Investing in Indonesia’s new capital may come with a reputational cost

by Olivia Dobson,

A relocation of Indonesia’s administrative capital to a brand-new city in East Kalimantan on the island of Borneo has been proposed to reduce pressure on the current home of government, Jakarta, a city plagued by poor air quality, traffic gridlock and flooding. But will the Jokowi administration simply swap one set of risks for another? The ecological impacts of building a new city, pressures on natural resources and the relocation of indigenous groups could all set alarm bells ringing for investors.

Here, we examine some of the risks and opportunities that could shape the success of this new development, alongside the implications for investors and operators.

Impacts on sensitive habitats could draw international criticism

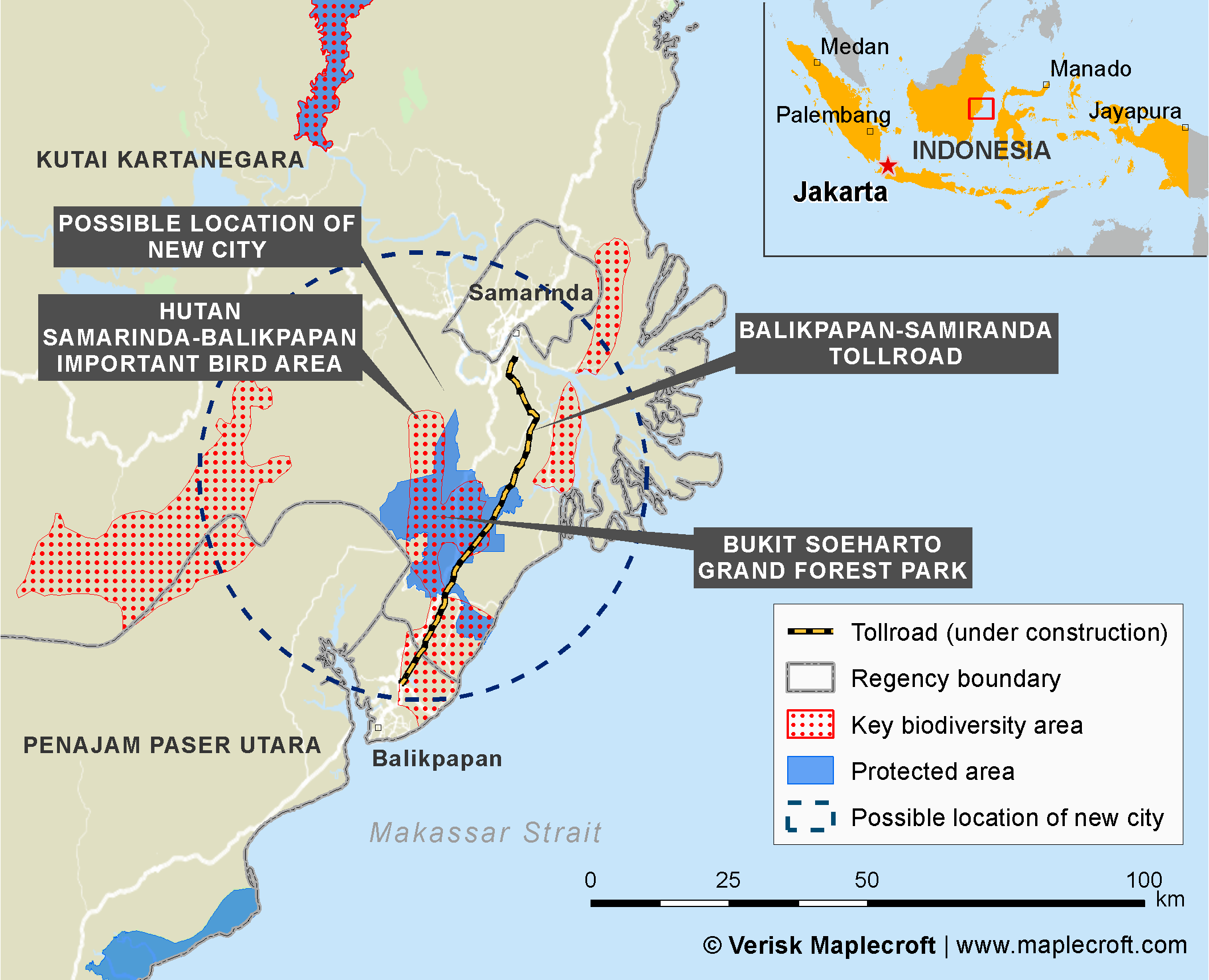

East Kalimantan has extremely rich biodiversity, including rare species such as orangutans, which will place investors in the construction of the new city under intense scrutiny from NGOs and the media. The two regencies (administrative divisions) where the new city is to be built are both rated ‘high risk’ in our Biodiversity and Protected Areas (Terrestrial) Index, indicating the value of the species and environment located there.

Reports show the new city will be built partly within the protected Bukit Soeharto Grand Forest Park. This area has already suffered significant degradation through logging, mining and agribusiness, while a new toll road has split existing habitats. Investors should be prepared that any major development will likely attract criticism for further ecological impact – actual or perceived. The government’s vision to construct a ‘green’ city does include habitat restoration objectives, but there is still a risk that negative perceptions of the city construction could leave project investors exposed to reputational damage if not managed responsibly.

New city will raise pressures on water resources

While drier than other parts of Indonesia, Kalimantan experiences year-round rainfall with two distinct wet seasons. Data from the World Resources Institute indicates that total water withdrawals account for less than 1.0% of available water in the watershed where the new city would be located. In contrast, withdrawals in Jakarta exceed 95% of total available water. But historical data suggests the region is highly susceptible to periods of drought, so the increased pressure on available water resources may create conflict with other water users, including indigenous groups and farming.

Any water pollution from the new capital could also threaten the health of the Mahakam River and delta, which has importance to the aquaculture industry. The river already suffers from high levels of heavy metals due to mining activities upstream.

Environmental and social impact assessments liable to be fast tracked

Local news providers report that a strategic environmental assessment for the new city is expected as soon as November 2019. A full environmental impact assessment is expected to follow, but there will be concerns from environmentalists and human rights advocates that the accelerated timeline – 2024 has been mooted as a target date for the first occupants to move into the city – will see corners cut in the process.

Human rights groups claim that the construction of the new city would result in the forced displacement of the indigenous Dayaks and their livelihoods. Traditional lands in Kalimantan are already under threat from mining and agribusiness developments such as timber, rubber and palm oil plantations. Plans for the new capital will likely exacerbate land and indigenous rights violations and spark intense community opposition.

Water management key to avoiding natural hazard disruption

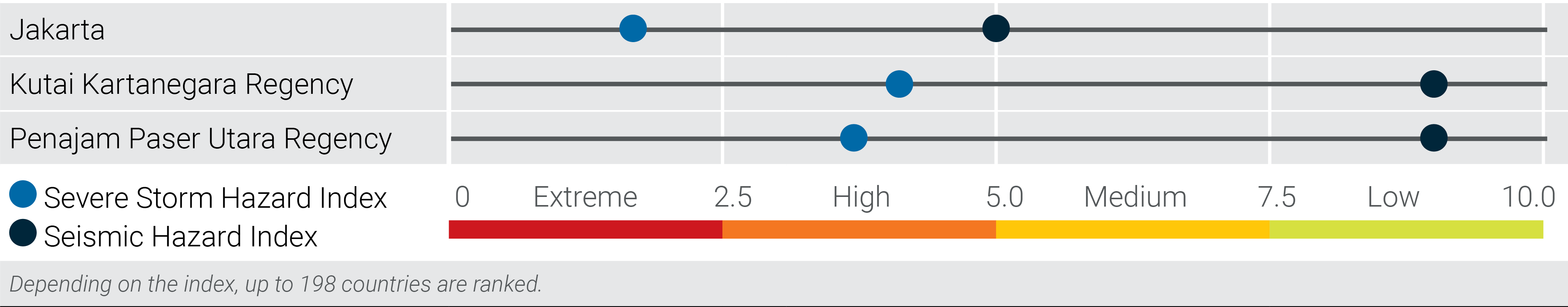

A key driver for relocating government functions from Java is to reduce exposure to natural hazards. The selected regencies in East Kalimantan do indeed have a far lower exposure to seismic hazards (see figure below), but they are still categorised as ‘high risk’ for severe storms. This will pose a challenge for the new city, which could see surface water flooding from intense rainfall events.

The impacts of recurring flooding experienced in Jakarta exemplify why managing water will be key to minimising this as a source of disruption for businesses in the new city. In addition to future-proofed stormwater systems to account for the impacts of climate change, this will require adequate waste management to avoid clogged drainage routes, along with strictly enforced zoning controls for building.

Private sector a key influencer

With the government planning to source 81% of the funding required to build the new capital from the private sector and public-private partnerships, investor due diligence will be an important source of oversight.

Outcomes will depend on the extent to which this group requires adherence to strict standards and best practice in the new city’s design, assessment, construction and operation. This degree of influence presents a considerable opportunity for business to drive positive results, but also to be the recipients of criticism and reputational harm if things go wrong.

No quick fixes

Pressures in Jakarta will remain the norm and the new capital will not address the vulnerabilities of the current capital’s urban environment. Companies will continue to experience disruption and infrastructure shortcomings and investments will remain exposed to natural hazards. Although interventions to tackle some of the city’s problems are beginning to materialise, the lead times and costs hamper resilience building.

The high-profile nature of both the proposal and Borneo’s ecological status will mean equally high stakes for those involved in the construction of Indonesia’s new capital. While the move presents the opportunity to construct a showcase sustainable city incorporating the last 30 years of learning in urban resilience, the proof will be in the pudding. Whatever its potential, investors will need to maintain pressure and scrutiny throughout the process otherwise they are likely to end up paying the price.