Iran nuclear deal on its last legs

Uranium stockpiles rise above 300kg limit

by Torbjorn Soltvedt,

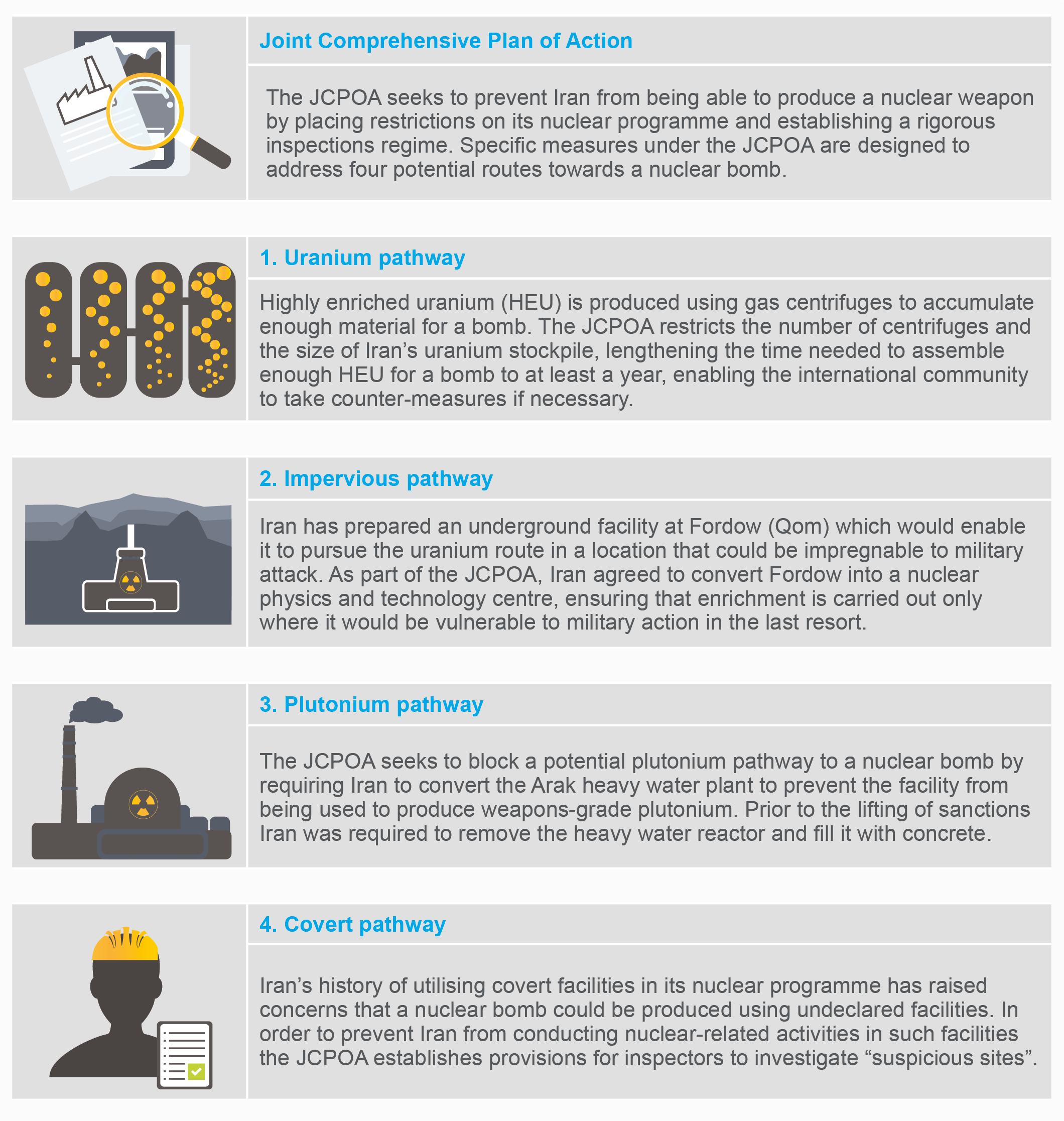

The gradual unravelling of the nuclear agreement between Iran and world powers is gathering pace. On 2 July, Iran confirmed that its uranium stockpiles had risen above the 300kg limit imposed by the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Less than a week later, Iran announced that it had enriched uranium above the 3.67% limit established under the agreement.

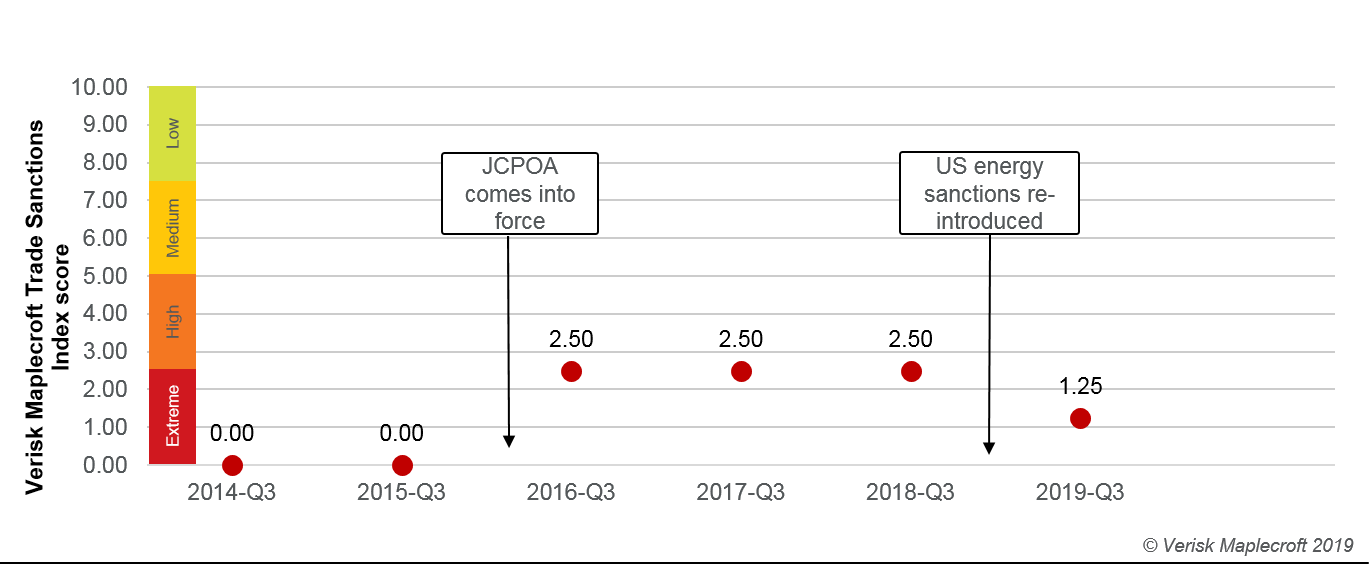

The JCPOA has been on borrowed time over the last two years at least. But with tightening US sanctions and the EU unable to normalise trade with Iran, Tehran’s latest move to push the boundaries of the agreement is likely to be the beginning of the end for the 2015 nuclear deal. Iranian non-compliance with parts of the agreement will also inevitably cause even greater friction with Washington at a time when regional tensions are already at a critical level.

JCPOA unable to deliver a significant economic dividend for Iran

Two key factors have contributed to the JCPOA’s failure to deliver as intended. Firstly, the agreement was always closer to a political commitment between the parties than a treaty in the traditional sense. As we cautioned in January 2017, due to the JCPOA’s reliance on temporary suspensions of sanctions, waivers and other workarounds, it very much depends on the support of the American president to function as envisioned by its architects.

Since assuming office in January 2017, US President Donald Trump has placed Iran under much greater pressure, culminating in the withdrawal from the agreement in May 2018, the re-imposition of US energy sanctions in November 2018, and the ending of oil import waivers in May 2019.

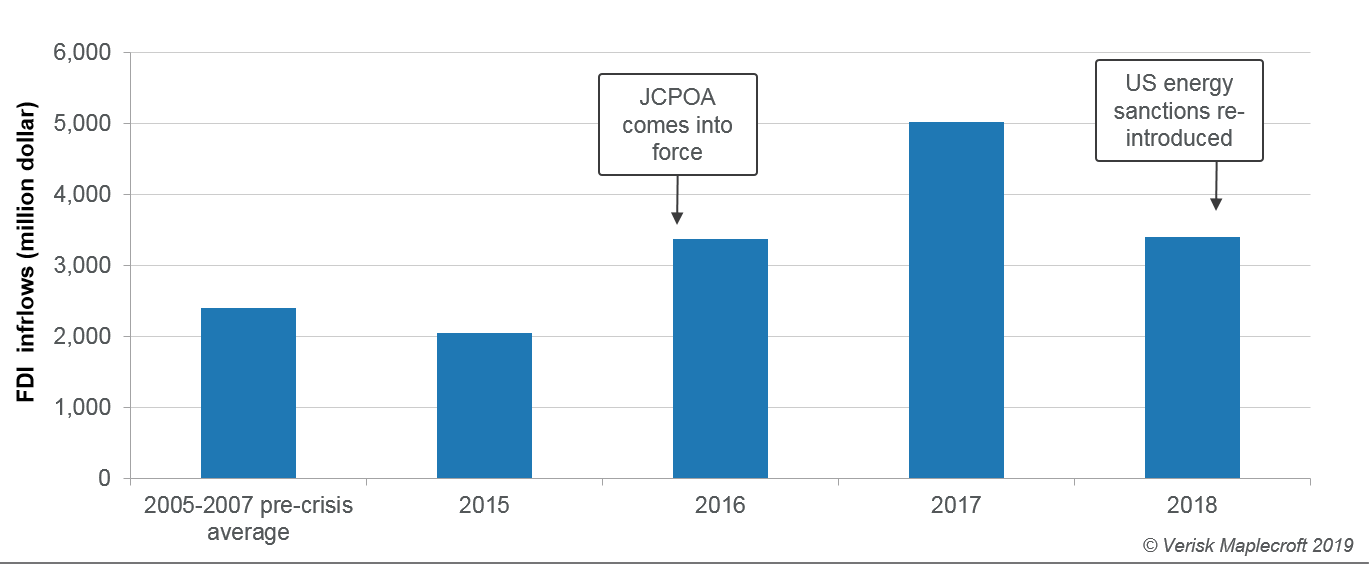

The second key factor behind the JCPOA’s unravelling is the lack of foreign investment since the conclusion of the agreement. As the figure below shows, the agreement has fallen far short of the Rouhani government’s expectations of a significant opening of the Iranian economy to foreign investors. In the oil and gas sector alone, Iran has sought up to USD200 billion in investments to realise the sector’s full potential.

The US withdrawal from the agreement in May 2018 effectively killed the agreement, but even prior to this most investors were hesitant to enter Iran. Most importantly, the JCPOA only focuses on nuclear-related issues and has not lifted a broad range of US sanctions relating to other issues such as Iran’s sponsoring of terrorism groups, the country’s ballistic missile programme or human rights abuses.

Given the Revolutionary Guards’ strong footprint in the Iranian economy, foreign companies have faced a substantial compliance burden and a high risk of violating US extraterritorial sanctions. Other than notable exceptions such as Total – who only pulled the plug in August 2018 ahead of looming US energy sanctions – most foreign companies felt that the risks outweighed the potential rewards even before the Trump administration’s decision to leave the JCPOA.

European Union unable to normalise trade with Iran

Iran’s recent decision to renege on some of its commitments under the JCPOA and threats to further lower its compliance is a last-ditch effort to spur the remaining JCPOA parties into action. But Iranian hopes that the remaining parties to the JCPOA could blunt the impact of US sanctions and keep Iran open for business were always unlikely to be met.

Small, independent European companies with no exposure to the US financial system could benefit from the EU’s INSTEX trade mechanism which became operational in June 2019. Larger companies, however – many of which have US shareholders or raise finance in the US – are very unlikely to risk doing business in Iran. Beyond Europe, it is also clear that Chinese companies are taking US sanctions on Iran seriously. CNPC’s request in early July 2019 to suspend its South Pars Phase 11 contract for two years due to US sanctions is further evidence that Washington’s hardening Iran stance is enough to deter the vast majority of international oil and gas companies.

What Iran ultimately wants, normalised trade relations with the EU, will not happen as long as the US maintains the current level of sanctions against Iran and while the US-blacklisted Revolutionary Guard remains a dominant actor in the Iranian economy. The EU can encourage European companies to do business with Iran and enable transactions to be carried out. But ultimately, it is the companies themselves that bear the risk of falling foul of US sanctions.

Iran will likely respond to US pressure with lower compliance and covert military action

Even minor Iranian violations of the JCPOA open up a new fault line with the US and risk accelerating the agreement’s demise. Iranian instances of non-compliance will only add fuel to calls for an even broader and tighter sanctions regime from Iran-hawks in the Trump administration. Additionally, the limited mechanisms established by the EU for trade with Iran are conditional on Iranian compliance with the JCPOA. Although such mechanisms have made little material difference to Iran, their removal in the event of sustained Iranian non-compliance would be the final nail in the JCPOA’s coffin.

It is also likely that Iran will respond with covert action in parallel with ongoing steps to downgrade its compliance with the JCPOA. In June, we explained why Iran stands out as the most probable culprit of several tanker attacks in recent months. With Iran hawks in the Trump administration aiming to push Iranian oil exports below 500,000 barrels per day, the risk of further incidents in the Gulf of Oman, Persian Gulf and broader region is high. If Iran seeks to retaliate against tightening sanctions – especially those targeted at oil and petrochemicals exports – covert action is most likely to take the form of attacks against tankers and oil and gas infrastructure in Saudi Arabia or other Sunni Gulf states.