Latin America spearheads global shift towards resource nationalism

Download our Latin America Resource Nationalism Index 2021 map

by Jimena Blanco and Mariano Machado,

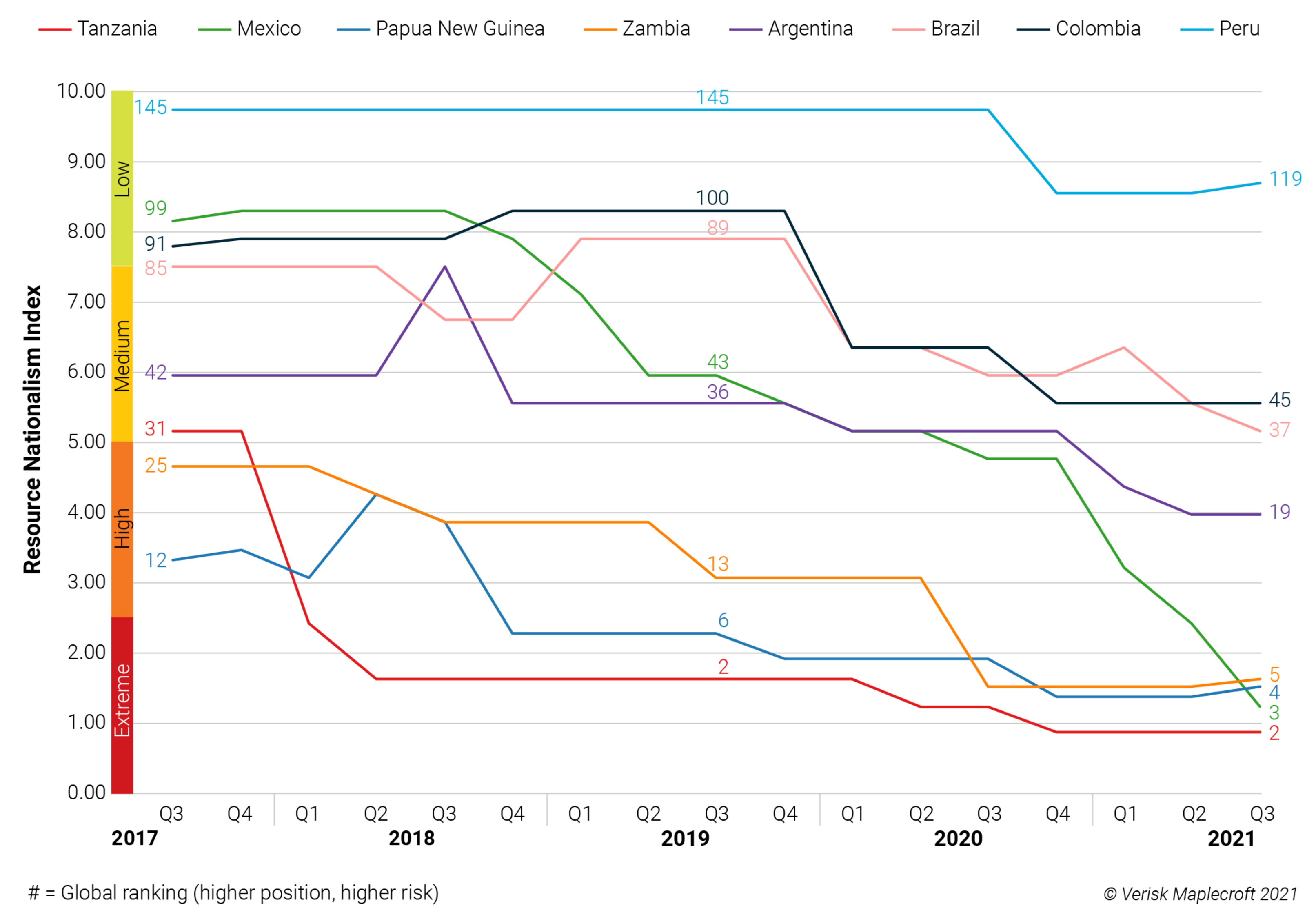

In the two-and-a-half years since President López Obrador (AMLO) came to power, Mexico has dropped 85 places in our Resource Nationalism Index (RNI) to become the third highest risk location for the issue globally, with only Venezuela and Tanzania scoring worse. This echoes a sustained move by a swathe of countries to ensure they take greater control of the revenues generated by the minerals and hydrocarbons produced within their borders.

Since 2017, our data reveals that natural resource companies in 66 countries have witnessed negative shifts in the risk environment. These range from increasingly rare cases of direct expropriation, to tax and royalty increases, and demands for companies to use locally produced goods and services, which are gaining ground as preferred forms of intervention. According to the index, motivations for resource nationalism differ widely between countries. While these include the legitimate renegotiation of contract terms and traditional drivers, such as fiscal pressures, political ideology, and populism, the research shows that local community and environmental concerns are playing a bigger role in influencing policy shifts.

Mexico stands out as seeing the largest increase in risk out of the 198 countries assessed by the RNI, driven by AMLO’s nationalist agenda that wields community and environmental arguments as justification for greater state involvement in the extractive sector. Worryingly for miners and energy firms, its performance is indicative of a wider regional trend. South America’s three largest economies, Brazil, Argentina and Colombia are also experiencing substantial negative shifts in the index, while the once stable mining destinations of Peru and Chile are on the cusp of political changes that will alter the operating environment for the industry.

Data reveals shift towards more extreme measures in more countries

With 51 countries decreasing in risk over the last four years, compared to 66 recording a significant increase in the risk of resource nationalism, the RNI shows a definite swing towards more interventionist policies in the natural resource sector. There is also an upward trend in the number of countries categorised as ‘extreme risk’ in the index, rising up from 5 in 2017-Q3 to 11 in 2021-Q3 – many of which are key natural resource producers.

- Venezuela

- Tanzania

- Mexico

- PNG

- Zambia

- Russia

- North Korea

- Kazakhstan

- DR Congo

- Zimbabwe

- Swaziland

The countries above constitute the extreme end of the resource nationalism spectrum, but the chart below shows the direction of travel. For investors in Latin America, it is worth noting that outside of Mexico, they need to closely track developments in Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, and Peru, which are among those that have witnessed the biggest rises in risk. For these locations, we expect this trend to worsen in the coming two years.

Resource nationalism taking main stage in Latin America

Breaking down the issues at a country level provides insight into the drivers of resource nationalism and the tools being deployed by Latin American governments as they attempt to wrestle more control over their resources.

Mexico’s nosedive in the Resource Nationalism Index can be explained by President López Obrador’s nationalist tendencies, which have driven rollbacks of major reforms, such as the 2015 energy restructure, and seen the executive actively infringe on the independence of regulatory bodies in the energy sector. A legislative proposal (now stalled) to nationalise lithium indicates AMLO’s interventionism is all but certain to expand beyond oil and gas in the second half of his term. This will be short of direct expropriations without compensation, but undue intrusion into autonomous agencies overseeing the mining sector and ideologically motivated regulatory shifts can be expected.

Fill in the form to download our Latin America Resource Nationalism Index 2021 map

In the case of Argentina (ranked 19th highest risk globally), the deterioration is driven by President Alberto Fernández's intervention across multiple sectors. These have ranged from the nationalisation of assets to the attempted takeover of private firms – including in agriculture and infrastructure – as well as economic measures like price caps – in oil and gas and telecoms – higher tariffs, increased fiscal withholdings and limits on the ability of investors to repatriate dividends. Because intervention has largely ideological and political motivations, we expect it to intensify as the government heads into the second half of its term, regardless of the outcome of the November midterms.

Brazil’s downgrade (from 85th to 37th in the index) does not have a clear driver, which arguably creates more uncertainty as to the future path of travel under President Bolsonaro. Indeed, he has regularly intervened in the country’s energy sector while proclaiming his actions were to ensure a free market. His falling support also risks an escalation in the use of populist measures, like interfering in petrol pricing by Petrobras, as he bids for re-election in 2022. More than a year out, the alternative appears to be a different but equally concerning form of populism in the potential return of former president Lula Da Silva.

With resource nationalism firmly back on the agenda for a host of governments in Latin America, the longterm regulatory outlook for mining and energy firms is more uncertain than at any time over recent years. Investors and extractive companies should buckle up.

Mariano Machado

Senior Americas Analyst

Chile and Peru set to open new front for miners

For the mining industry, nowhere are these factors more crucial than in Peru and Chile. Divisive elections mean the rest of 2021 could bring about sweeping changes in Latin America’s two most important mineral producers.

Peru, ranked 119th, remains in the ‘low risk’ category of the index for now. But the election of left-wing Pedro Castillo, arguably the first genuinely ‘campesino’ president, has produced a leader that actively flies the banner of rural communities in demanding that the mining sector delivers the development successive administrations have promised.

In Chile, the primaries for the upcoming general elections have confirmed that voters want new political leadership to take them through the constitutional reform process and the implementation of a new Magna Carta. The country, currently ranked 96th and low risk, provides a clear example of how sustainability-driven debates have been ‘weaponised’ since the outbreak of civil unrest in 2019-Q4, boosting the candidates with the stronger ‘outsider’ profile in the primaries of the two leading coalitions. As the constitutional convention drafts a new document, and new leadership takes office in 2022, debates over the mining sector’s fiscal contributions, and how to address growing social demands for stronger environmental protections will begin to shape the future for the country’s mining sector.

While the traditional bastions of stability for Latin America’s mining investors are not yet crumbling, they appear to be joining their regional peers on the path of greater resource nationalism. Only time will tell how far each one goes down this road.