India, South Africa, Brazil face bleakest road to economic recovery among G20

by David Wille and Joshua Cartwright,

The world’s wealthiest countries are in for a rough ride as they attempt to bounce back from the economic enormity of the coronavirus pandemic. But India, South Africa and Brazil will experience the harshest repercussions, according to new research assessing the ability of G20 nations to recover from the unprecedented economic and public health crises.

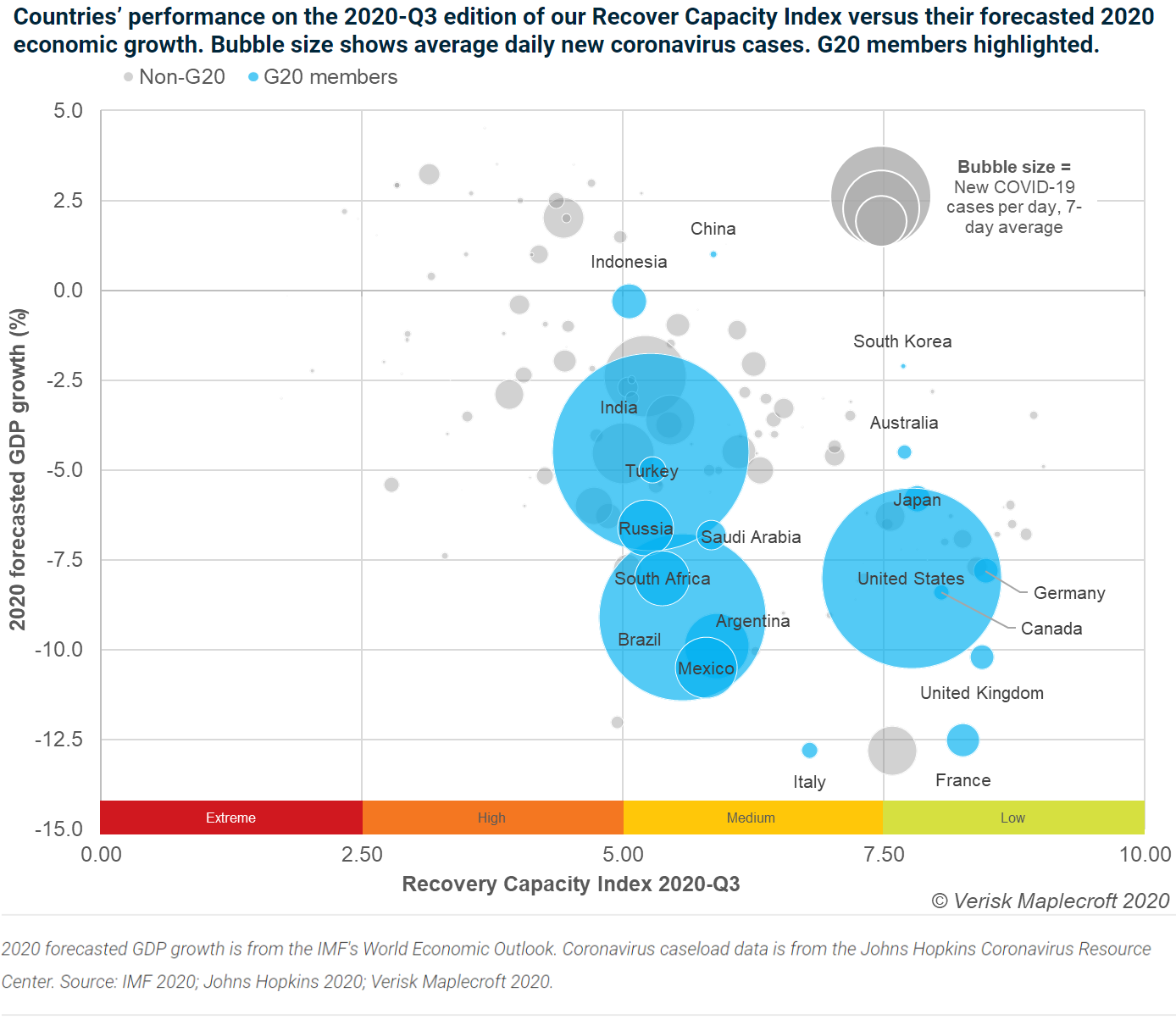

Verisk Maplecroft’s Recovery Capacity Index, which measures more than a dozen factors that underpin, or undermine, a recovery from the crisis, suggests members of the G20 will experience a two-track recovery. Western European and East Asian members of the G20 – initially hit the hardest by the pandemic – have the building blocks in place to recover much quicker than their emerging market counterparts.

The prospects are bleak for those countries now forming the epicentre of COVID-19 transmissions, particularly India, Brazil and South Africa. Of the G20 bloc, these three countries are among the bottom performers on our Recovery Capacity Index. And as the IMF forecasts that these three economies will shrink an average of 7% in 2020, a devastating setback, they are set to struggle with the aftermath of COVID-19 long after their wealthier peers have moved on.

These three countries are critical actors on the global economic stage, representing more than 10% of global GDP, 3.7% of total trade, 3.2% of direct investment flows and 20% of world population. A drawn-out recovery for these markets will have severe repercussions for the investment community, consumer markets and multinationals.

Interested in learning more? Don't miss the next webcast in our Coronavirus Series:

Which G20 members face the toughest post-pandemic recoveries?Governance poses the highest barrier to recovery

Western European and East Asian members overwhelmingly perform better on each element of recovery capacity captured in our index – scoring more than 40% higher on average than G20 members in emerging markets.

The largest difference between richer and poorer G20 members is the hurdle posed by weak institutions, especially high levels of corruption. South Africa, India and Brazil each score as ‘high’ risk for corruption in our dataset, with Russia, Mexico and Indonesia falling into or near the ‘extreme’ risk category. Corrupt, ineffective and unstable governments will be limited in their ability to direct funding to where it is most needed, failing to revive the economy even after the immediate crisis is dealt with.

Large exposure gaps also exist between G20 members in terms of their population sensitivity, which reduces a country’s ability to recover from even comparatively mild shocks. India, South Africa and Brazil are among the bottom performers in this pillar of our Recovery Capacity Index, reflecting a combination of high levels of poverty and low human capital.

India, along with Indonesia, scores as ‘high’ risk on the connectivity pillar of our Recovery Capacity Index, which measures the physical distance between populations and the presence of digital infrastructure that will dictate the speed with which workers and consumers can resume normal commercial activity. South Africa, China, Mexico and Brazil all score as ‘medium’ risk on the connectivity pillar of our index.

The Recovery Capacity dataset also emphasizes the role that compounding factors – the man-made or natural challenges that these countries grapple with alongside the pandemic – will play in hindering these countries’ recoveries. For Brazil, India and South Africa, disruption from civil unrest represents the largest compounding risk factor in our dataset.

The worst not yet over for G20’s least-resilient markets

In general, the more affluent G20 bloc members were quick to adopt strict societal lockdowns in response to the pandemic. Combined with their high fiscal flexibility, those in North America and Western Europe were able to support citizens as their economies entered a self-induced coma. Others, especially in East Asia, implemented effective testing and contact tracing regimes.

The clear outlier is the United States, which has had the least effective pandemic response of any developed market due to its inconsistent and politicised state-level reopening. An elevated coronavirus caseload will prolong the US economic downturn, but its high fiscal firepower and underlying resilience will enable the economy to bounce back once outbreaks subside or a vaccine becomes widely available.

In contrast, lower-income G20 countries have faced a grim catch-22. India and South Africa initially imposed strict lockdowns that they were later forced to relax due to the social spending required to support their populations and businesses, which maxed out their fiscal and budgetary capacity. But facing high virus caseloads, both governments have been forced to re-impose and sustain restrictions on the hardest-hit areas that will further hamstring their already decimated economies.

Learn more about our Country Risk Intelligence

Brazil failed to enact any widespread social distancing measures and is now experiencing the world’s second-highest daily virus caseload. After facing political backlash following unsuccessful state-level lockdowns, we expect Brazil’s governors to keep their economies open through the worst of the pandemic, which will impart a severe human toll on top of the economic impact.

Secondary risks also have the potential to upset what fragile recoveries these markets can muster. Civil unrest is projected to spiral, with the highest probability of deterioration among these economies expected in Brazil over the next six months, according to our Civil Unrest Index Projections dataset. The human and economic costs of the pandemic, combined with popular outrage over corruption allegations, are likely to mobilise protesters against Brazil’s leaders. That said, we expect Brazil to avoid the level of destructive civil unrest seen in nearby Venezuela and Chile. India and South Africa already score at or near ‘extreme’ risk for civil unrest.

These compounding factors will exacerbate pre-existing socioeconomic issues, rising unemployment and unsatisfactory government responses to the pandemic. This creates higher levels of uncertainty for investors, and large-scale civil unrest has the potential to derail even the strongest of economic recoveries. But even if they manage to avoid the worst, our Recovery Capacity Index suggests that India, South Africa and Brazil still have a long road ahead.