavery and child labour, in the world’s major manufacturing locations.

Comprehensive risk data key in new era of supply chain regulation

The LkSG might be the first supply chain due diligence law to explicitly link environmental actions to human rights harms, but it is unlikely to be the last. The EU’s upcoming Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDD) is also seeking to bridge the gap between social and environmental risks, and could include factors beyond the current scope of the LkSG, such as biodiversity loss, deforestation and damage to marine environments.

“As the universal right to a healthy environment becomes increasingly baked into regulation, companies with access to robust, comparable human rights and environmental risk data will find themselves in the best position to effectively identify, prioritise and address salient issues,” adds Sinclair. “From social risks in Asian sourcing hubs to environmental hazards in Western Europe across both their own operations and supply chains, the scale of the task at hand is enormous.”