Kibali ownership battle will rattle cobalt miners

by Indigo Ellis,

Key take-aways:

- The state remains power hungry, eager to eke out as much revenue as possible from the new mining code.

- The Congolese government is chipping away at companies’ profits and tightening ownership controls.

- There has been a significant increase in the risk of state resource nationalism targeting businesses in DR Congo over the past year.

Kinshasa’s ongoing drive to establish ever greater control over the country’s mineral resources is set to damage the long-term viability of cobalt mining. The state is clearly leading a charge to generate more revenue with the new mining code, but it is its increasing unreliability as an investment partner that is really making companies fearful.

Warning signs, such as the government’s attempt to block the transfer of ownership of Kibali mine, are raising the threat of legal arbitration against the state. Moreover, the one-year outlook is bleak, with December’s election unlikely to temper the government’s resource nationalist tendencies.

The government is chipping away at companies’ profits and tightening ownership controls in three main ways. First, the state is trying to seize private assets, as shown by its attempt to take control of Glencore’s Kamoto mine in June. Second, it is raising taxes, as seen with the hike in the royalty rate for strategic substances that is due to come into force at the end of October 2018. Third, the state is blocking a commercial transfer of assets at the Kibali gold mine.

Cobalt likely to feel state’s encroachment next

On 28 September, the minister of mines announced that the government was attempting to block the transfer of ownership of the Kibali gold mine to Barrick Gold after its takeover of Randgold Resources. The ministry is citing a clause in the new mining code that says the state must pre-approve all changes of ownership relating to mining titles. But the main reason the state is intervening is to have a pretext to squeeze more money out of the mining industry. It will likely seek a large financial settlement from both Barrick and Randgold to bolster government finances, as it did with Glencore in June 2018.

The government’s toughening stance is unlikely to remain confined to gold mining. Barrick and Randgold have only been targeted because they were the first companies to try and skirt the shareholder clause in the new mining code. The state’s decision to block the transfer raises major concerns for cobalt mining in DR Congo.

Firstly, mining companies’ negotiations with the government over the new mining code will be even more difficult than previously anticipated. By blocking the Kibali deal, the government has sent yet another sign that it is unwilling to compromise on the requirements of the new mining code. The chances of firms being able to negotiate individual ‘one-off’ deals with the government to limit the effect of the new requirements on their operations and their profits appear bleak. Indeed, companies in the MPI industry body believe the code is already being applied too strictly.

The state’s unwillingness to compromise will push mining companies towards initiating arbitration proceedings against the government to resolve disputes over the new code. These slow and costly arbitration processes will also delay operations, threatening global supply levels and rising cobalt prices. Moreover, a flurry of court cases would very likely deter new entrants, both those looking to develop fresh prospects as well as farming-in to existing mines.

Legal action also raises the spectre of state retribution. In two similar cases where companies were embroiled in litigation with the Congolese government, in 2010 and 2018, the state attempted to seize mines belonging to the claimants as retribution. In the Barrick-Randgold case, if the government pursues a retributive course of action, we would expect it to try to increase the state’s 10% share in the Kibali project, at the very least.

Finally, the government’s increasingly hard-line mining policies will make it more difficult for companies to secure the financing to start and expand cobalt mining projects. Any further deterioration of relations between mining companies and the government will intensify industry efforts to source cobalt from more stable and favourable operating environments.

The risk of resource nationalism is likely to remain extreme

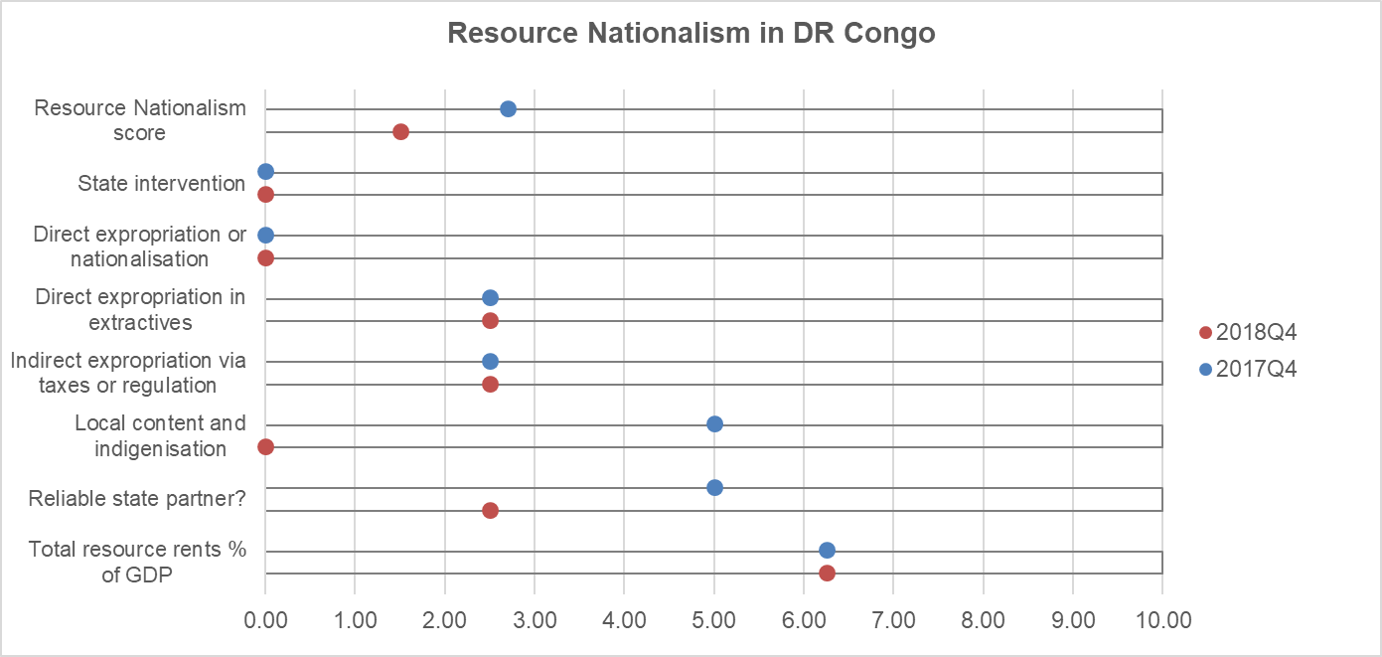

There has been a significant increase in the risk of state resource nationalism targeting businesses in DR Congo during the past year, as shown by our Resource Nationalism Index. Over the four quarters from 2017-Q4 to 2018-Q4, the score has dropped from the high-risk category to the extreme risk category (from 2.70 to 1.51). Moreover, it has dropped by an average of 0.60 points on our risk scale over the past two consecutive quarters.

The change has largely been driven by the indicator assessing state participation in resource extraction, which evaluates the reliability of the government as a partner. The increasing state encroachment over the past 12 months has undermined the state’s reliability as a partner. Both the introduction of more stringent regulations in the 2018 Mining Code and the government’s battle with Glencore’s subsidiary KCC over the operation of the Kamoto mine have dragged the score down.

We do not anticipate the situation to change radically over the next couple of months and so the risk of resource nationalism is almost certain to remain extreme for the next two quarters. If we take a slightly longer view, the effects of the new mining code will become even clearer by the time of the legislation’s first anniversary. Other factors will include how the Congolese authorities react to a potential international arbitration cases filed by mining companies against the government and the outcome of the Kibali ownership transfer. The current trend suggests that by 2019-Q3 the country’s score is more likely to have deteriorated further rather than have improved.

December’s election won’t alter the negative picture. We remain convinced that President Kabila’s chosen successor, Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, will win an unfair election and maintain the status quo in the mining sector. At least at first, Kabila will remain the puppet-master behind the scenes, ensuring state encroachment continues to increase. We therefore expect this downward trend to continue at least until the end of 2019 as the government seeks to extend its influence over all areas of mining.

The state remains power hungry, eager to eke out as much revenue as possible from the new mining code. The country’s slide towards extreme levels of resource nationalism, coupled with the prospect of numerous legal battles, is likely to dissuade existing investors from expanding projects and deter new entrants, even in cobalt mining.