As the COVID-19 pandemic threatens the global economy, sovereign coping capabilities will be put to the test on multiple fronts. A growing number of states, including those in Latin America, have been forced to take an array of measures that are at odds with fundamental features of democracies, including:

- The formal declaration of the ‘state of exception’ – whereby governments limit civil liberties like freedom of movement and assembly for varying periods of time

- Threats to electoral timelines due to the logistical challenges resulting from the states of exception

While in some cases the effective management of the crisis will restore lost confidence in leaders, in most, we expect a resurgence in popular unrest once full democratic liberties are reinstated.

Social stagnation and unfulfilled promises

In Latin America, the significant spike in civil unrest experienced during 2019 appeared to set the region up for a volatile 2020; yet, the enforcement of social distancing will do away with such risks for now.

Polls show that social distancing measures enjoy sound levels of support across most jurisdictions, despite their negative economic impact. States will be able to cushion some of the pain, depending on their fiscal position. Yet, it is likely measures will need to be extended, increasing the probability of long-lasting economic stagnation that will challenge governments across the region.

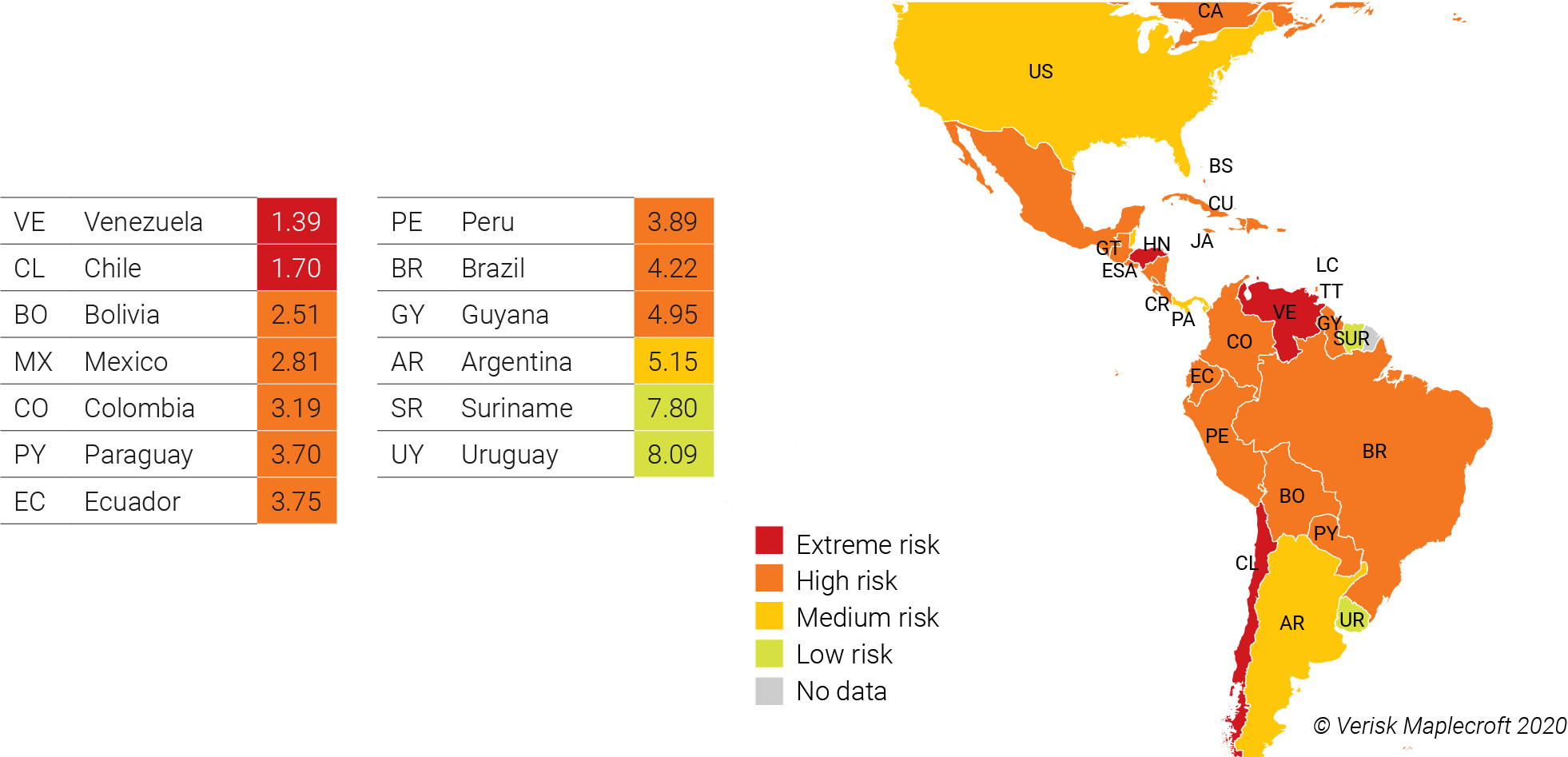

Most countries in Latin America that have declared comprehensive states of exception are also rated extreme or high risk in our Civil Unrest Index, including Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia.

If pandemic measures in these countries stem infection rates, the situation could improve and give back control of the political agenda to previously weakened administrations. But, if results do not materialise, healthcare systems collapse and harsh economic impacts are felt, discontent will spike, and the removal of social distancing measures will re-ignite social unrest. Countries like Venezuela - which has the worst performance in the Civil Unrest index in the region – will face a major risk of social breakdown.

‘Middle ground’ nations are also facing a ‘make or break’ moment. In the case of Chile, which saw the highest increase of civil unrest of any country in our global dataset in 2019, the effective handling of the crisis could give back to the Piñera administration some of the support lost last year.

Yet, there is a latent risk that the mishandling of key economic decisions during the lockdown – such as those to maintain income security and contain inequality - backfires and triggers a major backlash when the 90-day state of emergency lapses. Such a scenario would be disastrous for established political parties at the ballot box.

The ‘danger’ of elections

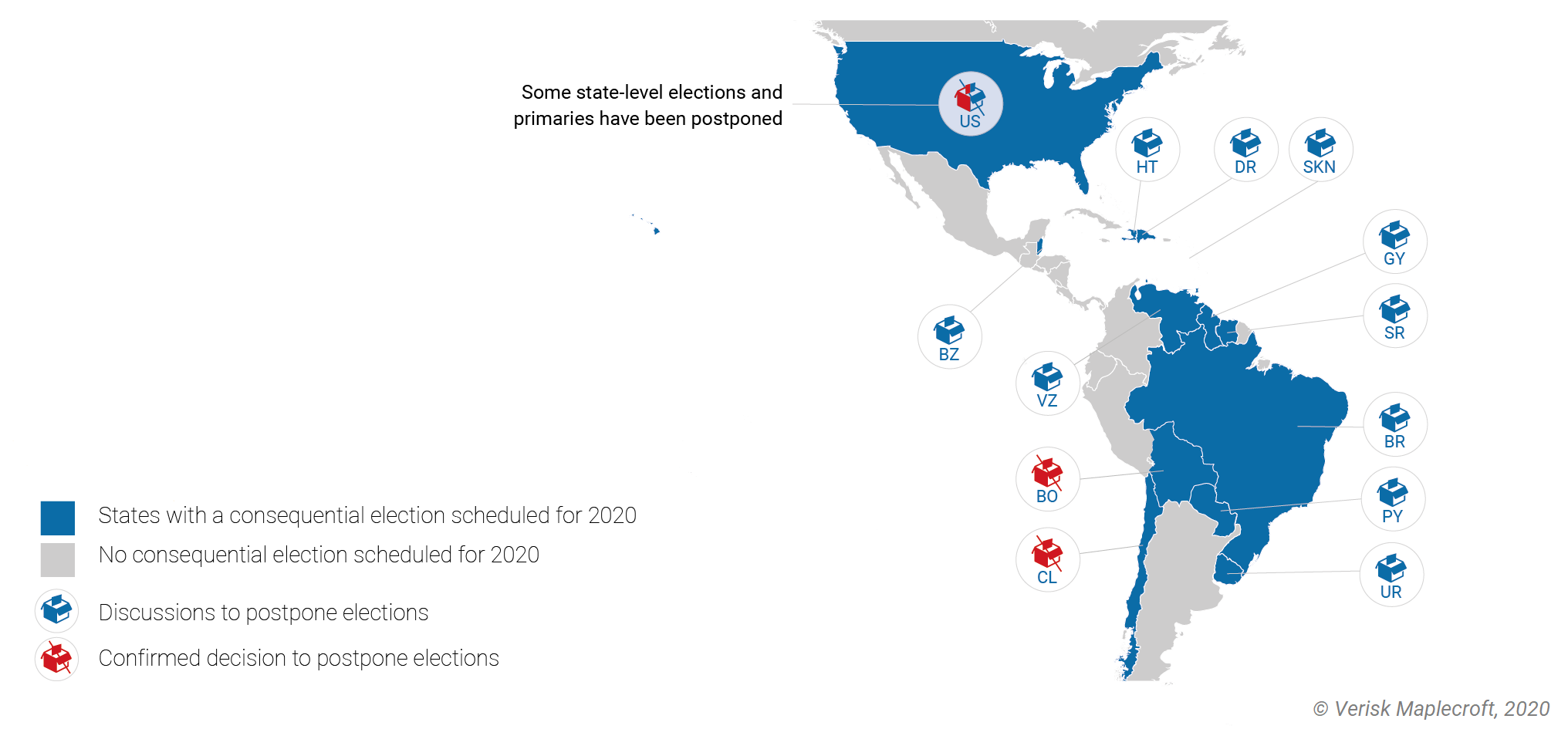

The need to contain COVID-19 could wreak havoc against one of the fundamental pillars of the democratic system – the ballot box. In the Americas, 15 countries are scheduled to have elections in the remainder of 2020 – ranging from national to municipal votes, and a constitutional reform referendum. While still too early to determine how many will be disrupted, in countries where support for the political class is in tatters, the pandemic is likely to further erode public perceptions of the effectiveness of democracy.

Bolivia and Chile are two examples of countries to watch closely. The former lacks government legitimacy since the 2019 general election results were declared fraudulent and former President Evo Morales fled into exile. The newly scheduled vote for 3 May has now been suspended, pending confirmation of a new date. Chile has also postponed the constitutional reform referendum, but unlike in Bolivia, the confirmation of the ballot for 25 October mitigates the government’s exposure to accusations of using the pandemic to undermine democratic institutions.

The legitimacy conveyed by strong levels of democratic governance (given by procedurally fair and timely elections) reduces the risk of political instability, increases transparency in government decision-making, and reduces uncertainty and reputational risk for investors.

Although we expect most governments to seek broad support to cope with the crisis amid unprecedented operational challenges - such as congresses working remotely, isolated from executive decisions - political polarisation is likely to add pressure to a bleak scenario. Such is the case for Brazil, where heated policy disagreements between federal and state authorities, as well as the executive and legislative, are taking place. While still far from gaining traction, threats of impeachment and of social mobilisation point to the possible risks to come.

Putting the lid back on the pressure cooker, threatens a bigger explosion

We consider a ‘return to normal’ in the region’s political landscape unlikely until - at least - 2020-Q4. As our Political Risk Outlook for 2020 showed, a quarter of countries experienced a dramatic surge in protests in 2019 and sent unprepared governments across all continents reeling. Prior to the pandemic, our data and projections pointed towards the continuation of turmoil in 2020, as the pent-up rage that boiled over into street protests had caught governments by surprise.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the lid back on the pressure cooker. The key variable to determine what happens once the containment measures are lifted is how efficient measures prove to be. Some governments could regain popular support and buy time to defuse discontent. However, with policymakers increasingly relying on a clampdown by security forces to enforce social distancing, governance systems will face unprecedented strain. In this context, a renewed surge in civil unrest in the aftermath of the pandemic is likely.