Latin America 2020: Aftershocks of civil unrest will continue

by Jimena Blanco,

Bouts of civil unrest are common in Latin America, but 2019 saw a serious bucking of the regional trend. At the onset of the year, nine of the region’s 10 largest economies sat in the extreme- or high-risk category of our Civil Unrest Index. The only outlier was Chile. Fast-forward a year and the country now joins Venezuela in the 10 highest risk locations globally for business disruption from large scale protests.

The wave of mass demonstrations that hit Santiago on 18 October 2019 – and then spread to most large urban centres–came as a bolt from the blue for those observing the country from afar. Chile’s posterchild image of open-market economic success, poverty reduction and institutional development – showing the path other Latin American economies should take to achieve developed status – is now on life support. So, how will the unrest impact the economy, and what should we expect in 2020?

A costly political transformation

Official estimates from the Ministry of Finance put the damage done by the protests at USD4.6 billion, slashing GDP growth from 3.2% to 1% in 2019. The sharp contraction in economic activity means that fiscal revenue will shrink by USD3 billion in 2020 – which is equal to the economic activity lost in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, the second largest ever recorded in Chile.

While the insurance sector has yet to release a consolidated cost arising from the protests, the damage suffered by major retail chains presupposes a high bill for the industry.

Chubb Ltd. reported USD353 million in losses as a result of unrest in Chile and Hong Kong in Q4 2019.

In this context, industry sources report that premiums have doubled and that due diligence required to price in potential losses from a recurrence of violent unrest is on the rise.

Economic trigger opened door to demands of institutional overhaul

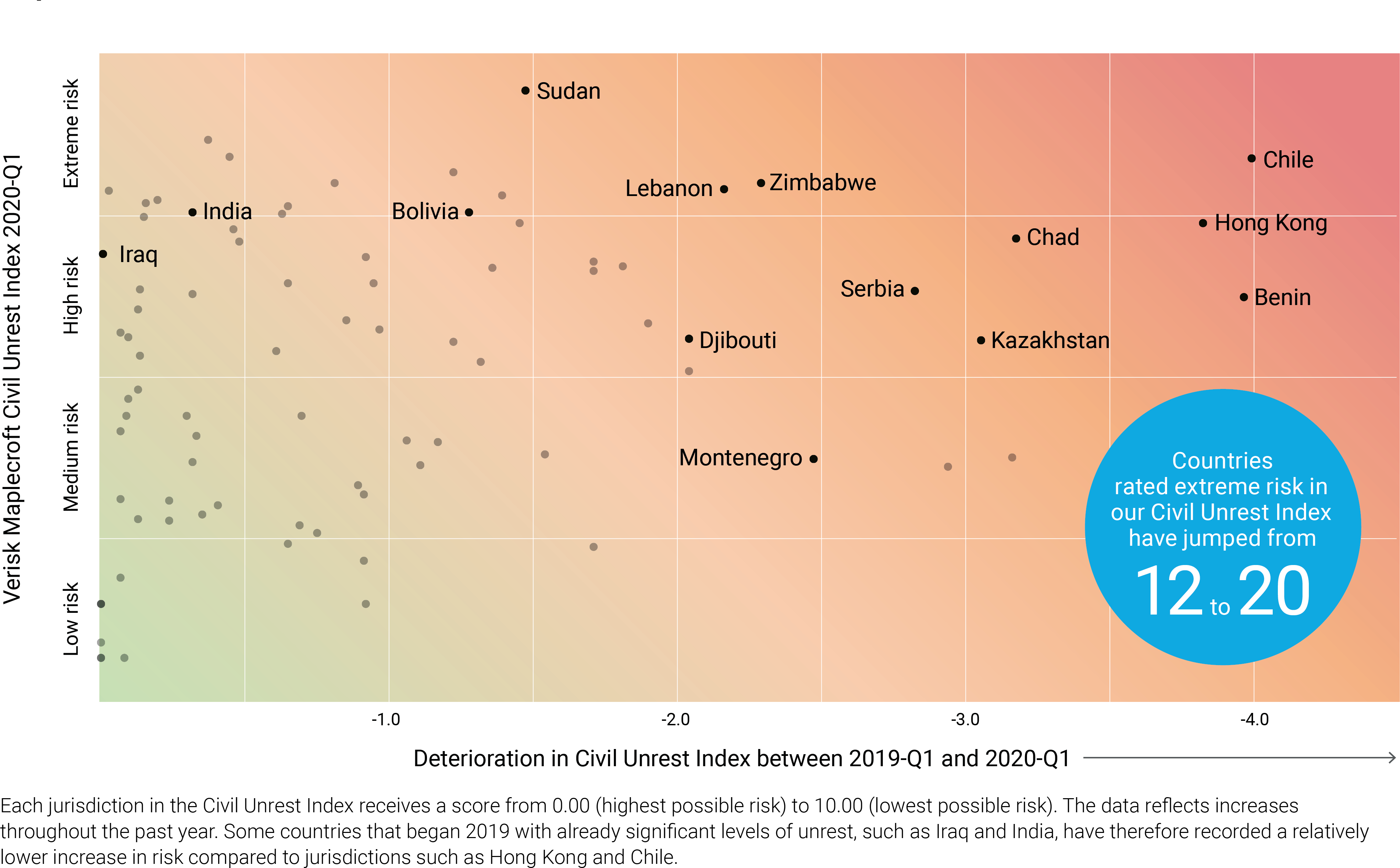

In our quarterly Civil Unrest Index, Chile posted the highest growth in risk between 2019-Q1 and 2020-Q1 than any other country. It went from ranking 91st globally to becoming the 6th riskiest place in terms of the exposure of business to disruption caused by the mobilisation of societal groups in response to economic, political or social factors. In terms of the severity and frequency of protests, Chile now sits alongside Hong Kong as the world’s riskiest location

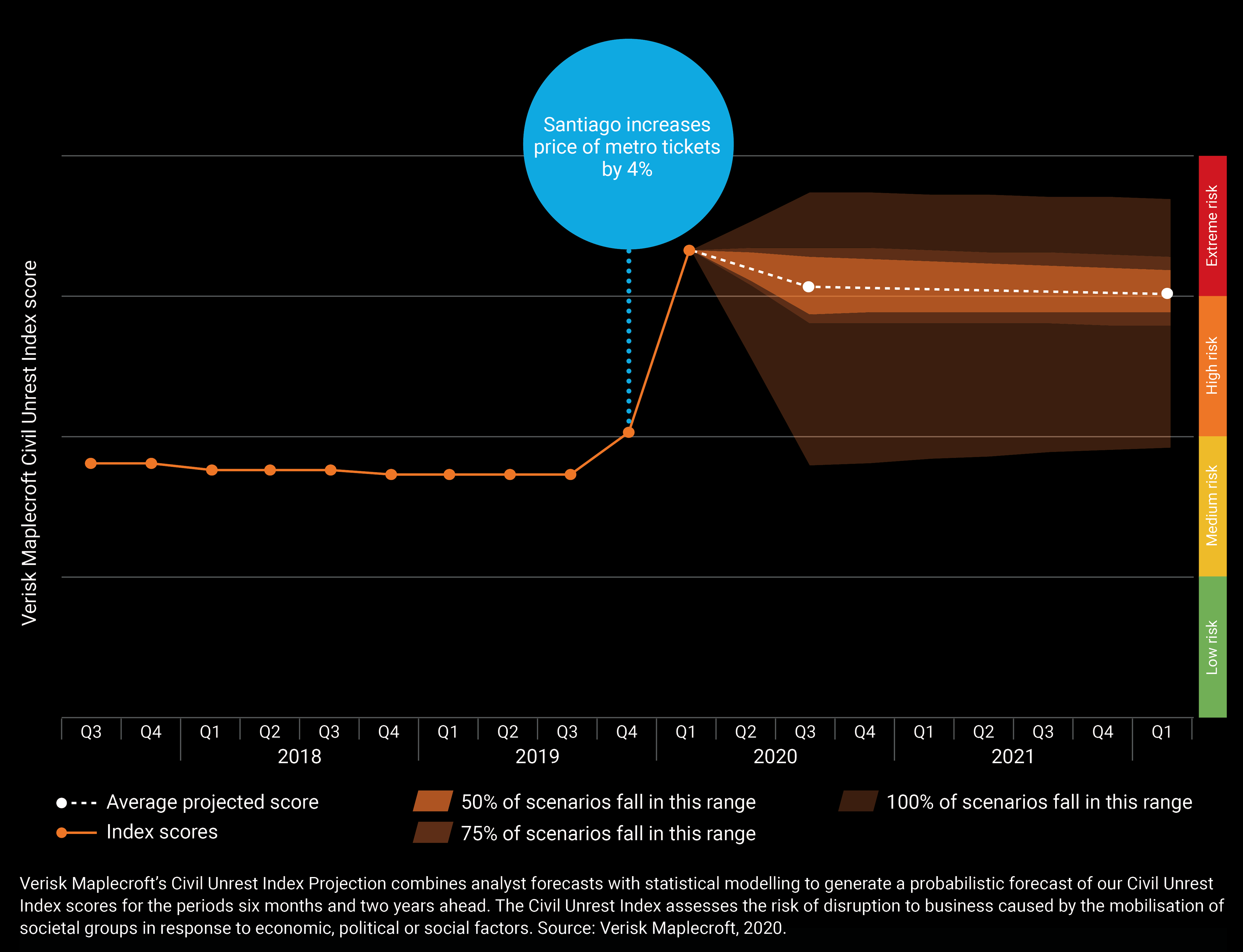

The signs that Chile could head into a period of heightened social tension were there – and, in fact, had been there for some time. Chile’s performance in our Civil Unrest Index had declined steadily since 2016-Q1. And in our Civil Disorder model, which generates an expected count of the number of violent protests or riots a country will experience during the next calendar year, Chile had sat in the extreme risk category since 2018-Q1.

The reasons for the surge in violent unrest are complex and diverse. In Chile, economic demands quickly escalated to encompass myriad claims that successive administrations had been unable to resolve since the student protests of 2011-13. Income inequality and high living costs made a seemingly trivial 30-peso (USD0.04) increase in the price of metro tickets in early October the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.

Indeed, analysis of our data suggests that a deterioration in some risk factors within the Civil Unrest Index gave an early warning sign. Subsidy cuts were the single biggest indicator that the risk of civil unrest was growing in Chile. Inflation was above the Central Bank target in 2014-2016, and the weakening of mechanisms that allow the channelling of discontent before it erupts into unrest also played a role.

What next?

The economic demands turned into political ones, which forced the government into the path of complete constitutional overhaul that will dominate in 2020. Our baseline forecast for Chile is a minor reduction in unrest over the next six months, while the country will remain in the extreme risk category until at least 2022-Q1 – although the projection allows for some uncertainty.

Our projection means that we do not expect the underlying causes of unrest to be resolved over the forecast period. The constitutional revision process is set to last from 2020 to 2023, and we expect spikes of unrest to continue during this period, particularly around key votes.

Furthermore, there is a risk that protestors will begin targeting specific industries – for example by blockading key arteries that provide access to mining operations – as a means of forcing the government’s hand into acceding to their demands. With official economic projections for 2020 at only 1.3% growth, sustained protests could send the country into a recession for the first time in a decade. This would increase fiscal pressure on the administration of President Sebastián Piñera, which could face higher outlays with falling resources.

Volatility in the region set to remain high

Regional governments should take heed of 2019’s experience. Latin America witnessed major outbreaks of civil unrest not only in Chile but also in Ecuador, Bolivia and Colombia. The latter two also saw their global ranks fall significantly, from 41st to 21st riskiest and 48th to 32nd riskiest countries respectively. And while individual triggers varied in these countries, all had experienced positive economic growth for most of the previous decade but failed to reduce the inequality gap.

It will take years to resolve the underlying causes of unrest in Chile and other countries in Latin America. In a region where overall economic growth continues to disappoint, getting the solution right in countries that have experienced positive economic performances is crucial to maintain openness for investment and trade.