Trade relations between China and Latin America have been transformed over the last 20 years, as the two regions have seen a mutual benefit in developing links – one as a route to global expansion, the other as a means to fund economic growth. Chinese interest in trade and M&A opportunities puts it in direct competition with traditional US investment in its own backyard, and can be leveraged in Beijing’s ongoing trade war with Washington.

As the US similarly seeks to pressure China through trade tariffs, and Beijing looks to expand its Belt and Road Initiative to secure crucial resources, Latin American countries are the focus of competing trade pressures and incentives from the two superpowers.

While some governments in the region have aligned themselves ideologically with one superpower over the other, most Latin American countries look pragmatically to balance their political interests with the need to develop long-term economic opportunities. It is also the case that Beijing is becoming more strategic in its investment priorities, with its global FDI falling for the second year running in 2018 (falling by 18% overall). This is owed partly to the reorientation of some Chinese transnational investment towards national priorities, and also partly to the trade disputes with the US and the EU.

In our view, Beijing’s interest in Latin America in 2020 will look to the following:

- An expansion of trade to absorb Latin American commodities ‘punished’ by US tariffs, and to support the replacement of US exports facing Beijing-imposed levies with cheaper Latin American alternatives.

- A gradual expansion in greenfield projects to reduce shipping costs to China and other nations along the Belt and Road Initiative.

- The potential for some renewed Chinese lending to cash-strapped regional economies, via existing or new financial mechanisms.

Register for our Political Risk Outlook 2020 webinar

China is diversifying its investment portfolio in Latin America to strengthen its supply chain

Beijing has a vested interest in defending and increasing its role in the region, particularly in terms of agricultural goods, as China looks to protect its food security. As of 2018-2019, 60% of China’s soya imports originated in Latin America. To date, almost 50% of Chinese FDI in Latin America has been heavily concentrated in extractives – less than 1% of its investment was destined for the agricultural sector between 2003 and 2016, for example – but latterly Chinese investment in the region has been diversifying to include, particularly, the agri-industry.

China has also moved to invest more widely in regional infrastructure, power generation and utilities and shipping.

With Chinese companies and consumers becoming more dependent on Latin American commodities and agricultural produce, it is in Beijing’s continued interest to reduce costs and secure supplies and transport.

In the early years, much of China’s investment in Latin America was in direct JVs with state-owned or state-controlled enterprises. But gradually it has extended to the private sector and is being channelled through M&As, thereby giving access not only to natural resources but also to energy generation, infrastructure and also to market position. According to the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, the top 20 M&A’s in Latin America in 2018 included Chinese acquisitions of a major electricity firm in Chile, Brazil‘s most profitable port company, and a water utility in São Paulo, for a combined total of USD3 billion.

Unlike in Africa, Chinese outlays in greenfield infrastructure projects previously represented less than 5% of its total investment in Latin America. This is now changing.

Again, this diversification is of mutual advantage to both the region and China. Higher costs and more complex ESG requirements threaten to deter Western lenders from embarking on mega transport infrastructure projects in the political tinderboxes of Latin America. In offering an alternative, China is positioned to secure key resources and boost its foothold in the region.

Download the Political Risk Outlook 2020

By and large, this comes at the expense of US economic interests, particularly in South America but also closer to home in Mexico. Thus, even as Washington puts pressure on friends and foes to address the US commercial imbalance with China, it may find that the opposite is the result.

A pertinent example is the Trump administration’s restoration of tariffs on Argentine and Brazilian steel and aluminium. This move is designed to force both countries into negotiations, with the US government wanting to improve the competitiveness of US soya exporters against Southern Cone producers. Yet, this may prove counterproductive for the US in global strategic terms.

What is the market impact?

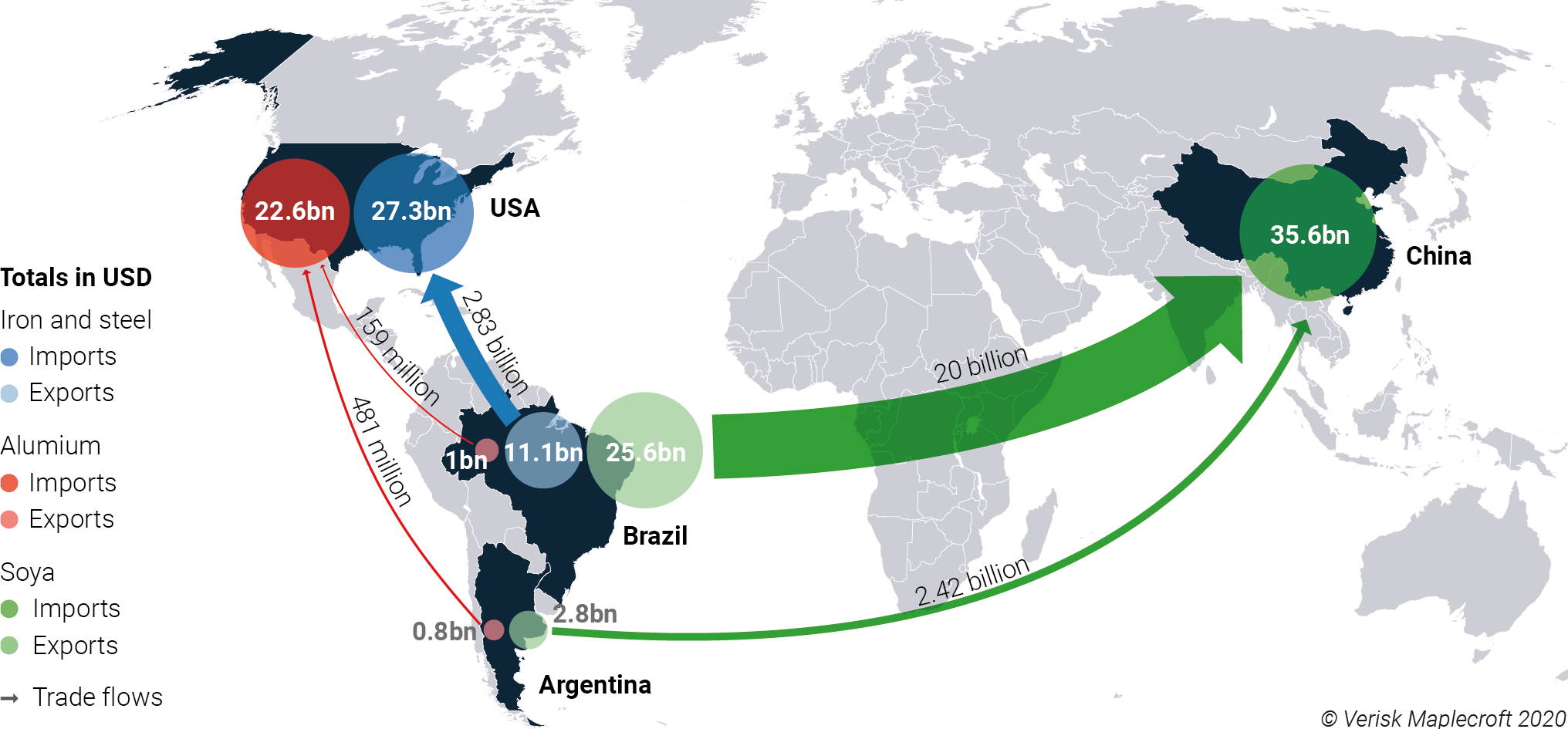

As Figure 1 shows, Argentina and Brazil’s aluminium and iron ore exports to the US, while considerable at USD3.47 billion, are only a fraction of their soya flows to China – USD22.42 billion. And while the aluminium and iron ore industries have deep pockets and strong political influence in their respective countries, the larger need to stabilise economic growth in Brazil – and avoid the economic abyss in Argentina – almost certainly will push the two governments closer to China, not Washington, regardless of their radically different political hues.

Likewise, as affordable external financing becomes increasingly challenging, China becomes a more appealing alternative to the US to bankroll deficits and capital investment needs in the region, particularly since Beijing’s ESG bar is considerably lower. That is not to say that China’s lending has no strings or conditions attached, but its T&C’s tend to be commodity export commitments rather than IMF-style structural policy demands.

While the Trump administration sees trade and financing negotiations as a zero-sum game, Latin American governments seeking to boost weak economic growth in 2020 will welcome interest from both superpowers. In our view, pragmatic economic need, rather than politics and ideology, will underpin Latin America’s deepening relationship with China in the coming decade.

What if…China bails out the battered Argentine economy?

Facing a 10th potential default, Argentina urgently needs to restructure its debt with the IMF and institutional lenders. The newly installed left-wing President Alberto Fernández has been keen to maintain a strong relationship with the US to secure its backing in negotiations with the IMF – in exchange, sources say that he has interceded with President Nicolás Maduro to secure better treatment for US business interests in Venezuela.

However, should Washington’s political demands regarding Venezuela threaten the cohesion of Fernández’s disparate Peronist coalition at home, or the IMF require the maintenance of austerity over a protracted period, we expect him to seek a lifeline elsewhere. With Venezuela itself in deep bankruptcy, it is not inconceivable that China could step into the breach.

A Chinese bailout – not dissimilar from Venezuela’s purchase of Argentine debt in 2006 – almost certainly would be in return for hydrocarbon export commitments from Argentina, plus Chinese financing of the infrastructure needed to secure the supply. With US majors among the top investors in Vaca Muerta, Argentina’s shale play may yet become a bargaining chip in the strategic face-off between the US and China.